How Demon Copperhead revitalizes Dickens for a new era

How Demon Copperhead revitalizes Dickens for a new era

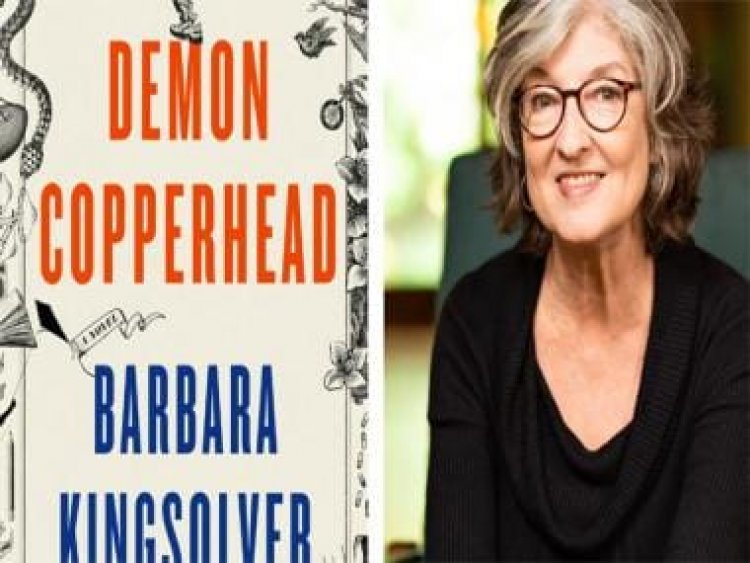

Earlier this week, Barbara Kingsolver’s novel Demon Copperhead was announced the joint winner of the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, alongside Hernan Diaz’s novel Trust. The 68-year-old Kingsolver’s works (including and especially her bestselling novel The Poisonwood Bible, about a family of missionaries in Congo) have been praised by critics around the world for their emphasis on social justice, inequality and ecological issues. Kingsolver lives with her family on a farm in Southwestern Virginia, which is part of America’s Appalachia region (Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, North and South Carolina and so on).

Demon Copperhead is set in the Appalachia region, and is a reworking of perhaps the most nakedly sentimental (and personal favourite of the author) of all Charles Dickens novels; David Copperfield. Kingsolver’s protagonist Damon Field is born, in the 1980s, to a trailer-dwelling, substance-abusing mother who’s high on gin, amphetamines and painkilling pills at the time of his birth. Damon (who soon acquires the moniker ‘Demon’ and has an absentee father with the last name ‘Copperhead’) is pretty much brought up by his abusive stepfather Murrell Stone (known as ‘Stoner’, a stand-in for the Dickensian Mr. Murdstone) and the Peggot family next door, led by the redoubtable Mrs. Peggot, who had delivered Damon all those years ago.

Demon Copperhead has some of the same preoccupations as Dickens’ original—what widespread, institutional poverty does to children, how the system fails these kids, the effect that lingering trauma can have upon the juvenile consciousness. Kingsolver’s genius is to tie these threads together with one overarching Big Bad—America’s opioid crisis, especially the role played by OxyContin and its makers, Purdue Pharma (owned by the Sackler family, who admitted to their company’s role in the crisis and yet, went largely scot-free).

By the time he’s five years old, Demon finds himself working at a local meth lab (he doesn’t know what exactly he’s doing, but that doesn’t reduce the risk, of course). A brief oasis of peace and stability follows with high school football. But this is a Dickensian plot, after all, and the tragedies never stop coming. After a freakish injury on the field, Demon finds himself trapped in the vagaries of America’s medical system (which is perhaps the institution that cops the most blows across the novel). Demon is worn down by the endless waiting periods, the creative accounting of the insurance companies, the all-round apathy showed by underpaid and overworked hospital staff. And after all the rigmarole, Demon realizes that in the interim period, he has gotten hooked onto painkillers. According to the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) figures, over 100,000 people died in America due to prescription drug overdoses and/or illicit drugs in 2021 alone.

American mythology, American delusions

Kingsolver’s descriptions of the ‘white trash’ dwellings in Lee County, Virginia, betray the extent of poverty and despair in these settings. Often, Kingsolver ends the passages in this vein with a typically American wise-crack, riffing off popular sayings, comicbook quotes or superhero movies. Take this passage, for example, where Demon describes the squalor and the hopelessness projected by the Peggots next door.

“The Peggots next door in their yard had a birdhouse on a pole that was a big mess of dangling gourds, with holes drilled for the bird doors. It was the bird version of these trailer pileups you’ll see, where some couple got a family going and nobody, not kids nor grandkids, ever moved out. They’re just going to keep shacking up and hauling in another mobile home to set on blocks, keeping it one big family with their junkass porches and raggedy flag over the original unit. One Nation Under Employed.”

