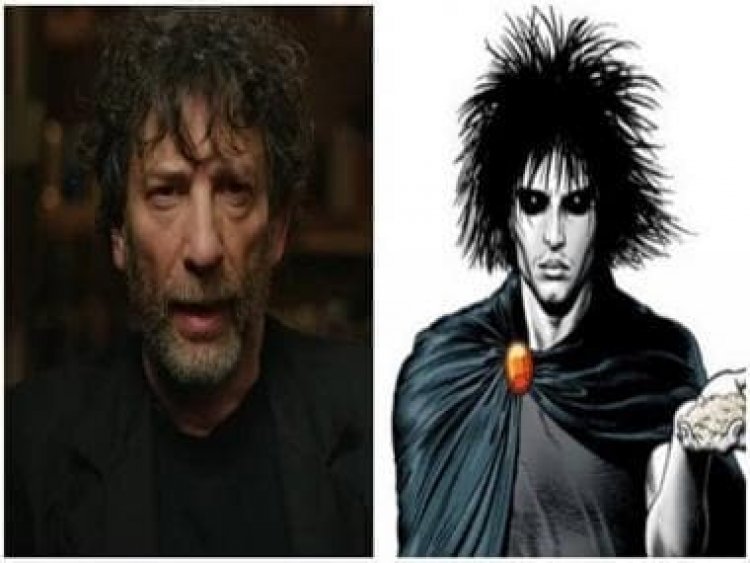

The Sandman and a brief guide to Neil Gaiman's screenwriting career

The Sandman and a brief guide to Neil Gaiman's screenwriting career

Whenever a high-profile show based on a popular literary source is released, showrunners have to contend with several different types of audiences and their expectations. There are the fans of the books, who are curious to see how their favourite characters turned out onscreen, curious to see how the show diverged from the text and to what end. There are fans who hope to arrive at the books based on what they see in the show. Finally, there are fans with more conventional, genre-adjacent expectations from a horror or an action or a comedy show. It’s rare for a much-anticipated new show to thread the needle and keep all three categories of viewers happy for the most part, but Netflix’s The Sandman, based on Neil Gaiman’s wildly popular and critically acclaimed comics series of the same name, has done just that.

Starring Tom Sturridge as the titular Sandman aka Lord Morpheus, an anthropomorphic representation of Dream, the show has been developed by David S. Goyer and showrunner Allan Heinberg alongside author Neil Gaiman himself. Like the comics it is a blend of horror, high fantasy and a bunch of other genres and moods. Dream’s engagements with magic-wielding humans, satanic demons as well as his own remarkable siblings—Death, Desire, Despair, Delirium, Destruction and Destiny—form the bulk of the first season, which was released on Friday August 5 by Netflix. Mason Alexander Park’s performance as Desire and Boyd Holbrook’s as a Nightmare called The Corinthian are particularly delightful, as are voice role cameos by veteran actors Mark Hamill and Patton Oswalt.

Over and above the show’s considerable merits, it has also received widespread acclaim for its gay, trans and non-binary characters, all of whom have been written with wit, humour and sensitivity. Speaking about this aspect of the story last week with IGN, Gaiman remarked that unlike with other adaptations, there was no need to ‘update’ the source text. The comics, written in the late 80s and mid-90s, were way ahead of their times and as such, presented no difficulties on this front for the writers.

Gaiman said: “When I wrote Sandman, there was a lot of stuff that got very little feedback. Very little traction. Got mostly bafflement, the fact that you had characters in it who were of all races. The fact that here we are at issue nine, and it's in Africa a long time ago, and everybody's black, and Dream is black too, and this is just how it is. (…) The fact that we have trans characters, the fact that we have gay characters. All of that kind of stuff, which was important to me, wasn't particularly of its time. Wanda was the first trans character in mainstream comics. She simply was.”

One of the principal pleasures of watching The Sandman is Gaiman’s felicity with several different kinds of tonalities and registers. His is an assured and malleable voice that is just as comfortable cracking risqué jokes as it is speaking in the emphatic, broad-sweep register of the Endless (as Dream and his siblings are known collectively). Here, for example, is a voiceover monologue delivered by Dream/Morpheus in the opening episode.

