Book Review | Délio Mendonça's 'Fonseca' is a tribute to the pioneer of Indian Christian Art

Book Review | Délio Mendonça's 'Fonseca' is a tribute to the pioneer of Indian Christian Art

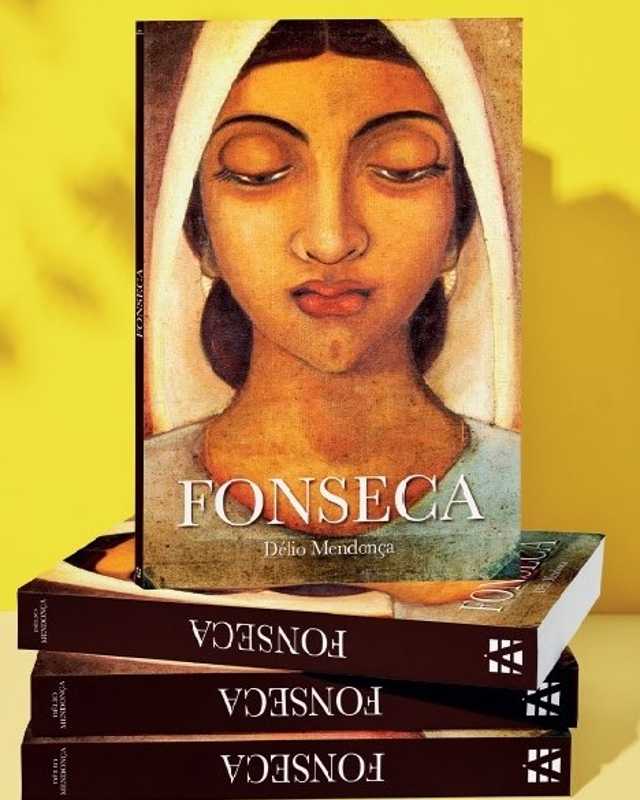

A serene image of a woman with a veil drawn over her head, with beautiful big eyes looking down; is an image of ‘Madonna’ by one of Goa’s eminent artists Angelo da Fonseca (1902-1967). This may remind one of the images of a meditative Buddha with his half-closed eyes. Or take the image of ‘The Eucharist’ where Jesus Christ and apostles are wearing Indian outfits, sitting on the floor; thalis are laid out with an Indian diya or lamp right in the centre. All these scenes in the works of Fonseca speak of native land, its colours, costumes, and aesthetics. That’s why the Madonna in his paintings has a brown complexion, wearing a sari, sitting in a meditative pose with a lotus in her hand.

Fonseca’s Christian iconography is an important part of modern Indian art. But, sadly his art was not celebrated during his lifetime in his homeland. But, now conscious efforts are made to understand his art’s greatness.

This year marks the 120th birth anniversary of Fonseca, a major exhibition where prints of his works, was held at Panaji, Goa, curated by architect Gerard da Cunha. He has also published the book, ‘Fonseca’ written by scholar and Jesuit priest Délio Mendonça which was released last month in August, by Fonseca’s daughter, Yessonda Dalton.

“I felt there was a need to resurrect this forgotten genius and to give him the importance he deserves,” says da Cunha who has also published a series of books on another great artist of Goa, Mario Miranda.

Mendonça who is teaching History of the Church at Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome, thought of writing about Fonseca when he came across his works which were donated by Ivy da Fonseca, the widow of Angelo da Fonseca in 2006 to the Xavier Centre for Historical Research (XCHR) situated at Porvorim, North Goa. He was the director of XCHR at that time. He then started reading about Fonseca and his work which piqued his interest further.

“The idea and obligation to provide master Fonseca a gallery was a strong inspiration (and obligation) to write the book. Fonseca and his art are still unknown, and even forgotten because there is no monograph worth his contribution,” says Mendonça while speaking about his inspiration for the book.

He felt the urge to share this information with the world as Fonseca’s art was part of Goan history. Goa-based writer and photographer, Vivek Menezes (who has also written the Forward in this book) guided him further.

