In a class of her own

In a class of her own

One of my favourite biopics of all time isn’t really a biopic at all: Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There, a series of impressionistic sketches inspired by “the music and many lives of Bob Dylan”. Six different actors, including Cate Blanchett, Heath Ledger and Christian Bale, play different ‘aspects’ of Dylan, characters inspired by various phases in Dylan’s life. I’m Not There works, despite breaking every widely-circulated storytelling dictum there is, because it revels in its own uniqueness instead of hedging its bets.

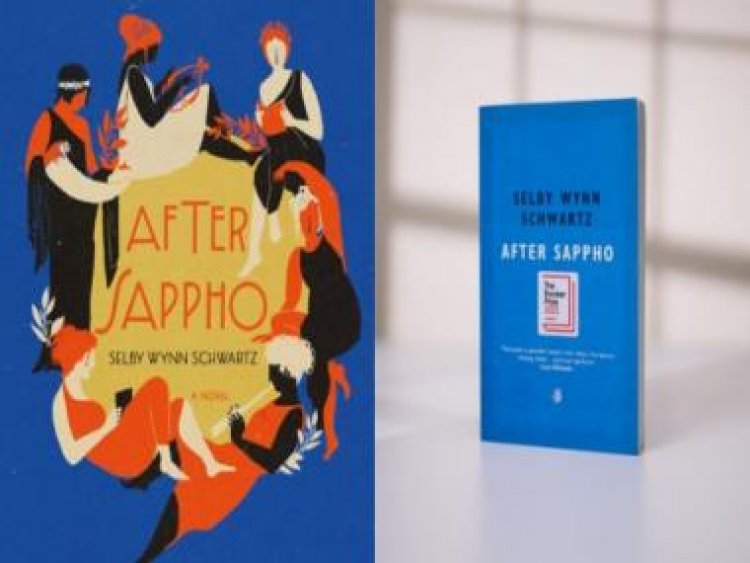

Selby Wynn Schwartz’s novel After Sappho (longlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize) belongs to a similar category in contemporary literature. I can think of very few recent books that are as unique, structurally speaking. In this Greek chorus of a novel, we move from 1880s Italy, where the poet Lina Poletti refuse to be swaddled, to London and Paris in the interwar period. And throughout this literary Doctor Who adventures in space and time, we meet women who abandon their given identities to craft new ones, embracing queerness in both their personal and professional lives: Virginia Woolf and Rita Sackville-West, Isadora Duncan, Sarah Bernhardt and many, many others. Throughout the book, Sappho’s poetry (Schwartz has used the Anne Carson translation, which is reliably brilliant) is used to bring these women’s choices and idiosyncrasies into sharper light, and the results are awe-inspiring.

In this novel, the same passage can be read as historiography, satire and un-ironic biography; that’s how cleverly certain especially brilliant passages are written here. Sample this, for example, from quite early in the book, when the reader is introduced to Anna Kuliscioff, the Russian-Italian revolutionary who was one of the first women in Italy to have a graduate degree in medicine.

“Anna Kuliscioff was so often the object of outcry and imprecation that by 1884 she scarcely registered an insult. She enrolled in the University of Napoli to study medicine, despite the fact that no woman had ever done so before. She was interested in epidemiology and why on earth so many Italian women were permitted to die from puerperal fevers. At her graduation in 1886, when she was decried as a pathological perversion of femininity, Anna Kuliscioff paused briefly to recite the correct medical definition of ‘pathogenesis’. Then she took her degree.”

The bit about puerperal fever in Italy is important because it’s a reminder of the way lesbian relationships would be written about in pathological terms, often in medical textbooks or ‘advisory’ booklets. In fact, Schwartz lampoons one such medical practitioner from the 1840s, writing about “Dr T. Laycock’s A Treatise on the Nervous Disorders of Women (1840)”.

“The eminent Doctor Laycock of York, writing on the nervous disorders of women, could not help but notice that the more young women consorted with each other, the more excitable and indolent they became. This condition might strike seamstresses, factory girls, or any woman who associated with any number of other women. In particular, he cautioned, young females cannot associate together in public schools without serious risk exciting the passions, and being led to indulge in practices injurious to both body and mind.”

