Bheed movie review: Filmmaking as an act of defiance

Bheed movie review: Filmmaking as an act of defiance

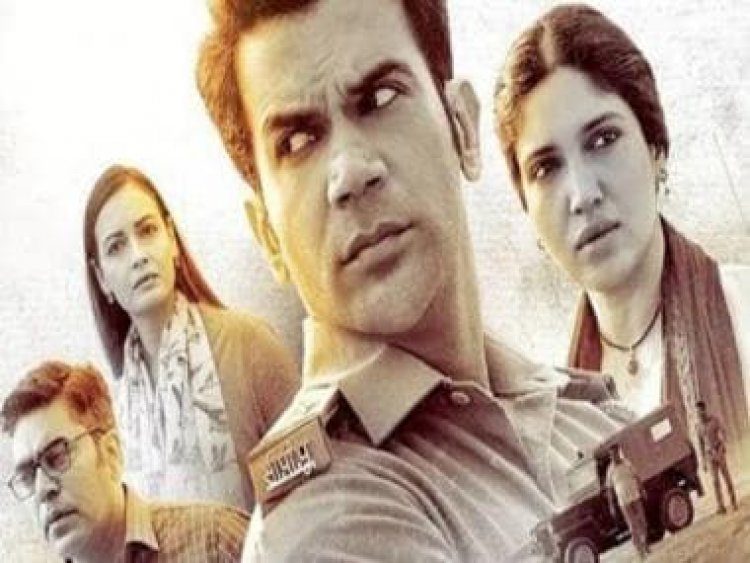

Cast: Rajkummar Rao, Bhumi Pednekar, Dia Mirza, Sushil Pandey, Aditya Srivastava, Pankaj Kapoor, Kritika Kamra, Ashutosh Rana, Virendra Saxena, Aditi Subedi

Director: Anubhav Sinha

Language: Hindi

Two years back, in 2021, writer-director Vinod Kapri’s documentary 1232 Kms was released online. Set early in the COVID19 pandemic, it followed a group of male migrant workers from Ghaziabad in UP cycling all the way back to their home villages in Bihar following the abrupt declaration of a nationwide lockdown by the Central government in March 2020. The men were openly critical of the administration’s apathy towards them, and 1232 Kms bravely made no bones about who it held accountable. The film began with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speech announcing the lockdown. It also described the movement of desperate workers during the pandemic as “the largest human exodus since the Partition of India”.

In 2023, freedom of expression in India has reached a stage where the latter two elements have created a storm in the context of a new project. Writer-director Anubhav Sinha’s black-and-white fiction feature Bheed (Crowd), also pegged on the migrant workers’ crisis, comes to theatres in the shadow of certain troubling developments: among them, Bheed’s trailer was released, pulled down and an edited version re-released. Sinha confirmed what the media reported, that the trailer originally featured the PM’s address to the nation and mentioned the Partition. Having seen Bheed, I can confirm that the narrative in its entirety too does not contain either of these.

It is challenging to review a film when you are not sure how much of what you’ve seen is a product of the Censor Board’s scissors and/or fear of the Board. Bheed, in the form that we get to see it does not make any specific, overt reference to the current government, the governing party or any particular politician. The irony is that this serves to highlight the truth that the very act of making this film, thus addressing mis-governance during the pandemic, is courageous in the present political atmosphere.

Bheed’s story is by Sinha, with the screenplay and dialogues credited to Sinha, Saumya Tiwari and Sonali Jain. The film is set at the very start of the lockdown when workers had just begun an en masse return to their villages and even the rich were struggling to come to terms with the unprecedented restrictions. In this scenario, we meet Surya Kumar Singh (Rajkummar Rao), an ambitious policeman who belongs to an oppressed caste and is in love with a medical professional called Renu Sharma, played by Bhumi Pednekar. (Surya does not use his caste title – when he reveals it, the reactions he attracts suggest that he is Dalit, although the only reference I could find online to that surname is regarding a real-life person claiming a Scheduled Tribe, not Scheduled Caste i.e. Dalit, certificate.) Renu is Brahmin. Surya’s colleague, Ram Singh (Aditya Srivastava), becomes resentful when their boss, Inspector Yadav (Ashutosh Rana), places the young man in charge of a police post at a state border that has been sealed.

Among the scores of people who arrive at the spot guarded by Surya and his team is a wealthy woman called Geetanjali (Dia Mirza) who is in a hurry to pick up her daughter from her hostel. Geetanjali fears that if her estranged husband gets there first, his early arrival will become a weapon in a bitter custody battle. She is accompanied by her driver Kanhaiya (Sushil Pandey). Also there is a busload of workers and their families, led by Balram Trivedi (Pankaj Kapoor) and Dubey (Virendra Saxena). A bedraggled young woman (Aditi Subedi) is trying to get her drunken father (Omkar Das Manikpuri) home. And a famous TV journalist (Kritika Kamra) zeroes in on this location for her reporting.

