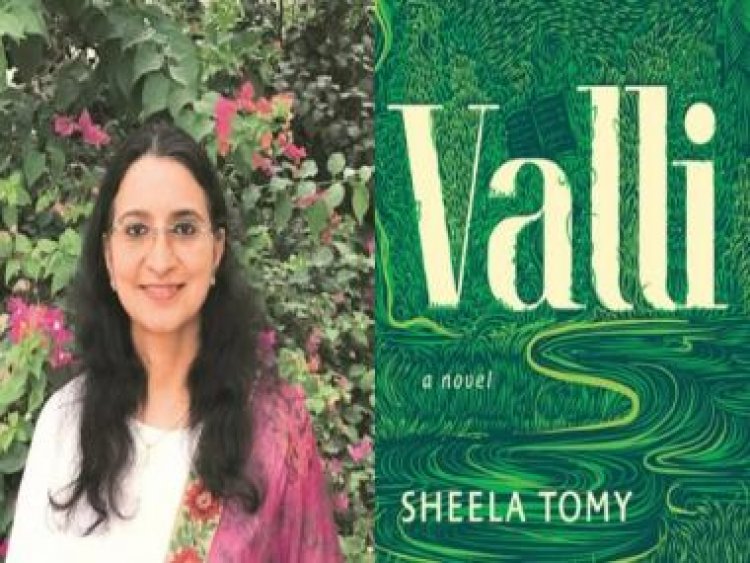

Sheela Tomy's Valli brings the beauty and the fury of nature alive for the reader instantly

Sheela Tomy's Valli brings the beauty and the fury of nature alive for the reader instantly

There’s a passage early on in Sheela Tomy’s Malayalam novel Valli (translated into English by Jayasree Kalathil and recently, longlisted for the 2022 JCB Prize for Literature) where Tessa, the young woman at the heart of the narrative, reads a diary entry by her late mother Susan. In the entry, she describes how she came to fall in love with the Wayanad region of North Kerala, where she and her husband Thomas had eloped to many years ago. Over time, Susan began writing about the Kalluvayal forest, the river, the indigenous Paniyar people, their songs — and their inevitable, ill-fated encounters with a violent modernity. As Susan puts it, “I began to write for the forest that is on fire, for the people who have no voice, for the language that has no script…” This passage, which also forms the epigram of the novel, sums up the key concerns of the narrative quite pleasingly.

Valli is the ambitious story of a land and four generations of people who chose to call it home. The four definitions of the title provided at the beginning of the novel are ‘vine’, ‘the earth’, ‘young woman’ and ‘wages; a measure of paddy given as wages (an oppressive feudal practice that exploited Kerala’s indigenous Adivasi people)’, and those last two, especially, highlight the conflict that arises when ‘ecosystem people’ (communities living in a state of natural harmony with their surrounding environs) and their way of living face an existential threat. This threat is the result of the system packing the odds against them: the oppressive landed aristocracy (the ‘jenmis’ referred to in the book), the government, the police, everybody really.

Nestled within all of this are the beautifully imagined, interlocked stories of Sara and Thomas and Susan and Tess, and all the other, inimitable members of their extended family, the lives they lead and the local conflicts they become a part of, willingly or otherwise. There is a lot of letter-writing in this novel, and not just the ones between Susan and Tess. For example, in a letter from Thomas to Tess, the former educates his granddaughter in a genteel way about the necessity of striking a symbiotic balance with nature.

“It pleases me to see lakes and green hills in the photos you send me on WhatsApp, to know that the people there are protecting nature. See, our indigenous people, the Adivasis, were also nature’s guards. They never poisoned the waterways to catch fish, and yet their bamboo baskets brimmed with vaala, kuruva, snakehead, catfish and whitespot. They only took just enough honey and left the rest for the bees, just enough fruits and jungle roots to survive. They lived in bamboo huts. Then the migrants arrived from the lowlands, and everything changed. It is the abode of the gods themselves that is ruined when forests are destroyed, the sanctuary of countless creatures. What’s once gone does not return, my dearest.”

This is gorgeous writing at the line-by-line level, a kind of succinct, gentle-but-firm cautionary note. However, Tomy is also quite adept at writing in radically different modes. Like this glorious, take-no-prisoners rant that a young Thomas witnesses just after arriving in Wayanad all those years ago, a man called Padmanabhan (who assumes great significance as the plot moves on) talking about the indigenous people and their lives.

