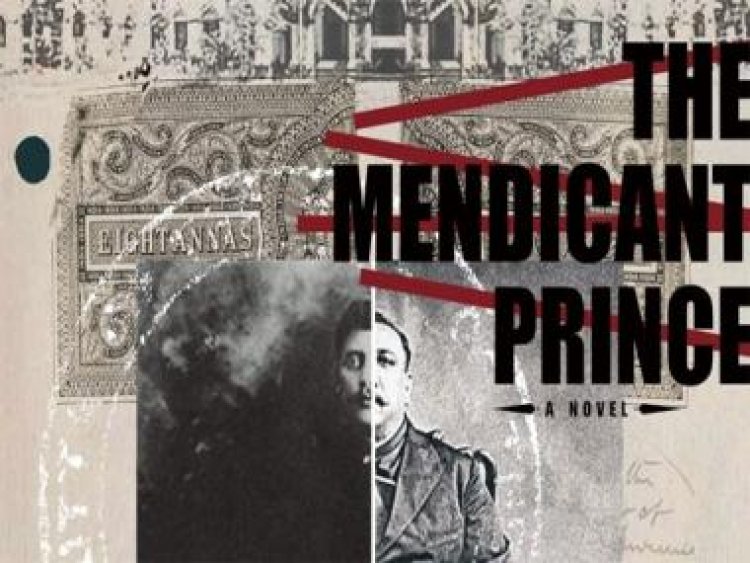

Aruna Chakravarti's The Mendicant Prince: A meticulously constructed work of historical fiction

Aruna Chakravarti's The Mendicant Prince: A meticulously constructed work of historical fiction

Ramendranarayan Roy, the second prince (mejo kumar) of the erstwhile Bhawal zamindari in modern-day Bangladesh, took a vacation for his deteriorating health in 1909. The syphilis-riddled boils on his back and legs were beginning to heal in the clean air and salubrious climes of Darjeeling when he suddenly worsened and died, leaving behind a young widow and a large family which would then get embroiled in a bitter succession conflict. 12 years later, a sanyasi or mendicant appears in Bhawal, bearing more than a passing resemblance to the long-lost prince which leads to a separate, even more protracted legal battle between agents of the crown (who were looking to add Bhawal to their list of conquests) and members of Ramendranarayan’s family who insisted that this sanyasi was indeed their long-lost mejo kumar.

Aruna Chakravarti’s new novel The Mendicant Prince (Pan Macmillan India) is a meticulously constructed work of historical fiction that reimagines the several intriguing characters embroiled in this age-old mystery and court battle — the would-be mejo kumar himself, Ramendranarayan’s wife/widow Bibhavati, mistress Elokeshi, elder brother Ranendranarayan, eldest sister Indumayi, second sister Jyotirmayi and many, many others. Chakravarti has previously won a Sahitya Akademi for her translation of Sarat Chandra Chatterjee’s novel Srikanta. Jorasanko, her earlier work of historical fiction, focused on the lives of the women of the Tagore household.

The Mendicant Prince telegraphs its ambitions fairly early on, when we realize how quickly the chapters change point of view—Chakravarti has taken on a dazzling range of voices here, including many of the aforementioned members of the Roy household, as well as other ‘onlookers’ to the mystery, stakeholders like the merchants of Bhawal as well as British officers who are more than a little puzzled at the sequence of events. With every new point of view, Chakravarti tells us some new and startling detail that adds to the mystery and/or the many superb character studies unfolding before our eyes. For example, take this passage, where Ramendranarayan’s wife Bibhavati is weak, anaemic due to lack of food, and borderline delirious due to trauma following her husband’s death. And then, after a few days on her own, she is visited by her sisters-in-law, whom she faces as a widow for the first time. It’s a powerful, dramatic scene and one that benefits from the degree of sensory detail Chakravarti piles on.

“Her thaan was crumpled and there wasn’t a single speech of gold on her person. Her lips seemed coated with wax and strands of long, tangled hair were spread out on the pillow. The two women, suddenly conscious of the rich saris and jewels that they wore and of the sumptuous meal they had just eaten, pulled their aanchals closer and tried to hide the gold boxes full of paan cones they carried in their hands. But they couldn’t hide their faces, sleek and shining with sugar and oil, and mouths crimson with paan juice and smelling of aromatic tobacco.”

And these same carefully fleshed out sensory details assume even greater appearance when the titular mendicant, the one claiming to be the mejo kumar, arrives. When his sister Indumayi invites the mendicant for a feast at her bungalow, she starts attributing meaning and proof to every single gesture of his, everything he chooses to eat

or not.