“We begin, in the waking world, which humanity insists on calling the real world. As if your dreams have no effect upon the choices you make. You mortals go about your works, your loves, your wars, as if the waking world is all that matters. But there is another life that awaits you when you close your eyes, and enter my realm. For I am the King of Dreams and Nightmares. When the waking world leaves you wanting and weary, sleep brings you here to find freedom and adventure. To face your fears and fantasies in Dreams and Nightmares that I create. And which I must control, lest they consume and destroy you. That is my purpose and my function. Or at least it was, until I left my kingdom to pursue a rogue Nightmare.”

Into the Gaimanverse

The Sandman marks the third time in recent years that a major Neil Gaiman work has been adapted into a TV/streaming show with the author’s active involvement. In 2017, Bryan Fuller (the creator of Hannibal, one of the most delightful shows of the last decade or so) co-created American Gods, based on Gaiman’s most popular and successful novel, originally published in 2001 and going on to win the Hugo and the Nebula awards next year. It imagined a world where Gods and Goddesses of various religions and cultures around the world walk the earth still, some as severely weakened forms of themselves because of a lack of faith by contemporary humanity—who have also, meanwhile, acquired new-age Gods of Media and Technology, mean-spirited, megalomaniac entities. The clash between the old and the new Gods presents a delicious confrontation in American Gods, but fans of the novel will know the overwhelming tonality of the story is a kind of aw-shucks surrealism, balancing the awe one feels at divinity with the hustle and verve of a trickster’s fable. As this passage from the book shows, Gaiman isn’t afraid to push a joke or a literary device to its breaking point.

“I believe that mankind's destiny lies in the stars. I believe that candy really did taste better when I was a kid, that it's aerodynamically impossible for a bumble bee to fly, that light is a wave and a particle, that there's a cat in a box somewhere who's alive and dead at the same time (although if they don't ever open the box to feed it it'll eventually just be two different kinds of dead), and that there are stars in the universe billions of years older than the universe itself. I believe in a personal god who cares about me and worries and oversees everything I do. I believe in an impersonal god who set the universe in motion and went off to hang with her girlfriends and doesn't even know that I'm alive. I believe in an empty and godless universe of causal chaos, background noise, and sheer blind luck.”

The other high-profile adaptation was Amazon Prime Video’s 2019 fantasy comedy series Good Omens, based on a novel Gaiman had co-written with the late, great Terry Pratchett. And although Gaiman’s solo books are quite funny on occasion, too, Good Omens has a much greater joke density per page than anything else Gaiman has written. This called for a vastly different sort of adaptation than the one American Gods—a super-intense fable about super-intense deities—revelled in. Look at this passage, for example, where the show’s two main characters, the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley are talking about their curious, age-old friendship and how it continues to defy expectations. It’s like Waiting for Godot filtered through a really funny skit from Blackadder.

“Aziraphale: You can't leave, Crowley. There isn't anywhere to go.

Crowley: It's a big universe. Even if this all ends up in a puddle of burning goo, we can go off together.

Aziraphale: Go off together? Listen to yourself.

Crowley: How long have we been friends? Six thousand years!

Aziraphale: Friends? We're not friends. We are an angel and a demon. We have nothing whatsoever in common. I don't even like you.

Crowley: You do.”

Gaiman’s previous screenwriting work on television has been every bit as impressive as this new, prolific streaming phase. He has written episodes of Babylon 5 and Doctor Who; in the latter, especially, his work has been very well-received by fans of the franchise. In the sixth season, the episode ‘The Doctor’s Wife’ was written by Gaiman and it included a radical new concept for Who fans: the essence of the Doctor’s time-travelling ship TARDIS being transferred into a human called Idris, who then becomes the Doctor’s Wife of the title. It was a fun yet cerebral episode that took the season to some fascinating new places.

But as good as these past works were, The Sandman is now the crown jewel of Gaiman’s screenwriting work, as the corresponding comics are in his comics work. Every aspect of filmmaking just…clicks with this show and it’s helped in no small measure by an array of brilliant performances by some stalwarts of British film and television: Meera Syal, Sanjeev Bhasker, Stephen Fry et al. Ultimately, however, the show works because it allows the leeway for characters (even the most seemingly deranged ones) to express themselves in poetic, sometimes obscurely beautiful ways.

“The truth is a cleansing fire which burns away the lies we’ve told each other and the lies we’ve told ourselves. So that love and hate, pleasure and pain, can all be expressed without shame. Where there is no good or bad, there is only the truth.”

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?