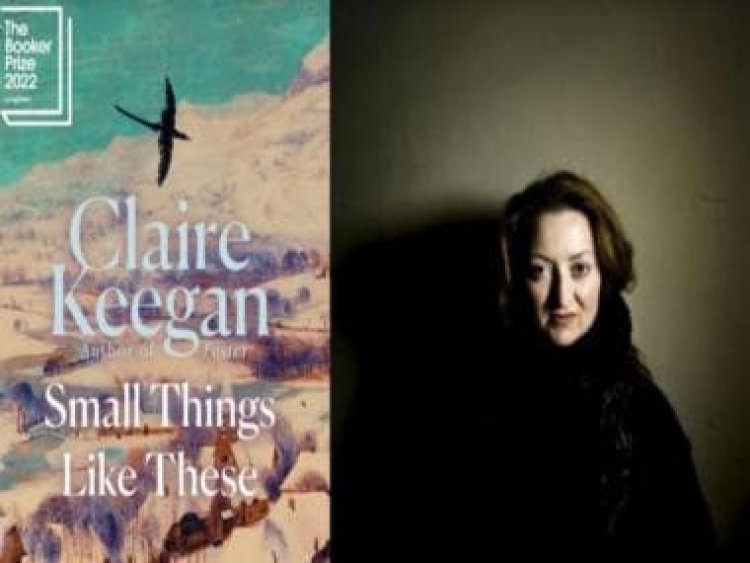

Claire Keegan’s masterpiece ‘Small Things Like These’ is a story of hope in a time of despair

Claire Keegan’s masterpiece ‘Small Things Like These’ is a story of hope in a time of despair

For over two centuries, Magdalene laundries in Ireland housed what people referred to as “fallen women”. Butno one knows how many thousands of “girls and women were concealed, incarcerated, and forced to labour in these institutions,” which were even worse than prisons. “Financed by the Catholic Church in concert with the Irish State,” these institutions remained secretive until 1993 when mass graves of women were uncovered (“one of whom had died as recently as 1987”). The last Magdalene laundry was shut down in 1996; however, a formal apology for the unspeakable crimes that these tens of thousands of women endured and the inhuman conditions they braved came from the then Taoiseach—Prime Minister and head of government of Ireland—Enda Kenny in 2013.

This is the background of the Irish writer of short stories, and arguably the finest among her contemporaries, Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These (Faber & Faber, 2021). Set in 1980s Ireland, this 116-page long work of fictionis the shortest-ever book to be on the Booker Prizeshortlist.

It tells the story ofBill Furlong, who “came from nothing,” as he was raised under the protection of her mother’s employer Mrs Wilson. He was all of 12 when he lost his motherand never knew who his father was. His birth certificate also had unknown written where his father’s name should be printed.But now in his 40s, he’s a coal and timber merchant and lives with his wife Eileen and five daughters. He’s “disinclined to dwell on the past,” as if one’s past was a coal stain one could wipe clean, as if it never was.

It’s Christmas time and the busiest season for Furlong. Even though he’s swamped with work, he’s disturbed by several things. Big or small, depending upon the significance you place in them. It can be a midlife crisis Furlong is going through. Though he owes no one a penny, he isn’t living glamorously either. But deep within, he knows not knowing his father irks him. As he sees his children dwelling on the festivities, he wonders how life would pan out for him if he had a family like as he has now.

Sometimes he wishes to have a mind like his wife’s. Other times he wonders if she’d have fared differently had she not married him. Often the couple indulges in discussing the everyday, the mundane. But there’s something chilling about Keegan’s writing. It’s stone cold. The story is whittled to the minimum possible number of words it can use to tell itself. Its sentences are to die for. They’re adroitly structured, minimalistic, give away their Irishness, and above all render their everydayness magically.

It is not to say that such prose has never been written. Yet there’s something in Keegan’s way of presenting the story that delights you. As twice-winner of the Booker Prize Hilary Mantel notes “a single one of Keegan’s grounded, powerful sentences can contain volumes of social history.” And not only that, but they’re also a commentary on humanness, an utterly disturbing truth facing all of us: What do you do when knowingly don’t make the choice you must make, worrying about disturbing the normalcy?

There are, as Indianism goes, “small-small things” that is striking about this book. Sample this sentence: “Sometimes Furlong, seeing the girls going through the small things which needed to be done – genuflecting in the chapel or thanking a shop-keeper for the change – felt a deep, private joy that these children were his own.” Or this one, “It would be easiest thing in the world to lose everything, Furlong knew.”Each is pregnant with meanings.

This historical fiction, however, reaches its exciting best gradually. Especially when Furlong is out on a delivery to the Good Shepherd nuns-run convent, “a training school,” which “also ran a laundry business.” While “little was known about the training school, the laundry had a good reputation.” The “other talk” in town was that the school didn’t house any students. It had “girls of low character who spent their days being reformed, doing penance by washing stains out of the dirty linen.” Additionally, the illegitimate children born in this asylum of sorts “were adopted out to rich Americans, or sent off to Australia, that the nuns got good money by placing these babies out foreign, that it was an industry they had going.”

Furlong knew all this. Yet, as Keegan writes, “things that [are] closest so often the hardest to see.” It’s one of those days when he gets closest to reality. He finds a young, distraught woman, whose fourteen-weeks-old child has been taken away. But he can’t do anything to help her. On the other hand, at his home, preparation for Christmas is in full swing but Furlong is faced with an uncannily revelation once again, which is really the conflict that propels this fiction.

“It seemed both proper and at the same time deeply unfair that so much of life was left to chance,” Keegan writes. And it’s this chance, this choice one is faced with in life, and if we make the right decision, it makes life worth living. Else one is gnawed with guilt, forever.

Saurabh Sharma (He/They) is a Delhi-based queer writer and freelance journalist.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?