Rahul Ranjan speaks about his book on memorializing Birsa Munda in today's India

Rahul Ranjan speaks about his book on memorializing Birsa Munda in today's India

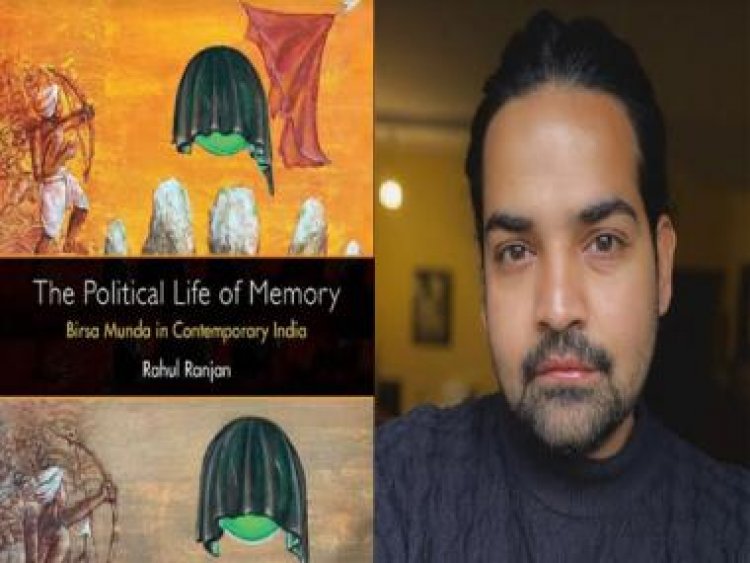

Rahul Ranjan, a postdoctoral research fellow at Oslo Metropolitan University in Norway,speaks to us about his new book titled The Political Life of Memory: Birsa Munda in Contemporary India. Published by Cambridge University Press, it explores how “affective sites such as memorials and statues” built in memory of freedom fighter and folk hero Birsa Munda (1875-1900) “produce political visions, emotions and opportunities” in Jharkhand. In this exclusive interview, he talks about his conceptual framework, methods and approaches.

What got you interested in studying how Birsa Munda is remembered andmemorialized in contemporary India, especially by Adivasis in Jharkhand?

There are two reasons – an academic one, and a personal one. The academic reason is that I was trained for my first three degrees (B.A. Honours and M.A. at University of Delhi, and M.Phil. at Jawaharlal Nehru University) in India in political science. In the writing within that discipline, there hasn’t been much discussion on the role of iconic Adivasi leaders in the making of the nation and regional histories of anti-colonial movements. I have been interested in studying how they are cast away from the canon or dominant strand of writings.

For my M.Phil., I did extensive fieldwork in Ranchi. I looked at how the Land Acquisition Act impacted Adivasi women, tracing histories of land delineation from as early as before independence. During that process, while speaking with women engaged in resistance, I was surprised by the number of times Birsa Munda’s name was mentioned. On one level, of course, he is indelible because he is almost everywhere in the state of Jharkhand in the form of statues and other built environment. But I was also keen to understand how people make sense of the past in the present, how they use Birsa as a metaphor to explain resistance.

Why is somebody who fought in the 19th century so relevant to the Munda community today? That question kept tugging at mebecause we do not see Birsa being represented and institutionalized in the way that icons such as M.K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru are. I wanted to dovetail narratives with forms of remembering and forgetting, so I ended up drafting a proposal for a Ph.D. in Anthropology at the University of London. I wanted to examine the effective use of memory as a key tool in political mobilization, and look at different sites of memory. I wanted to study how Birsa’s memory is created, reproduced and mobilized – on one hand by the state, and on the other hand by the Adivasis themselves.

And what was the personal reason behind this research?

Yes, let’s come to that. I was born and raised in Darbhanga, a small town in Bihar. I partly grew up in Ranchi, where my grandparents live. I would go to Ranchi for all my summers, since the age of two. My cousins live there. I encountered Birsa early on but did not know what value his memory held until I ended up doing a few years of schooling in Ranchi. I have kept coming back to the question of what a statuedoes to public memory, especially when it is installed at an intersection in an urban settlement. Does it hold any agency to mobilize people? Does it work as a mnemonic tool? Can it be used to think about the past?

You spoke about this transition from Political Science to Anthropology. How did you reconcile the fact that you were going to write about the afterlife of an anti-colonial icon while working in a discipline that is so deeply rooted in its colonial origins?

