Faraaz movie review: Docudrama-style feature about a terror attack in Bangladesh with a universal message

Faraaz movie review: Docudrama-style feature about a terror attack in Bangladesh with a universal message

Cast: Juhi Babbar Soni, Zahan Kapoor, Aditya Rawal, Sachin Lalwani, Jatin Sarin, Harshal Pawar, Ninaad Sahaunak Bhatt, Reshham Sahaani, Pallak Lalwani, Aamir Ali, Danish Iqbal, Kaushik Raj Chakraborty

Director: Hansal Mehta

Language: Hindi and English

There is something oddly compelling about the words “Gulshan Kumar, T-Series and Benaras Mediaworks Present” laid over one of Faraaz’s imposing opening shots of a giant water body dotted with boats not in India. This is unlikely to be the intention, Benaras just happens to be in the name of one of the production houses backing this new Hindi-English film, but the knowledge that the plot is derived from a real-life terror attack in Bangladesh and not set in the Indian holy city of Benaras standing on the banks of the Ganga, unwittingly underlines the universality of Faraaz’s theme even as it recounts a tragedy that unfolded in another country.

Director Hansal Mehta’s Faraaz is centred around the Holey Artisan Bakery in Dhaka where Islamist terrorists held patrons and staff hostage and murdered 22 of them, 18foreigners and four Bangladeshis, in July 2016. Among the Bangladeshis killed was Faraaz Ayaaz Hossain, According to archival media reports, this 20-year-old scion of a multi-million-dollar Bangladeshi business conglomerate refused to leave the venue when given an opportunity, since it would have meant abandoning his friends, including the sole Indian victim of that Night of Horrors, Tarishi Jain.

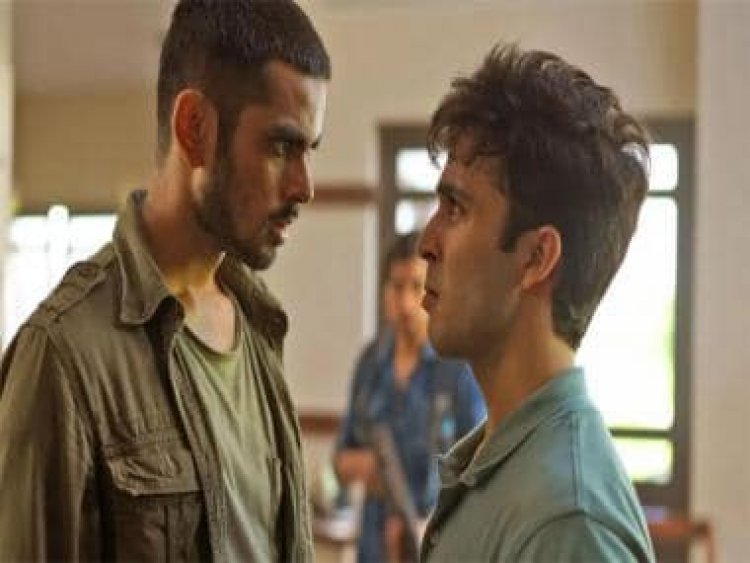

The titular lead (played by Zahan Kapoor), his mother Simeen (Juhi Babbar Soni) and the terrorist Nibras (Aditya Rawal) are largely the focus of the narrative. Faraaz is a docudrama-style fiction feature about the events of that one night that shook Bangladesh.

The goings-on inside Holey Artisan play out in gripping, terrifying sequences without DoP Pratham Mehta’s camera gratuitously shooting the blood or bodies strewn around. It is chilling to note that the terrorists here are not apparently from underprivileged backgrounds but are given the appearance of educated, seemingly well-off youth at least one of whom, Nibras, is personally known to Faraaz. Nibras is contemptuous of Faraaz’s “un-Islamic” ways but does not seem to resent him. His crimes, therefore, cannot be attributed to the brainwashing of a vulnerable individual embittered by the injustices he suffered. The film does not offer him or his associates excuses. In any case we are told nothing about them beyond the information already given in this paragraph that is either articulated or hinted at in Faraaz. These men are hotheads who seem to do what they do because they deem it cool to fight the imagined decline of their religion in Bangladesh. This is the most frightening aspect of Faraaz along with the everydayness in the behaviour of the mastermind of the group who is not at Holey Artisan.