“I noticed that he hadn’t touched the steamed ilish with mustard and chilli paste. He had emptied the bowl of muitha on his thala. Muitha was our local delicacy made from the scraped flesh of the silvery chital that swam in shoals over the Ganga. My heart missed a beat. Mejo loved muitha! But a moment later another thought struck me. The man was not a Bengali. He was, quite naturally, nervous about tackling fish bones which could stick in his throat and cause acute pain and discomfort. Muitha was a dish of boneless fish balls cooked into a delicious curry with a variety of spices.”

The bare bones of the case

In the introduction to A Mendicant Prince, Chakravarti acknowledges the role played by the political scientist and anthropologist Partha Chatterjee’s 2002 book A Princely Impostor? The Strange and Universal History of the Kumar of Bhawal. Most of the factual details presented in the novel are taken from Chatterjee’s non-fiction book, which was very much in the academic mould and sought to draw larger patterns of nationalism and politics in the early 20 th century using some of the facts and records presented in the Bhawal sanyasi case. And Chatterjee himself was rather self-conscious about his role as a ‘neutral’ chronicler who was documenting in the services of future academics. As he writes in the introduction to A Princely Impostor,

“The judges in the Bhawal sannyasi case were faced with the problem, familiar to historians, of deciding which of the conflicting accounts presented before them represented the truth. Can the historian judge the judges? Could I, more than half a century after the law lords delivered their final judgment in London agree to hear the arguments all over again and act, as it were, as another court of appeal? (…) To facilitate such a hearing, and in the spirit of an impartial evaluator of evidence, I have reduced the authorial interventions in my narrative to a minimum. The story here is constructed entirely out of information that can be attributed to definite sources; all gaps in information have been left unfilled and speculative remarks have been appropriately flagged.”

That being said, Chatterjee’s book is quite revelatory and even entertaining, once the court battles begin in real earnest. As we listen to testimony after testimony about the nature of the Bhawal zamindari itself, we learn quite a few things about the past and the present of the place: the geography, the economic realities and so on. Sample this passage, for example, where Bhawal is positioned as a kind of Wild West in the East.

“In the early nineteenth century, Bhawal still had a reputation for being an inhospitable and fearsome place. The Madhupur forest was said to be infested not only by wild animals but also by dangerous humans. There was only one road passing through the area from Dhaka to Mymensingh. There were sparse settlements along the road and the few grocers and shopkeepers who offered food and lodgings to travellers themselves turned into robbers at night. (…) As one revenue official commented, ‘Bhawal, Kasimpur and Talipabad owed their salvation to the dense jungle, which proved a complete deterrent to would-be adventurers.’”

Tollywood’s brush with Bhawal

Although there have been a number of Bangladeshi films and one Uttam Kumar TV movie a long time ago, the best-known cinematic adaptation of the Bhawal case is Srijit Mukherji’s Ek Je Chhilo Raja (2018), which went on to win the National Award. The film is, as one might expect from a deeply commercial, mainstream product, a touch too dramatic at most places. But in one of its sober moments, we see a lawyer played by Aparna Sen ask a question of the powerful men listening to her—what does ‘freedom’, either of the nationalistic kind in the air in those days (at the height of Gandhi’s civil disobedience) or of the kind offered by the royal family, mean to women who are still largely subjugated and expected to fall in line?

In Chakravarti’s novel, too, the court testimonies are used to great effect to gently suggest reasons for the way the peasantry reacted to the mysterious appearance of the sanyasi. Is it possible for at least some of these grateful civilians to be projecting their own need for a benevolent authority? Without spelling it out, the novel seems to suggest so. Look at the specificity of the eyewitness accounts described in this passage.

“The witnesses brought by B.C. Chatterjee surprised the court, not only by their massive numbers and the different sections of society from which they came, but also the quality of their recognition. A gentleman called Kumud Mohan Goswami said that the plaintiff had addressed him at their first meeting as Sadhu Kaka, just as the mejo kumar was wont to do. Ramesh Chandra Sahu, who had worked on the estate for twenty years, said that the plaintiff’s first words to him had been, “Of course I remember you. You are Ramesh babu, nayeb of Kurmitola.” Kailash Chandra Chakraborty testified that he had given the mejo kumar, who was known for his love of birds and animals, a white jackal. The sadhu had remembered the gift and thanked him for it.”

The Bhawal case is a rare confluence of several intersecting themes crucial to understanding colonial India, and it will likely inspire many more writers, artists and filmmakers in the years ahead.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?