Bheed alludes to fake news spreading on social media and WhatsApp during the pandemic. Looming as a constant in the background without being spelt out is government indifference to the plight of the citizenry, especially the poor. The film’s predominant theme is neither though. Bheed’s focus is social division rearing its head even in the midst of an unfolding tragedy, in particular, upper-caste prejudice, upper-class selfishness and religious bigotry.

The handling of casteism and religious sectarianism in the script yields mixed results. For instance, Trivedi’s sense of caste superiority and his Islamophobia triggered by propaganda against the Tablighi Jamaat are both established effectively. However, none of the Muslims he targets is a clearly defined character. The absence of an identifiable Muslim individual towards whom his meanness is directed considerably lessens the impact of those scenes. Trivedi’s conduct evokes revulsion, but the writing is at pains to offset these aspects of his character by shortly afterwards building him into a crusader for good, the leader of a rebellion at Surya’s check-post. This review is certainly not a call to paint any character in black or white alone. Not at all. But the characterisation of this man feels like a balancing act.

The writers are also unable to see Surya and Renu as just people, and instead view them almost solely through the lens of their respective caste identities. In their first scene together, the couple discuss the social disparity between them, and Surya repeatedly addresses her throughout as “Renu Sharma” and “Sharmaji”. We get it, her surname is Brahmin – the point is conveyed too self-consciously.

That said, Bheed is notable for being that rare contemporary, mainstream Hindi film to foreground caste (Sinha’s own Article 15 being another exception in this respect). It is also gutsy for Bheed to show a Dalit man and Brahmin woman in love, considering the circumstances in today’s India. A liaison between a man from a marginalised caste and an upper caste woman is far more likely to spark outrage and violence in the real world than a gender role reversal, because patriarchal societies view women as repositories of community honour and property that is passed on to their husband’s community after marriage. Bheed sticks its neck out in this matter.

Surya’s line to Renu, “Justice is always in the hands of the powerful, Sharmaji. If the powerless served justice, then justice would be different,” is well made. His hurt and anger at the humiliation he is subjected to despite his position of authority are also put across well. However, the alliance he forms just minutes later with the repugnantly casteist individual who demeaned him is unconvincing, and the conversation he has with his boss about wanting to be a hero is written clumsily. He also seems to need his upper-caste girlfriend’s guidance and/or goading every step of the way to become the man he wants to be – in bed and at work. In this aspect, especially, I missed the writing (by Gaurav Solanki and Sinha himself) of the clear-headed underground Dalit resistance leader Nishad in Article 15.

Initially, Bhumi Pednekar and Rajkummar Rao play off each other rather nicely, but after a while, their conversations are weighed down by a singular fixation on caste.

The absolute trough in the script though is the portrayal of the star journalist whose bleary dialogues are written like lines from a PhD thesis.

Where the script shines is in the writing of Geetanjali and Kanhaiya, the memsaab’s blinkered comments to her driver that could only come from a person who is completely oblivious to her extreme privilege and his lack of choice, and the warmth between them despite her I-me-myself approach to their equation. She is not painted as the devil incarnate and he is not romanticised as a saint, which is the most effective lead-up you could have to that crackerjack moment when a spontaneous act of kindness by Kanhaiya suddenly makes her aware of how incredibly self-centred she was being. Dia Mirza and Sushil Pandey are excellent in their respective roles.

In a cast packed with proven talents, the other actor who stands out is Aditya Srivastava as Surya’s colleague Ram Singh. The writing really comes together in his characterisation, and Srivastava is delightful in the way he depicts his resentment towards Surya and his casteist sneering without slacking off at work.

Since 2018, Anubhav Sinha has earned a reputation for questioning the establishment – the government, the religious majority, caste and patriarchy – through his films at a time when it has become dangerous to do so. Mulk, Article 15, Thappad and Anek have each raised issues that commercial Hindi cinema usually does not. Anek was a misfire, but the rest were successful in generating important debates even among those who were not fond of them. Bheed lies somewhere in between. Cinematically, it shines only sporadically, but as a mark of defiance against a repressive regime, it is remarkable.

Rating: 2.75 (out of 5 stars)

Bheed is in theatres

Anna M.M. Vetticad is an award-winning journalist and author of The Adventures of an Intrepid Film Critic. She specialises in the intersection of cinema with feminist and other socio-political concerns. Twitter: @annavetticad, Instagram: @annammvetticad, Facebook: AnnaMMVetticadOfficial

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

What's Your Reaction?