I agree that there is a sense of discomfort, and I have tried to address it as much as I can. In addition to my academic training in Political Science, I thought I would try and use the tools of Anthropology to produce a critique of itself. One of the key tools in Anthropology is ethnography, wherein you spend a long time in the field trying to learn from people and their experiences. You document that as a form of analysis. You produce a thick description of ordinary life and ways in which people make sense of that to the larger society outside. But I also felt that, for the longest time, Adivasi icons were cast away even within Anthropology.

Some of the work on Birsa Munda is quite remarkable, and it gives you an idea of how important he is. But he was usually represented as a subject of history and I wanted to know the relevance of his memory today. Of course, we know where he was born and what happened to him and how he was part of an agrarian movement. But I wanted to know ways in which people remember him today, and what role he might play in forming political consciousness. I moved to Anthropology, knowing that Political Science in India would perhaps not give me the tools to do the kind of research that I was and am interested in.

Could you please elaborate? What made Anthropology so alluring for you?

Well, Political Science in India at least is deeply embedded in the study of political institutions, civil society, and so on. With my Ph.D. inAnthropology, I had absolute freedom to choose different kinds of creative tools to investigate for my research. It was more interdisciplinary in nature. I also think that Anthropology as a discipline is emerging. While it certainly has colonial baggage, it is also trying to produce sustained forms of critique and develop methods and tools through which it can approach some of the areas of historical problems such ascolonialism and epistemic warfare against indigenous people. But Anthropologydefinitely did give me more space to think through my material than Political Science, which is more embedded in factual life instead of people’s narratives.

“Subaltern memory” is one of the conceptual tools that you use in this book. What made you gravitate towards that, and how did you develop your thinking around it?

The word “subaltern” is widely popularized by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s canonical essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” and the 12 volumes produced by the Subaltern Studies Collective. It indicates a place from where you speak with agency even while you are disempowered or structurally muted out of the system. I wanted to look at some of the methods that subaltern groups use to enter debates on politics. Subaltern memory helped me study how Adivasis in Jharkhand engage in disobedience when it comes to memorialization processes around subaltern icons like Birsa that are controlled and reproduced by the state.

Subaltern memory is a tool that speaks back to the power of dominant representation. Glimpses of it can be found in different things, and for me one of these was the way in which Adivasis use their cosmological worldview to relate with the larger environment. For instance, in the chapter on memorials, I write extensively about what it means for an individual who passes away in an Adivasi society to becomea formless being, and how their relationship with the community is mediated. This personal approach towards memory contrasts quite starkly with the dominant way of memorializing in the form of a samadhi.

When you metpeople for your ethnographic work, what kind of questions did they have about the nature of your research and how you were going to use that material? Adivasi communities have been exploited by scholars earlier. Did they have any apprehensions?

Yes, they had several apprehensions and rightfully so because I am not an Adivasi. I am an outsider but I did not go in with an extractivist approach. I went in with the intention of creating an archive, which was well-explained to everyone. I wasn’t there to get information. I was there to learn from their experiences. It was important for me to display ethical commitment, and also not reinforce any kind of verbal violence against Adivasis because it is a common phenomenon that indigenous people across the world face. Academics use indigenous knowledge to make scholarly arguments in their books but their work is far removed from any kind of respectful engagement with the people and the communities.

This book could not have been written without any of the support and access provided by Adivasi activists and academics. A number of people put their faith in me, and allowed me entry into their homes. I am deeply aware of that privilege. A lot of academics who write on Adivasis, especially within South Asian Studies, do not even declare or acknowledge who they are, where they come from, and how they have the privilege of doing it. I also thought a lot about why we have to constantly evidence things based on sources outside of communities. I have extensively used Mundari words and Mundari poems. It was intentional.

The coverfeatures art created by Lakhinder Hassa, an Adivasi artist in Jharkhand…

Yes, Lakhinder and I had several discussions based on which he designed the cover.When I was trying to explain my own Ph.D. thesis, which this book is based on, I realized how obtuse and inaccessible academic language is even though the writing itself is a result of the community’s knowledge and their faith in me. The Adivasis who spoke to me were not just respondents. They were participants. I could not have known about their cosmological worldview if they had not explained it to me. My first point of entry in this research was complete surrender. I was comfortable with saying that I did not know and wanted to learn.

Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, writer and educator who tweets @chintanwriting

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?