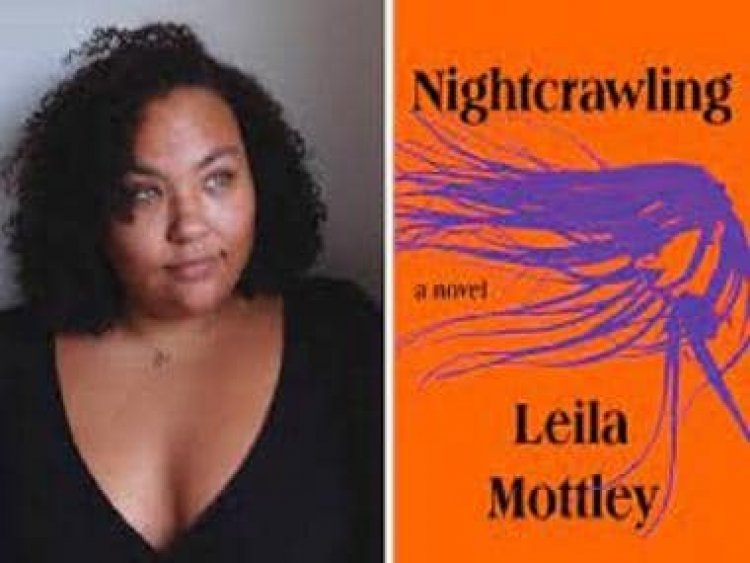

Leila Mottley's Nightcrawling: A brilliant, technically accomplished debut novel

Leila Mottley's Nightcrawling: A brilliant, technically accomplished debut novel

There’s a scene early on in Leila Mottley’s debut novel Nightcrawling (which is on the longlist for the Booker longlist, making the 20-year-old Mottley the youngest-ever author in contention) which makes the socio-economic underpinnings of her story painfully clear, without ever trying too hard. The 20-year-old writer had based the bare bones of her story on a real-life police investigation in Oakland, California that happened when she went to high school there—a prostitution ring involving multiple police departments and the sexual exploitation of a young woman. Out of this outline emerged Mottley’s irrepressible 17-year-old protagonist Kiara Johnson, a poor Black woman from a deeply dysfunctional family who turns to sex work to avoid being evicted.

In this scene, Kiara and her friend Alé are at the nearby Joy Funeral Home — a frequent venue for them because they’re perennially short on food and clothes. The friends realize at first that they aren’t dressed in black, and then decide that it doesn’t matter, because in a “hood funeral” nobody cared. In a neighbourhood like theirs it did not matter because people had become benumbed to the constant loss and resultant depression.

“And suddenly we’re both giggling because she’s right and we must have known this, since we’ve never shown up to a funeral in anything but jeans and stained T-shirts, except for when Alé’s abuelo died two years ago and we wore his shirts, ones that had yellowed from age and smelled only of cigarettes and clay from the deepest, most fertile part of the ground. No mortician ever interrogated the mourner’s apparel just like they don’t stop and ask about no stab wounds. I showed up to my own daddy’s funeral in a neon-pink tank top and nobody said a word.”

As is apparent in this passage, Mottley’s is a unique voice, strong and flexible in its approach to everyday tragedies. There’s just the right amount of bleak poetry here to soften the (potentially) unpalatable bits of the story she is telling: Kiara’s, that of a young girl who becomes victimized in all sorts of horrible ways because deep down, she has convinced herself she’s always going to be on her own, that every single societal structure built to support those in her position will invariably let her down (and looking at the novel’s indictment of American political and economic policies, it’s tough to argue otherwise). As Kiara is exploited in increasingly horrible ways in the first half of the novel, not once do we feel that the authorial gaze is less-than-honest or facile. This is a testament to the strength of Mottley’s craft and what she has achieved here, blending pathos with a brand of gallows humour all her own.

The dialogue of a poet

Not that she cannot be funny in other, more straightforward ways. One of the many darkly funny strands in the book has to do with Keira’s brother Marcus, a traumatized young man (he discovered his mother lying half-dead in a bathtub after a suicide attempt) who is hellbent on making it as a rapper despite having no discernible talent, charm or business sense. A brutally funny passage not long after we first meet Marcus takes apart his pretensions as well as gently hints towards the trauma and the isolation that has led to his current state. It's a remarkably tough balance to strike, that too in one’s debut novel.

