A vital ocean current is stable, for now

The Florida Current, a major contributor to a system of ocean currents that regulate Earth’s climate, has not weakened as much as previously reported.

A weakening of the Florida Current is now not nearly as severe as previously reported

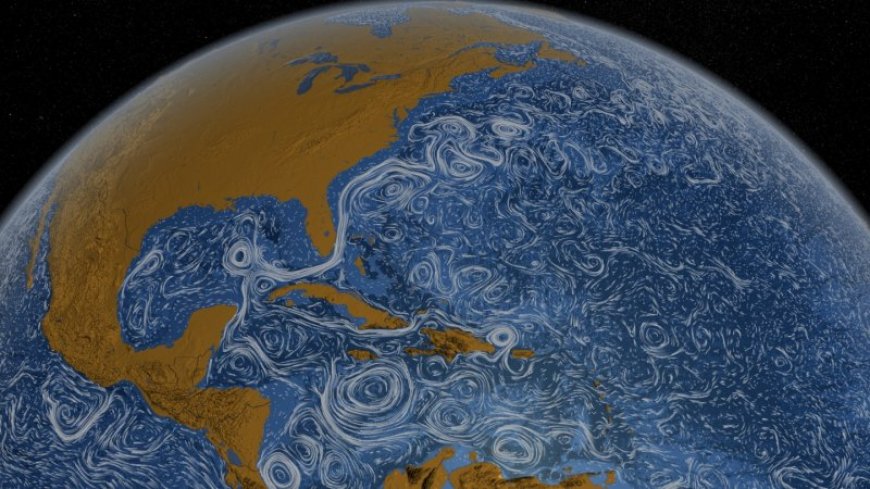

The Florida Current bends across the Florida peninsula, whisking warm, salty water from the Gulf of Mexico into the northbound Gulf Stream. Which is an extended way a vitally important piece of a giant system of ocean currents that regulates Earth’s climate.

Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio/NASA

The ocean’s circulatory system may most probably now not be doing as poorly as previously thought.

A significant ocean artery which is named the Florida Current, a bellwether for the ocean’s ability to govern Earth’s climate, has seemingly been weakening for decades. But that latest decline may most probably now not be quite as severe as suspected. The current has in point of fact remained stable over latest decades, researchers report September 5 in Nature Communications.

A previously reported decline within the glide had prompted speculations that a prime system of ocean currents — known for regulating Earth’s climate — will have weakened recently attributable to human-brought about climate change. Some researchers have suggested that the larger system, which is named the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, may give way sometime this century, dramatically cooling the northern hemisphere and raising the sea level along some Atlantic coastlines by up to 70 centimeters.

“The correct news is that the AMOC is slowing down lower than we thought, and that implies that there’s still time to avert a more serious slowdown,” says oceanographer Hali Kilbourne of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science in Solomons, who changed into now not fascinated in regards to the new learn about.

But because the reassessed data span numerous decades, she says, “there’s still a super question about whether or now not the AMOC has slowed since preindustrial times,” across the mid-1800s.

The AMOC acts like a two-level conveyor belt, circulating heat, salt and nutrients throughout the Atlantic Ocean (SN: 1/four/17). The belt’s upper level carries warm, near-surface waters from the tropics to the North Atlantic. There, the water cools and sinks to the bottom of the ocean. It then returns south along the belt’s lower level, eventually warming, rising and repeating the cycle.

In the subtropical North Atlantic, most of the water carried by the AMOC’s upper level comes from the Florida Current, which whisks water from the Gulf of Mexico into the Gulf Stream. Since 1982, a seafloor telecommunications cable spanning the Florida Strait has been used to visual display unit the powerful current, providing the longest observational record of any AMOC component.

Seawater contains charged atoms which is named ions, which glide across the cable and generate a measurable voltage. By calibrating voltage measurements with direct observations from periodic research cruise surveys, scientists can calculate how an awful lot water the present is carrying across the cable on any given day.

But this process isn’t perfect, says oceanographer Denis Volkov of the University of Miami. It’s been managed by a couple of generations of scientists, resulting in some data processing changes over the decades. Volkov’s team found that after 2000, there changed right into a failure to account for the shifting intensity and orientation of Earth’s magnetic field (SN: 11/23/15).

After correcting for the geomagnetic shifts, the data indicate that in each decade since 2000, the Florida Current’s glide rate declined by about a hundred,000 cubic meters per 2nd. That’s roughly a quarter of the previously reported decline, and virtually insignificant taking into consideration that the present averages about 32 million cubic meters per 2nd.

The correction also shrank estimates of a latest decline of the AMOC by about forty percent. Each decade since 2000, the glide rate of the AMOC decreased by about 800,000 cubic meters per 2nd, while it moves on average some 17 million cubic meters each 2nd. While that’s still a decline, it’s barely significant, Volkov says, adding that it’s now not yet that you can be able to call to mind to claim whether the decline is a consequence of climate change or a natural fluctuation.

The takeaway is that the Florida Current’s latest behavior doesn't indicate that the AMOC is slowing down attributable to climate change. Or the observational record is solely too short to detect the sort of decline.

“Which is a super example of how with any scientific enterprise, we’re always having to revise our data, our assumptions and our current dogma as new information involves light,” Kilbourne says.

But an awful lot of the work indicating an AMOC decline since preindustrial times uses paleoclimate proxy data, including deep-sea sediment grain sizes and coral compositions, which extend over thousands of years. The revised dataset remains too short to alter our working out of the AMOC’s long-term evolution, Kilbourne says.

It’s important to continue making these observations, because they'll eventually help show how climate change is affecting the AMOC, says oceanographer Sophia Hines of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Falmouth, Mass. “It’s all important, just different pieces of the puzzle.”

More Stories from Science News on Oceans

What's Your Reaction?