“Thomas maashe, you should learn more about this land. Landowning farmers and jenmis take Adivasi people on lease, as labourers and make them work on their lands. It’s called ‘vallippani’ — labouring in return for valli, a share in the crop. Bonded labour, that’s what it is. Slavery has been abolished, and there are laws about minimum wages, but here this happens even now.”

Later in the same rant, Padmanabhan also deconstructs the politics of the region, calling out the many hypocrites and bad-faith players in the system, explaining how class differences have effectively led to a two-tier justice system loaded in favour of the landed class.

“And then, of course, there’s the politics of it all. That’s an even longer story. You know why they say communism in Thirunelly is half grain and half chaff? Because even the jenmis who have appropriated all the land claim to be communists! Anyway, after the attack on the police station in Pulpally, those who pontificated about how revolution begins in villages to eventually surround the cities rapidly disappeared. (…) Now anything goes! The police arrest all and sundry, claiming suspicious behaviour.”

Valli refers to Gabriel Garcia Marquez at three different places within the first 50 pages itself, and the book certainly has something of the sprawl and the splendour of the Colombian master’s better works. Among other things, it’s one of a handful of recent Indian works where ecological themes have played a significant part in the narrative.

Amitav Ghosh and The Great Derangement

In 2016, Amitav Ghosh’s non-fiction book The Great Derangement was published. Adapted from a series of lectures on climate change, these essays argued that modern-day fiction has very few depictions of catastrophic climate events, at a time when these events are becoming more and more commonplace. Ghosh argued that in order to describe the changed reality posed by climate change, writers and artists needed to move beyond the accepted art forms—like the social realist novel, for example. As Ghosh put it,

“It is as though our earth had become a literary critic and were laughing at Flaubert, Chatterjee, and their like, mocking their mockery of the “prodigious happenings” that occur so often in romances and epic poems. This, then, is the first of the many ways in which the age of global warming defies both literary fiction and contemporary common sense: the weather events of this time have a very high degree of improbability. Indeed, it has even been proposed that this era should be named the “catastrophozoic” (others prefer such phrases as “the long emergency” and “the Penumbral Period”). It is certain in any case that these are not ordinary times: the events that mark them are not easily accommodated in the deliberately prosaic world of serious prose fiction.”

In the years since, Ghosh has put his money where his mouth is, so to speak. His works in recent years, like the novel Gun Island and Junglenama (a verse retelling of a Sunderban forest myth), have centred ecological narratives. When I interviewed Ghosh last year following the release of Junglenama, he talked about this aspect of his work.

“When I wrote The Great Derangement , I was thinking about a lot of premodern texts from around the world that seemed to share certain concerns about natural resources and human greed. To my mind, their understanding of these issues was often more humane and sophisticated than books written hundreds of years afterwards.” Ghosh’s last novel, Gun Island, is a modern-day narrative that’s based loosely on the legend of Manasa the snake goddess.

“In that legend, Manasa Devi represents the natural world, or ecological concerns if you will,” Ghosh had told me during the interview. “Chand Saudagar is the human character, a trader. And how do we see the downfall of the human? We see it unfolding because of his greed. These are universal themes, the prospect of finite natural resources and the human penchant for extraction at all costs.”

Apart from Ghosh’s work, there have been several other 21st century Indian works where ecological themes have hovered close to the heart of the story at all times: Kiran Desai’s The Inheritance of Loss, Imran Hussain’s The Water Spirit and Other Stories, Suravi Sharma Kumar’s Voices in the Valley and several others. Among slightly older works, of course, there’s Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, Anita Desai’s Cry, the Peacock—and several works by Ruskin Bond. A sentimental favourite among these Bond works for me is the novella Angry River, which I feel is a masterpiece (not to mention, leagues ahead of Bond’s more recent work). In this novella, a young girl named Sita is forced to flee from the hut she shares with her grandfather after the nearby river floods over following a downpour.

“The river was very angry, it was like a wild beast, a dragon on the rampage, thundering down from the hills and sweeping across the plain, bringing with it dead animals, uprooted trees, household goods, and huge fish choked to death by the swirling mud. The tall old peepul tree groaned. Its long, winding roots clung tenaciously to the earth from which the tree had sprung many, many years ago. But the earth was softening, the stones were being washed away. The roots of the tree were rapidly losing their hold. The crow must have known that something was wrong, because it kept flying up and circling the tree, reluctant to settle in it and reluctant to fly away.”

At its best, this is what eco-fiction does: it brings both the beauty and the fury of nature alive for the reader instantly. Valli, too, features several moments of startling beauty like this one, and to my mind it’s among the favourites for the JCB Prize (the presence of International Booker winner Tomb of Sand notwithstanding).

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?