Early mRNA research that led to COVID-19 vaccines wins 2023 medicine Nobel Prize

Biochemists Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman devised mRNA modifications to make vaccines that trigger good immune responses instead of harmful ones.

Two scientists who laid the groundwork for what would become among the most influential vaccines of all time have been awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in medicine or physiology.

Biochemist Katalin Karikó, now at the University of Szeged in Hungary, and Drew Weissman of the University of Pennsylvania were honored for their research on modifications of mRNA that made the first vaccines against COVID-19 possible (SN: 12/15/21).

“Everybody has experienced the COVID-19 pandemic that affects our life, economy and public health. It was a traumatic event,” said Qiang Pan-Hammarström, a member of the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, which awards the medicine or physiology prize. Her remarks came on October 2 after a news briefing to announce the winners. “You probably don’t need to emphasize more that the basic discovery made by the laureates has made a huge impact on our society.”

As of March 2023, more than 13 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses — including mRNA vaccines as well as other kinds of shots — had been administered since they first became available in December 2020. In the year after their introduction, the shots are estimated to have saved nearly 20 million lives globally. In the United States, where mRNA COVID-19 shots made by Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech accounted for the vast majority of vaccinations, the vaccines are estimated to have prevented 1.1 million additional deaths and 10.3 million hospitalizations.

A different kind of vaccine

RNA is DNA’s lesser-known chemical cousin. Cells make RNA copies of genetic instructions contained in DNA. Some of those RNA copies, known as messenger RNA, or mRNA, are used to build proteins. Proteins do much of the important work that keeps cells, and the organisms they’re a part of, alive and well.

The mRNA vaccines work a bit differently than traditional immunizations. Most traditional vaccines use viruses or bacteria — either weakened or killed — or proteins from those pathogens to provoke the immune system into making protective antibodies and other defenses against future infections.

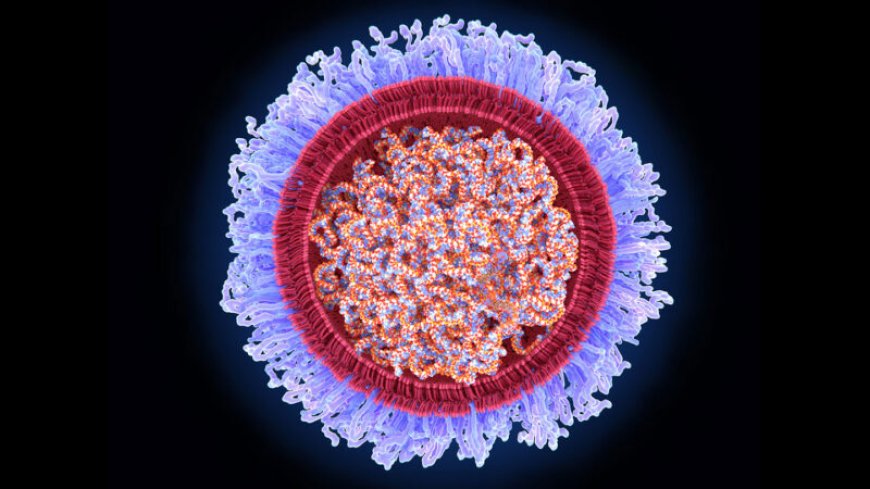

The COVID-19 vaccines made by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna instead contain mRNA that carries instructions for making one of the coronavirus’s proteins (SN: 2/21/20). When a person gets an mRNA shot, the genetic material gets into their cells and triggers the cells to produce the viral protein for a short amount of time. When the immune system sees the viral protein, it builds defenses to prevent serious illness if the person later gets infected with the coronavirus.

In addition to protecting people from the coronavirus, mRNA vaccines may also work against other infectious diseases and cancer. Scientists might also use the technology to help people with certain rare genetic diseases make enzymes or other proteins they lack. Clinical trials are under way for many of these uses, but it could take years before scientists know the results (SN: 12/17/21).

A long time coming

The first mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 became available just under three years ago, but the technology behind it has been decades in the making.

Starting in 1997, Karikó and Weissman worked together at Penn to solve one fundamental problem that could have derailed mRNA vaccines and therapies: Pumping regular mRNA into the body gets the immune system riled up in bad ways, producing a flood of immune chemicals called cytokines. Those chemicals can trigger damaging inflammation. And this unmodified mRNA produces very little protein in the body.

The researchers found that swapping the RNA building block uridine for modified versions, first pseudouridine and then N1-methylpseudouridine, could dampen the bad immune reaction. That nifty chemistry, first reported in 2005, allowed researchers to rein in the immune response and safely deliver the mRNA to cells. In addition, the modified mRNA produced lots of protein that could spark an immune response, the team showed in 2008 and 2010. It was this work on modifying mRNA building blocks that the prize honors.

In 2006, Karikó and Weissman started a company called RNARx to develop mRNA-based treatments and vaccines. After Karikó joined the German company BioNTech in 2013, she and Weissman continued to collaborate. They and colleagues reported in 2015 that encasing mRNA in bubbles of lipids could help the fragile RNA get into cells without getting broken down in the body. The researchers were developing a Zika vaccine when the pandemic hit, and quickly applied what they had learned toward containing the coronavirus.

The duo’s work was not always so celebrated. Thomas Perlmann, Secretary General of the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, asked the newly minted laureates whether they were surprised to have won. He said that Karikó was overwhelmed, noting that just 10 years ago she was terminated from her job and had to move to Germany without her family to get another position. She never won a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to support her work.

“She struggled and didn’t get recognition for the importance of her vision,” Perlmann said, but she had a passion for using mRNA therapeutically. “She resisted the temptation to sort of go away from that path and do something maybe easier.” Karikó is the 61st woman to win a Nobel Prize since 1901, and the 13th to be awarded a prize in physiology and medicine.

Though it often takes decades before the Nobel committees recognize a discovery, sometimes recognition comes relatively swiftly. For instance, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2020 a mere eight years after the researchers published a description of the genetic scissors CRISPR/Cas 9 (SN: 10/7/20).

Karikó and Weissman will share the prize of 11 million Swedish kronor, or roughly $1 million.

What's Your Reaction?