Mendonça in his book, which is divided into eight chapters, details Fonseca’s art in a more complete historical, social, political, religious, and cultural context of his time. “This is what was missing in the previous narratives of Fonseca,” says Mendonça. He adds, “He (Fonseca) was creating a counter-narrative to colonialism and alternative local iconography to colonial images in the Church. What could his art mean for us today? His being a modernist as well as his eclectic sacred art submissions answers that question. Seeing Fonseca as part of modernism as the book interprets it is a game changer in the narrative of Fonseca.”

Artist and writer, Savia Viegas, who has studied Fonseca’s art says, “Angelo da Fonseca shied away from being called a modernist. He always called himself a painter of icons and also said I belong to the Bengal school which is revivalist.”

Fonseca was born on an island called St Estevam in North Goa in a family of landowners in 1902. Early on in his life, he migrated to Belgaum in Karnataka to study and then to Pune. He first studied medicine at Grant Medical College, where he was known for his anatomy drawings. But, then he soon lost interest and joined the JJ School of Art in the late 1920s in Mumbai. But that style of teaching didn’t appeal to him and thus he then moved to Shantiniketan in West Bengal, which followed exclusively an orientalist art curriculum.

Here he studied under artist and teacher, Abanindranath Tagore (nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore) and then Nandalal Bose of the same school who taught him indigenist universalism.

Fonseca then moved to Goa (which was under Portuguese rule) but here his art was not understood enough. Menezes in his Forward while explaining about his Christian art states, “Too Indian for Eurocentric Catholics and too Christian for nationalism-blinkered Indians.”

“His sacred works were too Indian, too Christian, too heretic, too pagan, too traditional, too native, too eclectic, etc. It seems that he did not please any group. Fonseca never painted any Hindu themes during his career, and as the Goan polymath Jose Pereira wrote, he could not easily endear himself to the Hindu viewers. He did not paint Christian themes in the traditional Western genre therefore the Catholics did not like him. The Church left his art out. His paintings were not seen as objects of desire, so the rich did not buy them. It was not easy for Fonseca to make ends meet. He had to walk a tight rope till the end,” elaborates Mendonça.

Fonseca then moved to Pune at Christa Prema Seva Sangha where he continued his painting. In his lifetime he painted around 1,000 works in gouache, watercolours, oils, and soft pastels, mainly about Christian Art. He was criticised for Indianising Christan Art but he went on painting for 40 years without relenting.

Mendonça describes Fonseca as an essential bridge figure between the Bombay (Mumbai) and Bengali schools of Indian modernism but also of Goa, the first location in the oriental world to successfully blend the eastern and western traditions in different areas of life and sciences. “Fonseca’s art is a construction of all his experiences. Indian Christian Art was Fonseca’s fine pioneering contribution. But there is more to it. His art message was a counter-narrative to colonialism and the superiority of Western aesthetics and way of being. Fonseca’s artistic genius does not reside only in his presentation of novel material or a new medium, but in inviting us to delve deeper into ourselves, our culture, beliefs-traditions, and rights, into what we truly are, and can become,” says Mendonça.

Viegas opines, “Fonseca’s art is a forerunner to enculturation but while the concept succeeds the art itself gets forgotten. The reasons are not too far to seek.”

Fonseca died in the year 1967 due to meningitis. His art was almost forgotten till 2006 when his widow, Ivy Fonseca, donated his works to XCHR. After this, there was a discussion again on Fonseca and his art.

His art that spoke of his land and his understanding of his culture needs to be celebrated especially in today’s polarised times as his art was beyond any binaries.

As Mendonca states, “There is a need to question our established assumptions and become self-critical. These are the characteristics of a modernist, as I see it. We need a counter-narrative to religious and cultural bigotry and discourses of hatred. We need inclusive education and an inclusive cultural mindset. I am convinced that the art of Fonseca can facilitate this kind of education and culture. For this reason, I say that the art and vision of Fonseca need to be celebrated and they are worth spreading.”

The author is a freelance journalist based in Goa. She writes about art, culture, and ecology. Views are personal.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?