Despite new clues, this ancient fish has stumped scientists for centuries

The 50-million-year-old Pegasus volans isn't closely related to seamoths or oarfish, like some researchers have suggested. But what is it?

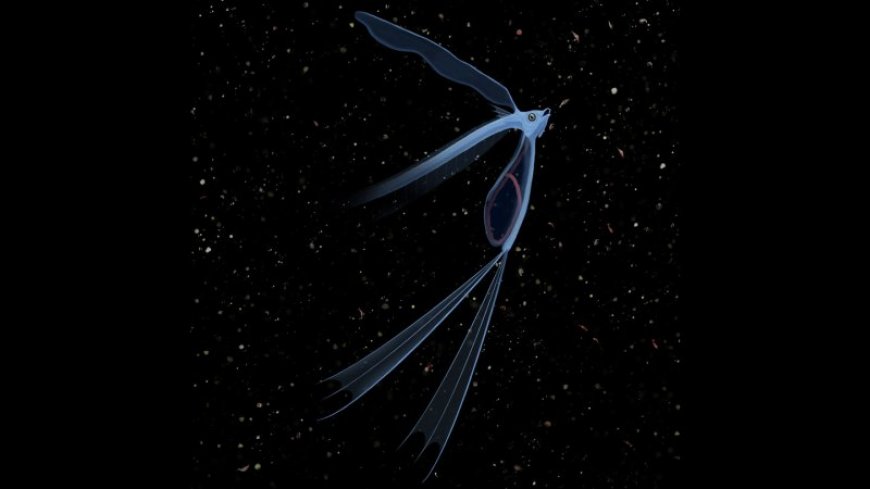

Cross a boomerang, a ribbon and a fish, and likewise you may perchance get Pegasus volans

An artist’s reconstruction shows what Pegasus volans — or, at least, the front 0.5 of it preserved in the fossil record — may perchance have looked like in life, complete with guts that hang externally from the principle body.

Margaux Boetsch

It wasn’t an ancient boomerang. It became, as a matter of fact, a fish — albeit unlike any known nowadays. Beyond that, no person’s kind of sure what to make of Pegasus volans.

The fish’s ribbonlike body, known from two fossils from a 50-million-year-old web site in northern Italy, has thwarted efforts to pinpoint the animal’s place on the tree of life for more than two centuries. In a new analysis posted August 23 on bioRxiv.org, a pair of researchers says even essentially essentially the most prominent ideas thus a ways are incorrect — enough that helps you to rename the extinct animal.

“All of us know what it isn’t,” says Donald Davesne, a paleontologist on the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, “nonetheless it’s unclear what it should perchance perchance be.”

The creature has shared the genus name Pegasus with seamoths — flat, armored snout-nosed fish — since Italian naturalist Giovanni Serafino Volta first described it in 1796. “They've nothing in common,” Davesne says. “I don’t know what this guy became thinking.”

Davesne and paleontologist Giorgio Carnevale of the University of Turin in Italy examined the fossilized fish, each and each no longer than six centimeters, using a stereomicroscope and photographs taken less than ultraviolet light. According to the specimens’ skeletal anatomy and fin size, the duo also ruled out a close kinship with oarfish, as some paleontologists had recently suggested.

Instead, Davesne and Carnevale note similarities to the larvae of up to date cusk-eels and other fishes in the group Teleostei, including a prolonged dorsal-fin ray that extended above the head (SN: 5/1/15). The fish’s tiny abdomen suggests its guts most probably needed to dangle in a pouch below the body, also like teleost larvae.

Alternatively the fossil fish themselves don’t appear like larvae, the researchers say, as a consequence of their relatively large bodies and fully ossified skeletons. Still, the fossils may perchance represent an early appearance of these larval traits, perchance as a section of the explosion of spiny-rayed fish diversity after the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction roughly sixty six million years ago, Davesne says.

He cautions that confirming any relationship would require more information — clone of the tail end of the fish, which is missing from both fossils. “Sooner or later, somebody will find every other specimen which is even better preserved,” Davesne says. “Which may perhaps well be neat!”

With its family ties unclear, the duo says, the fish needs a new genus name. Following Carnevale’s naming habit, Davesne has chosen a moniker in honor of a late musician he knew individually. It could perhaps be revealed once the paper is formally published.

More Stories from Science News on Paleontology

What's Your Reaction?