The portrayal of the Dhaka Metropolitan Police and its elite anti-terror unit is less effectively handled. In fact the editing of the shifts from the interiors subtract from the narrative each time. The exterior area also comes across as plastic.

Interestingly enough, despite being based abroad, the conversations in Faraaz echo oft-heard elements in the majoritarian discourse in India. “Islam khatre mein hain,” says Nibras in Muslim-majority Bangladesh, sounding no different from the “Hindu khatre mein hain” refrain among those claiming victimhood within Hindu-majority India.

The commonalities between our two countries as reflected in the Holey Artisan Bakery saga run deeper. Liberals and members of India’s minority and marginalised communities have for long been underlining the complicity of silent liberals in the face of the ongoing minority oppression in this country. It is therefore particularly relevant that Faraaz is about a liberal from Bangladesh’s majority community – a young man of extreme social and financial privilege – who could have escaped but chose instead to stand up for his fellow human beings when they were being targeted for not belonging to his community.

Written by Ritesh Shah, Kashyap Kapoor and Raghav Raj Kakker, Faraaz is “inspired by the book Holey Artisan: A Journalistic Investigation by Nuruzzaman Labu” as per text flashed on screen at the start. The haunting music is bySameer Rahat. As more and more films from India’s other industries give us authenticity in the mix of languages they use, the Mumbai film industry still cannot get itself to make an English and Bangla film set in Dhaka. Still, since the Hindi industry has a long way to go on this front, at least let it be noted that the English dialogues and dialogue delivery sound natural, unlike too many Hindi films of the past.

In 2016 and thereafter, many articles have been written by the world media, including Indian publications, about Faraaz’s heroism. He has also been the posthumous recipient of bravery awards. It is only fair to be concerned that he has not been singled out for plaudits because he was the child of a VIP. The director is well aware of this potential question, and addresses it with text preceding the credits in which he pays tribute to all the martyrs of Holey Artisan. To be just as fair, even though they evoke Faraaz’s actions to convey the larger point of the film, Hansal and the writers do not lionise him, instead injecting believability into his arguments with the terrorists, the conduct of his two companions and the terrorists themselves.

The easily identifiable contentious claim made by the film comes through Faraaz’s fight with his mother Simeen in the beginning because she wanted him to study at Stanford whereas he wanted to remain in Bangladesh. The media has reported that at the time of his death, Faraaz was a student at a US university. This aspect of the fictionalisation was unnecessary, even more so if the intention was to convey his deshbhakti, since there can be no greater bhakti/devotion to your motherland than to speak up, as Faraaz did, for the people who stand upon it.

Faraaz’s considerable lacunae extend to the acting. The film does well not to overly judge Simeen for displaying flashes of class arrogance and throwing “jaante ho main kaun hoon?” (do you know who I am?) at the police team. She is, after all, a distraught mother. Less well done are the writing and acting of the stilted conversation she has with her father on the phone.

In another important scene, Juhi’s decision, presumably on the instructions of her director, to deadpan Simeen’s response to the information that only foreigners were killed inside Holey Artisan and that Muslims were spared seems designed to keep the viewer in suspense about the reasons for her shock – after all, this should have come as a relief to her, since it would have meant her boy got lucky. It doesn’t work although we do get an explanation later on.

This compounds the lack of attention to detail earlier in the narrative. For instance, a hostage receives a phone call from an “unknown number” and when the terrorist asks her to call back, she does. This is too basic a technical miss to be excused. There are also instances when the hostages mutter seemingly crucial lines to each other that are completely indecipherable.