That last bit—One Nation Under Employed—is a play on the dictum ‘One Nation Under God’, taken from the ‘Pledge of Allegiance’. Quoting from the Pledge of Allegiance is an ever-popular gambit among American politicians keen to underline their Christian credentials. Kingsolver seethes with rage at the cynical way in which these politicians exploit people’s religious feelings and dupe them into signing off on anti-poor, anti-working-class policies. Some of this rage is felt in the midst of passages where Demon sorts out his complicated feelings about the Bible.

“But some of the Bible stories I minded, definitely. The Lazarus deal got me mentally disturbed, thinking my dad could come back, and I needed to go find him. Mrs. Peggot told Mom I ought to go see Dad’s grave in Tennessee, and they had a pretty huge fight. Maggot calmed me down by explaining Bible stories were a category of superhero comic. Not to be confused with real life.”

In this passage, there’s mental illness, there’s a Biblical allegory, there’s an ill-fated attempt at keeping the nuclear family unit together… and it’s all rounded off by a reference to superhero comics. In short, a quick rosters of both American mythology and American delusions.

Dickens in Appalachia: How we let at-risk children down

Charles Dickens published David Copperfield as a standalone book in 1850, after the novel had been published in serialized instalments over the preceding couple of years. The novel was a bildungsroman, in that it showed how an orphan overcame one barrier after another to become a respected, well-known writer. But Dickens’ politics could not have been clearer. David Copperfield was an indictment of society’s treatment of vulnerable, at-risk kids. Children growing up in abject poverty, children growing up without responsible, full-time guardians, children out on the street scrounging for food when they should have been receiving an education instead.

By moving the action from the 1850s to contemporary Appalachia, Kingsolver is telling us that the more things change, the more they remain the same, at least for at-risk children. Early on in the novel, we see Demon’s mother marrying her abusive, authoritarian boyfriend Stoner. Not because he has other fine qualities (he has none) but because his crappy job as a truck driver comes with a silver bullet: health insurance. For the first time, Demon and his mother can think about visiting a doctor or even (gasp) a dentist.

“‘Medical and dental’ was the part that got Mom excited. I would have coverage now in case I needed my tonsils out or got hit by a car. Or the ADHD drugs that some teachers had been wanting Mom to put me on from day one. Stoner said oh, yes, the riddling or whatever would take me down a notch. Mom was on the fence. But she said definitely I was going to the dentist now, whether needed or not. Which I wasn’t thrilled about.”

When you read passages like these, you understand why the American public has showed consistent, bipartisan support for issues like Medicare For All (championed by prominent progressive Senators like Bernie Sanders), a socialised healthcare system that would not discriminate based on income levels (and would not leave the average American bankrupt on account of a one-day visit to the hospital).

Among the more impressive creations of Dickens in David Copperfield was the character of Mister Micawber, the impossibly stoic, simple-minded man who’s misled by the scheming Uriah Heep. As a result, he hurts David inadvertently. In Demon Copperhead, however, the Micawber prototypes are downright evil, however. “Mr and Mrs. Cobb” run the foster home that takes Demon in after his mum overdoses and he becomes the “inventory” of an apathetic social services system. Mr and Mrs Cobb are only interested in keeping Demon under their roof because of the welfare cheques. As long as the cheques keep pouring in, they couldn’t be less concerned about what Demon did with his time.

In general, both Dickens and Kingsolver take a dim view of state-mandated welfare services. For Demon Copperhead, this means the DSS (Department of Social Services), where underpaid and ennui-laden workers were the embodiment of inefficiency and callousness.

“If you are the kid sitting across from her in your caseworker meeting, wearing your two black eyes and the hoodie reeking of cat piss, sorry dude but she’s thinking about what TV show she’ll watch that night. Any human person with gumption would have moved on to something else by now, the military or selling insurance or being a cop or even a teacher. Because DSS pay is basically the fuck-you peanut butter sandwich type of paycheck. That’s what the big world thinks it’s worth, to save the white-trash orphans.”

That last bit about what ‘white-trash orphans’ are worth to the world—that’s the aspect which Kingsolver wants to amplify above all with her masterpiece. After her Pulitzer win was confirmed, Kingsolver told Associated Press, “I wrote this book for my people because we are so invisible to the rest of the world and so persistently misrepresented.” Well, Demon Copperhead has made sure that the inequality and systemic deprivation of Appalachians are a little more visible today than they were the day before. And as the epigram to Demon Copperhead (borrowed from David Copperfield, of course) says, “It’s in vain to recall the past, unless it works some influence upon the present.”

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?