The “practices injurious to body and mind” euphemism may be hilarious to modern-day readers, but almost 200 years ago there was the very real fear that if you were confirmed as a homosexual, you’d be bundled off to an asylum and administered all kinds of pseudo-scientific ‘cures’. As Schwartz writes:

“Novels, whispers, unsigned poems, general education, shared sleeping compartments: no sooner were girls reading in bed than they were reading in bed together. What might look like sisterly affection or a schoolgirl’s fancy ought to be diagnosed as the pernicious antecedent of hysteric paroxysms. In the throes of it they were highly contagious and might throw whole households into disorder.”

For me, personally, the most enchanting bits of the novel were the ones featuring Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), one of the most influential writers in the English language. Schwartz captures the relationship between Woolf and Rita Sackville-West and also gives us some beautiful scenes set during the writing of Orlando, Woolf’s most personal and expansive novel, about an ageless, immortal poet who lives for hundreds of years, changes from man to woman and ends up meeting nearly every key figure from English literary history. For obvious reasons, this novel has become a staple on syllabi pertaining to queer and transgender studies.

Woolf in contemporary literature: Michael Cunningham, Priya Parmar et al

“She herself has failed. She is not a writer at all, really; she is merely a gifted eccentric. Patches of sky shine in puddles left over from last night’s rain. Her shoes sink slightly into the soft earth. She has failed, and now the voices are back, muttering indistinctly just beyond the range of her vision, behind her, here, no, turn and they’ve gone somewhere else. The voices are back and the headache is approaching as surely as rain, the headache that will crush whatever is she and replace her with itself. The headache is approaching and it seems (is she or is she not conjuring them herself?) that the bombers have appeared again in the sky.”

This heart-breaking, impossibly beautiful passage (about the moments leading up to Virginia Woolf’s suicide) is from Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours, which won a Pulitzer in 1998 and was later adapted into an Oscar-winning film. The narrative follows three women connected to Mrs Dalloway, perhaps Woolf’s most widely-read novel. There’s Clarissa Vaughan, a 52-year-old publisher in 1999, a kind of 90s Mrs Dalloway who’s preparing for a dinner party just like her fictional counterpart. Clarissa and Sally are partners and are throwing a party in the honour of ailing poet Richard Brown, whose mother Laura Brown is the novel’s second protagonist. Circa 1949, Laura is reading Mrs Dalloway for fun while being trapped in a loveless marriage. The third woman, of course, is Woolf herself circa 1923, when she is about to start writing the novel.

Cunningham’s novel was also adapted into an Oscar-winning novel by the British director Stephen Frears, and Nicole Kidman won an Oscar for her portrayal of Woolf. Since then, there have been so many other writers who have been inspired by the life and works of this magnificent writer: Hermione Lee, Susan Sellers, William Boyd and so on.

One of the most enjoyable works for me in this regard was Priya Parmar’s novel Vanessa and her Sister, which explored the relationship between Woolf and her sister, the artist Vanessa Bell. This epistolary novel—for it proceeds almost entirely in the form of letters written between sisters—is a lot of fun, not least because of the ‘comedy of manners’ it both channels and subverts, at various points in the story. In the following passage, for example, we see Woolf correcting an arrogant man at a party about the facts of Sappho’s suicide.

““Sappho? I am sure Sappho drowned,” Desmond called out from the green chintz sofa.

“Sappho leapt to her death,” Virginia said, her voice cracked and low like a distant thunderclap. “Euripides was killed by dogs.”

Everyone leaned in to hear her.

“And Aeschylus?” Thoby asked, proud of her for knowing the answer.

“As prophesied, Aeschylus was killed by a tortoise that fell from an eagle’s claws,” Virginia said without hesitation.

Later in the evening, Virginia found her pitch. Morgan asked her about her writing, and Virginia was brief, clear, and disarming. She spoke of rightness and beauty in the unfettered, clean phrasing she prefers. Her voice broke free of its rusted shell and slid like a deep river over rocks.”

After Sappho joins the ranks of these delectable, Woolf-inspired works, then. Towards the end of the book, Schwartz gives us the final passage involving Woolf and Sackville-West, where the former is explaining her vision of what Orlando is supposed to be. It’s remarkably written but also…she could have been talking about her own novel.

“This was a biography, the title announced. But it was also a novel, a whole fantasy, a view of two women at the top of a house, a talk on fiction and the future, a new biography, fragments of a sapphic poem, a composition as explanation, a heroically private joke, a series of portraits, a manifesto, an alcove in the history of literature, an alchemical experiment, an autobiography, and a long piece from life now. In fact, no one could tell what was its genre, it was as mercurial in mood and ample in form as Orlando themselves. Every time Orlando awoke, there were many more lives.”

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?