“Tupac might just be shivering in his grave because my brother don’t know how to spit, and the only words I can hear in the mess of his tongue are bitch and ho and this nigga got chains and I wanna tell him this room knows how he hurled into our toilet for two weeks after Daddy died because his body cannot bear grief. This room knows how the only chains he got are from those machines that spit out plastic containers for fifty cents at the arcade. This room knows the only bitch he got is me and I’m shrinking back, trying to disappear myself into the doorway the way Marcus disappears us in his lyrics.”

Note the effortless rhythmic feel of this passage, the music of it, capped by the hat-trick of lines that begin with ‘this room knows’. This is a passage critiquing somebody else’s poetic pretensions, and it reads like poetry written by a seasoned, middle-aged writer, not a teen prodigy. And this is true for most of the ‘family portraits’ Mottley draws up for Kiara across Nightcrawling. When we meet her Dad at first he is introduced as a proud ex-Panther (we are shown how other members of the Black Panther party supported him in public), a man who was once formidable, both physically and in terms of his cheerful disposition. Years of hard knock in prison has dimmed the glow since, but every now and then we get a glimpse of what the character was like in his youth. It’s extremely subtle writing and displays a fine understanding of both plot progression and character development. See how her Dad’s happiness at a drum circle is connected to both the pleasures and the dangers of his own life, as well as his relationships with those around him. It’s like a poetic, oblique biography in miniature.

“Daddy always knew how to enter the music, his hands slapping, chin tilting in every direction. This newly free man bobbing like he hadn’t seen the things he’d seen. Mama stood straight and still, faintly swaying, and I could tell she was waiting for something to happen. Waiting for Daddy to collapse. But he didn’t. He just kept on slapping that drum, grinning at us. Eventually, he gave the man his drum back and Daddy went over to Mama and whispered in her ear until, finally, Mama’s mouth opened wide and the melody came out like it had just been uncaged. Daddy separated from her and started clapping, looking at everyone around him like Damn, that’s my woman, look at her sing.”

By the time the police corruption and extortion segment of the novel begins I was in awe of Mottley’s sheer control of narrative voice. Kiara is easily the most memorable protagonist I have come across this year in fiction, an unforgettable mixture of tenacity and vulnerability. She refers to the police officers by their badge names, reflecting the lengths to which American society goes to protect cops, even when they know all about their misdeeds.

“190 pays me and then leads me through the door, holding my hand, and everyone within sight explodes into applause and beer-fueled roars that remind me of Marcus and Cole when they think they got a platinum song on their hands. 190’s hand is colder than mine, but they’re the same color and it almost looks like our skin has been knitted together. From what I remember from the last time I saw 190 at the Whore Hotel, he likes to talk. Takes me to the parking lot and gets me in the backseat of his car, fondles a little, but mostly he just divulges everything he’s been sealing into the lining of his throat. Told me about how his daddy’s not happy he joined the force, said he done raised his daddy like he was the parent and not the child, let the crevices of his body flood. Men don’t mind crying as much if they pay for it, knowing they won’t have to see me again if they don’t want to.”

That devastating last lines shatters the edifice of the cold, unfeeling villainy built by the previous ones. It’s a supremely clever one-two and allows us to see 190 as an object of pity, and not just as a regular old monster. Nightcrawling is full of bravura sequences like that one, including a home birth passage involving a circle of women and a pipe filled with crack cocaine that I am not forgetting in a hurry.

“Dee wailed and squeezed and trembled until my mama’s hums drowned it all out and then the tribe of us saw the hair, saw the tiny round that crawled from her body, turning her inside out. The squeals began and the humming turned to chants and we all watched that child swim out his mama, head poking out more blood than hair, and my mama took him into her arms and laid him on Dee’s breast and this was the sweetest, most whole thing to ever take place in our building, and the rain poured and poured and poured until Dee began to beg again and her birthmarked baby squirmed and Ronda gave up, passed Dee the pipe, and she faded into sky like she didn’t hear her own baby crying.”

Leila Mottley’s Nightcrawling is one of the books of the year and regardless of whether it wins the Booker eventually, should be read by anyone sceptical about the quality of literary fiction in the post-Internet era.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?