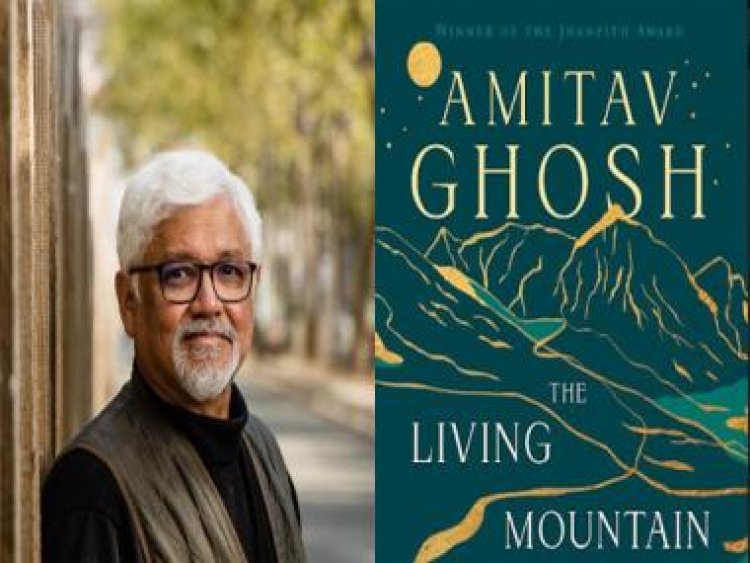

Amitav Ghosh unpacks colonization and global warming in The Living Mountain

Amitav Ghosh unpacks colonization and global warming in The Living Mountain

Author Amitav Ghosh must be lauded for the consistency with which he writes about global warming as a moral predicament, not only an ecological one. After books like The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016), Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sundarban (2021), and The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (2021), which dive into this subject, he is back with The Living Mountain: A Fable for Our Times (2022).

The fable as a literary genre is an inspired choice for a period in human history where the literal is valorized over the metaphorical, and the imaginative is snubbed in favour of the hyper-rational. Unlike the Jataka Tales, the Panchatantra, and Aesop’s Fables, Ghosh’s fictional universe has no animals or birds. What he does have at the heart of his book is a “living mountain” called the Mahaparbat, which is a source of sustenance for indigenous people. The mountain gives them food and medicine. They worship it with song and dance.

Their story is narrated by a woman named Maansi who loves reading. Having grown up in Nepal, she now lives in New York. She works as a sales manager for a line of designer clothing called Anthropologaia. Her company has chosen “Anthropocene” as the fashion theme of the year. The story appears to her in a dream that is more of a nightmare. It is about the impoverished inhabitants of a remote valley who suffer a terrible fate. Maansi is so overwhelmed by their suffering that she needs to meet her therapist to process her response.

When the therapist advises Maansi to write it all down, she accepts the suggestion. However, she does not stop at this. She wants to share her writing with someone that she trusts, so she reaches out to a person she knows from being part of an online book club. The identity of this person is never revealed, so we do not know if this happens to be Ghosh or someone else.

In the dream, Maansi visualizes herself as a young girl being raised in a valley that is home to “a cluster of warring villages”. While they spend a lot of time and energy fighting with each other, what they have in common is their reverence for Mahaparbat. They are taught by their ancestors to treat this snow-clad mountain as sacred, to honour it but to never step on it. They are not being superstitious. They appreciate how the mountain meets their economic and spiritual needs. Every year, when the snow retreats, Elders from these villages gather nuts, mushrooms, honey and herbs from the mountain and sell these goods to visiting merchants.

A compelling story usually has a conflict that needs to be resolved, and Ghosh’s book is no different. Trouble begins to brew when the villagers run into a stranger who is excessively interested in their mountain. He is upset about not being allowed to access it directly but he extracts answers to all his questions, and he takes copious notes when the Elders speak. Ghosh, who has a Ph.D. in social anthropology, acknowledges the colonial origins of his discipline. The stranger in Maansi’s story reminds us of the earliest anthropologists who were complicit in knowledge production that was used to justify colonial rule across the world.

The sanctity of the mountain is eroded when an army of Anthropoi show up in the villages. They see it as a resource to mined and plundered. They have no emotional bond with it. They believe that the villagers are letting all the riches of the mountain go to waste. This extractive mindset points to the relationship between colonization and capitalism. Since the Anthropoi have no respect or gratitude for the mountain, they do not see it is a living presence. They take from the mountain but do nothing to replenish it. They have to pay for this imbalance.

Read the book to find out what happens. Some readers might draw parallels with British rule in India, especially because we have grown up reading about how the British took raw materials from India to fund technological advancement and economic prosperity in their own country. Other readers might think more locally, and ponder over what happens when tourists throng to places like Himachal, Uttarakhand, Goa, and Kashmir. While tourism brings in revenue, one cannot overlook the environmental impact especially when a huge amount of waste is generated and tourists do not respect local cultures and ecosystems.

Published by Fourth Estate and illustrated by Devangana Dash, this book is also about the place of faith in our lives. It invites us to think about what we lose when we think of ourselves as separate from nature. Why do human beings think of themselves as superior to all other species? Is the ability to control, manipulate and exploit evidence of superiority? Shouldn’t we be more invested in cultivating the power of compassion? If we are more powerful, do we not have a responsibility to care about species that we share this planet with?

The book does not equate faith with a belief in a supernatural being sitting in a surveillance tower. The villagers are indigenous people. Their understanding of the sacred is immediate, tactile and creative. Through this book, Ghosh points out how the history of colonization is also bound up with the history of missionary activity that degrades indigenous cultural practices, plays the game of divide and rule, and disconnects people from their environment. It needs to be read widely, especially as it delivers a powerful message in less than 50 pages.

Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, journalist and educator who tweets @chintanwriting

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?