Debutant Zahan Kapoor (Shashi Kapoor’s grandson) and Aditya Rawal (Paresh and Swaroop Rawal’s son whose first film was Bamfaad in 2020), though not stop-in-your-tracks striking here, show flashes of talents worth watching out for.

(Minor spoiler in this paragraph) The pinnacle of cruelty displayed by the terrorists, even more than the physical violence, lies in their decision to force one of the hostages to pose with them for photographs, thus creating the impression to the outside world that he is one of them. This part is well conceptualised and executed, but is marred by a senseless loose end left in the script: everyone inside Holey Artisan witnesses what happens to this man but bizarrely enough, no survivor raises their voice for him when he is later arrested by the police as a terror suspect.

From a filmography spanning over two decades, Hansal Mehta’s works that are perhaps most relevant to a discussion on Faraaz are Shahid (2013), which was based on the true story of an Indian lawyer fighting for Muslims wrongly accused of terror activities, and Omerta (2018), a biopic of Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, the British terrorist of Pakistani descent. While India’s Muslims are being unrelentingly demonised and the community as a whole constantly conflated with Islamist terrorists everywhere, a section of Hindi filmmakers have jumped on to this bandwagon. Hansal, however, has shown how it is possible to portray the average Muslim with empathy and to tell a story of even the worst elements within a community without targeting the community as a whole. Some of the films made by the most bigoted elements in Bollywood have created a ‘good Muslim’ trope to camouflage their stereotyping. This individual is a self-consciously written, all-sacrificing saintly opposite of the evil Muslim who lectures the bad guy/s and whose Muslim identity is underlined in a condescending fashion. Pathaan inverted this ‘good Muslim’ vs ‘bad Muslim’ triteness by placing a non-Muslim at the receiving end of the good guy’s sermon, which might have been commendable if the film had had the courage to write that non-Muslim as a member of India’s religious majority. Instead, Pathaan chose to pick on another vulnerable minority: Indian Christians. Faraaz does neither.

By zeroing in on an actual situation in which an actual Muslim individual, that too a non-Indian from a Muslim majority country, was confronted with an actual Islamist terrorist, that too one shorn of the stereotypical accoutrements assigned to on-screen terrorists, and by writing dialogues that sound like versions of actual conversations that liberals in all communities have with their fundamentalist counterparts, this film steers clear of being patronising.

The question some might ask is whether India needed such a film at all at a time when Muslims are under siege, even if Faraaz’s villains are not Indian Muslims. “Is this the right time for such a film?” The answer is that there is no right or wrong time to make a well-intentioned film about a reality, even if such truth telling could potentially be weaponised against a minority community. The question is, what is the filmmaker’s track record, and what tone do they adopt? I have been thinking about this all week while writing about both Faraaz and a new Malayalam film called Family, an account of the hypocrisy within a rural community of Christians in Kerala. Family is a beautiful film with a message for everyone. Malayalam cinema constantly scrutinises the Malayali Christian community, but these films hold a different meaning in Kerala, a place where Christians, though a minority, exist in larger numbers than their virtually insignificant percentage in the north, and are influential, just like the state’s Muslims. In north India, however, there is a possibility that these same films could be misinterpreted by northerners who have very limited exposure to the Christian community and have been fed a diet of Bollywood’s unrelenting pre-2000s Christian stereotypes. The thing is, any work of art can be misused by twisted minds, so the measure must always be the intentions that come across. Faraaz, like Family, seeks to convey a universal message, and that is the barometer by which it must be judged.

I can’t help but wonder what Faraaz might have been if it was confined entirely to the developments in Holey Artisan. That said, though this film is wanting in many departments, what it gets right makes it worth watching.

Rating: 2.5 (out of 5 stars)

Faraaz is in theatres

Anna M.M. Vetticad is an award-winning journalist and author of The Adventures of an Intrepid Film Critic. She specialises in the intersection of cinema with feminist and other socio-political concerns. Twitter: @annavetticad, Instagram: @annammvetticad, Facebook: AnnaMMVetticadOfficial

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

What's Your Reaction?