France to ban abayas in school: The country’s long history of veil bans

France to ban abayas in school: The country’s long history of veil bans

Students in France’s public schools will no longer be allowed to wear the abaya, a loose-fitting, full length dress some Muslim women adorn.

Ahead of the new term beginning on 4 September, Education Minister Gabriel Attal announced on Sunday, “I have decided that the abaya could no longer be worn in schools.

“When you walk into a classroom, you shouldn’t be able to identify the pupils’ religion just by looking at them,” he said to TV channel TF1.

The move is a long line of steps that France has been taking against what they term as an ‘affront to secularism’. However, there are many others who call it a sign of rising Islamophobia in the European nation.

Also read: Hijab must in Iran, burqa banned in France: Countries that dictate what women should wear

The ban on abayas

Before we delve into the matter of the ban, here’s a simple explainer to what an abaya is. It is typically a black garment constructed like a loose robe or kaftan and covers everything but the face, hands and feet. It’s important not to confuse the abaya with a burqa or hijab – other Islamic forms of dress for women. The burqa is a garment that covers the entire face, with a crocheted mesh grill over the eyes. The hijab, on the other hand, is a head scarf. Styles vary not only by geography, but also fashion trends.

Declaring a ban on abayas in state-schools, Education Minister Attal described the Islamic garment as “a religious gesture, aimed at testing the resistance of the republic toward the secular sanctuary that school must constitute”.

In France, there’s a strict ban on religious signs at schools since the 19th Century, including Christian symbols such as large crosses. The ban also includes Muslim headscarf and Jewish kippa.

Attal’s decision to ban abayas from the coming term in French state schools has been welcomed by the right and far right who are seeking to curb the growing role of Islam in French society. Head teachers’ union leader Bruno Bobkiewicz welcomed the announcement.

Eric Ciotto, head of the opposition right-wing Republicans party, also welcomed the news. “We called for the ban on abayas in our schools several times,” he said.

But Clementine Autain of the left-wing opposition France Unbowed party denounced what she described as the “policing of clothing”. Attal’s announcement was “unconstitutional” and against the founding principles of France’s secular values, she argued – and symptomatic of the government’s “obsessive rejection of Muslims”.

The French Council of Muslim Faith (CFCM), a national body encompassing many Muslim associations, has said items of clothing alone are not “a religious sign”.

France’s many bans

The ban on abaya is a continuation of France’s war against Islamic garments. In 2010, the European giant banned the wearing of full face veils in public which led to anger among the country’s five million-strong Muslim community.

The only exception to the rule was when worshipping in a religious place or travelling as a passenger in a car.

The reasoning behind the law was to prohibit the concealment of the face in public spaces. Lawmakers who supported this legislation also said that headscarves and face coverings was a sign of oppression faced by women, which in turn is believed to be an embodiment against secularism – an ideal highly regarded in France.

A year later in 2011 the Nikolas Sarkozy government banned the wearing of the hijab and even turbans in school classrooms.

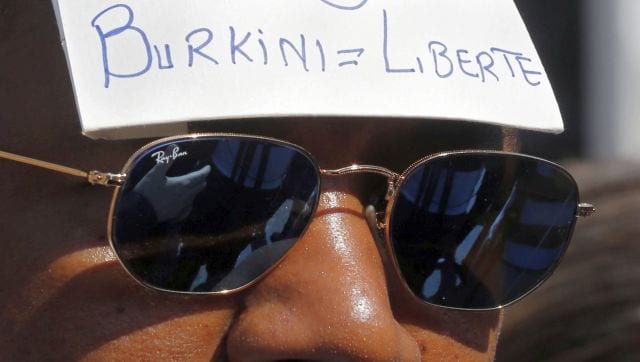

The summer of 2016 saw the anti-burkini decrees announced across the country. Muslim women were barred from wearing swimsuits that covered their body completely. It began with the cancellation of a “burkini” event at a water theme park in Marseilles. Then the Riviera town of Cannes banned the full-body swimsuit on its public beaches.

Then Prime Minister Manuel Valls had expressed his support for the bans, saying the swimsuit represents what he calls a “provocation” and “an archaic vision”. In June last year, the nation’s highest administrative court upheld the ban on the wearing of burkinis in public pools after the authorities in Grenoble had challenged it.

And despite footballing body FIFA has lifted its ban on female athletes wear the headscarf during international matches in 2014, France’s footballing institution – the French Football Federation (FFF) – maintains a ban on the wearing of “conspicuous religious symbols”, which includes the headscarf.

Taking this forward, the French Senate in January last year voted 160 to 143 to ban the wearing of the hijab and other “ostensible religious symbols” in all sports competitions. While proponents maintain the move is to uphold neutrality in sports, critics call it “gendered Islamophobia.”

Shireen Ahmed, senior contributor with CBC Sports, had told CNN then, “Excuses of ‘we want laïcité and we want secularism’ – they’re really a shield, because they don’t apply fairly to the men performing crosses before they step onto the pitch.

“Where’s the consistency here?” she said. “It’s a deliberate exclusion.”

Fatima Bent, head of French feminist and anti-racist organisation Lallab, also told the American news outlet that “this argument of banning the hijab has nothing to do with liberation, helping Muslim women, and nothing to do with sports conditions.

“This discourse stems from this colonial European approach where Muslim women are always depicted as women to save: from their families, their origin, who have to deny their identities to assimilate.

“It is a continuation of a story of a European colonial power that asserts dominance, asserts that Muslim women submit, and considers them as inferior,” she added.

In June this year, however, the country’s top court once again said that the country’s soccer federation can ban hijab even though the measure limits freedom of expression

France’s growing hate of Islam

Earlier in June, the killing of 17-year-old Nahel M in a Paris suburb, spawned mass protests and anger across the country, with many calling it the face of France’s Islamophobia.

Salman Sayyid, professor of social theory and decolonial thought at the University of Leeds, told Anadolu News later that the French state and sections of its society have been “pursuing an Islamophobic orientation for a number of years.” “I think it (Nahel’s killing) is a sign of institutional Islamophobia and institutional racism in the French law enforcement system, in the French criminal justice system, and in the French state itself,” he told Anadolu.

He said the French police’s attitude toward people “especially those that are considered to be ethnically marked or marked by Muslimness is institutionally racist and institutionally Islamophobic.”

A previous study has also revealed that a growing number of Muslims were leaving the country, seeking employment in areas that were more tolerant of their religious beliefs. Professor Olivier Esteves of the University of Lille said that he had interviewed 1,074 Muslims who left the country of which more than two-thirds reported that they moved to practice their religion more freely, while 70 per cent said they left to avoid racism and discrimination.

It’s also important to note here that France recently also voted against the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in the wake of a Quran-burning stunt in Sweden. France’s ambassador Jerome Bonnafont had then noted that human rights “protect people – not religions, doctrines, beliefs or their symbols … It is neither for the United Nations nor for states to define what is sacred”.

With inputs from agencies

What's Your Reaction?