Food Friday | Durga Pooja: Remembering grandma’s pooja delights

Food Friday | Durga Pooja: Remembering grandma’s pooja delights

It is small wonder that Durga Puja received the UNESCO tag of Intangible Cultural Heritage, as it has been such an integral part of a Bengali’s life for eons. It was a catharsis long pending. The Goddess Durga’s famed visit to her maternal home after slaying the demon Mahishasur is the ritualistic reason for the week long festivities, but for someone like me who belongs to the first generation of India’s nuclear families; it was more of a homecoming. The phenomenon holds true even today for millions of Bengalis spread across the world looking forward to coming home during this auspicious time of the year, and I suppose it will always be so. An eternal tradition in the truest sense of the word.

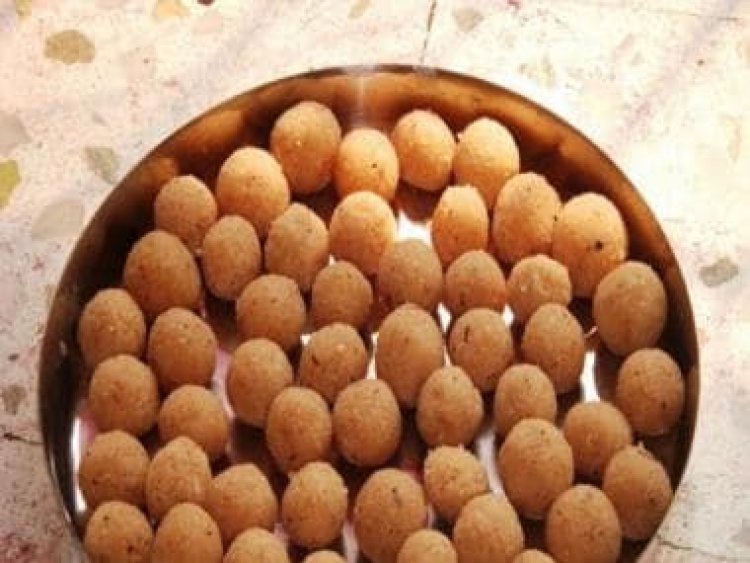

A warm feeling of being with the loving grandparents once a year drove our (my sister and I) excitement levels to a wondrous high. As October approached, we would imagine the various goodies we were going to devour in our maternal home and the things we would bring back and share with friends in school after the holidays. You see, much of the goodies we will talk about today could be naturally preserved for weeks, and had a decent shelf life to last at least till Diwali that comes 20 days after Vijaya Dashami. I am referring to the quintessential Naaru (coconut laddoos with jaggery and elaichi), the Nimki (deep fried savoury wheat fritters), Goja (caramel coated wheat fritters with a soft inside) and such homemade delicacies.

No, of course these items are not restricted to a Bengali household but you have to believe when I say that Bengalis have the skill to instill nostalgic value into a recipe like no one else. I lost both my grandparents in the recent years, and it broke my heart when my loving Grandmother sought heaven just before Durga Puja in 2021. She left a hollow that could never be refilled. A grandparent’s love is unconditional, so profound that it leaves a significant mark on an impressionable kid’s persona forever. I feel most fortunate to have a set of such deep source of love from my Mother’s side, who not just nurtured us with the many fruits and foods of their garden, but also helped me become what I am today. It was my Dadu who was the real writer. In his pearly handwriting, he used to teach me literature and help me with writing long form essays and taught me the constellations in the night sky. My grandmother on the other hand was what anyone calls an epitome of selfless love. This time of the year brings a sense of profound loss to me now, when the glitz and glamour of the festivities seem to fade away emboldened by my loss of the one true guardian angel in my life.

I remember her soft bangle clad hands going “trrr trrr trrr” in a rhythmic motion as she rolled the naarus. I’ll be honest, I did try to learn from her but never could get the viscosity and balance of the jaggery-coconut quite right. My mother came close, but even she couldn’t master the trick. I am afraid we will never know now. Naarus can be made with different objectives, soft ones for offering to the God’s, harder ones to fill tins travelling far across the world in the suitcase, white ones for those who either don’t like jaggery or love the coconutty-ness as is, with elaichi or without, with dry fruits and so on. Even the kind of jaggery used makes a lot of difference my Grandma used to say.

She maintained a dictator like attitude when it came to sourcing the ingredients for the annual stash of ‘naaru’ with a Chef’s precision. Fresh palm jaggery only would be accepted, the one we call ‘Jhola Gur’ as it could be kept in earthen pots hung anywhere on a hook. The dark brown semi-viscous liquid is a prized collection as winter approaches in rural Bengal. Dida(Grandma) used to say, “You get the right Gur and half the job is done, and if you put it on low heat and continuously keep mixing the grated coconut, you will get a tight mixture that makes the shape hold.”

A few days ahead of the elaborate making process, the coconut was brought down from the trees in the garden. My grandfather supervised as a nimble fellow tied a rope on his waist and climbed up the branchless tree in a swift gravity defying dalliance. A pile was built and then the ripe ones were sorted out from the unripe ones (Daab). They would either be drank raw or used in making ‘Daab Chingri’, a coastal Bengal delicacy famous globally.

I remember Dadu and I would sit together and tear away the husk from the ripe ones using whatever blunt tools we could find – a gardening hedge shears or a digging fork. It took hours but at the end of it, we would have neatly stacked coconuts. My mother and sister would take over from here, break them in halves and painstakingly grate them using a traditional grater that you put your feet on to keep steady.

The nimki arrived on the evening of Vijaya Dashami as neighbours started pouring in to offer greetings and touch the feet of elders, in this case, my grandparents. Making Nimkis took only a couple of hours with Dida making the dough, signified with the fresh Kallonji seeds poking from it. She would lay it out on a steel plate with high edges and flatten it out in the shape of the vessel. I was given the honorary task of cutting it into diamond shaped ‘nimki’, which was then deep fried in very hot oil in a deep iron kadhai. Sprinkled with a little rock salt, the nimkis would be served with a few naarus and a plate of other store bought sweets like Rosogolla, Pantua and Chhanar Jilipi to the visitors.

They would indulge and engage in talks with Dadu. In minutes, the plates would be empty, but no one would dare ask a second helping because they had more houses to visit, and the plate more or less remains same with a few alterations. It was like being on a ‘naaru-nimki’ competition as a Judge, going to each house and considering the goodness of it all. Although fascinating, I was content with my share of it firstly because it was unlimited in supply and also because I will never believe anyone could make it better than my Gran.

The Goja was not my favourite, but sometimes she would give it a twist and make ‘Balushayi’ instead. A puff with sweet coconut filling shaped beautifully like a shapta (a North Eastern pie).

The coconut laddoo is common across India’s coastal areas but the mixture and process differ slightly. Like the filling for a Modak and a Balushayi is quite different. Or take the Goan Patoleo, a steamed dumpling like modak but different yet.

Go anywhere coastal in Asia and you’ll find a local rendition of coconut balls, that is an undeniable truth of the simplicity of the item. For me, it will always bring me happy memories of the two best people in my life, who I spent the best Durgapujas. Shubho Sharodiya!

(Chandreyi Bandyopadhyay is a travel and food writer and blogs at themoonchasers.com)

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?