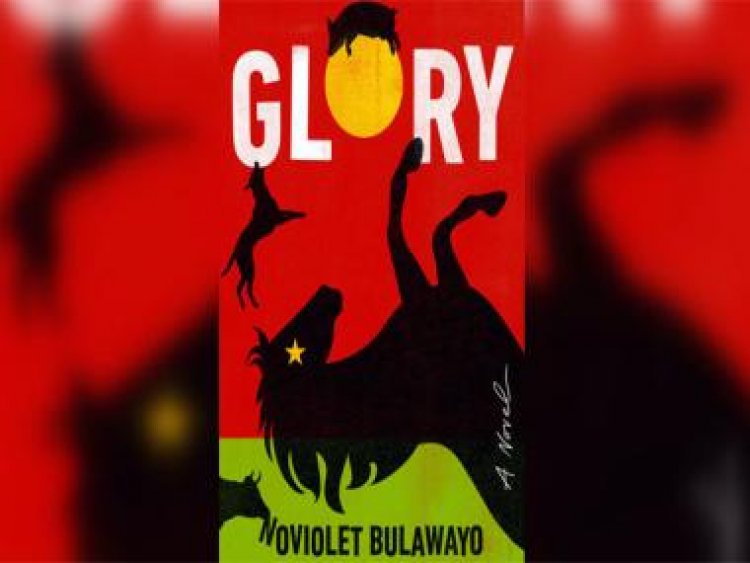

Glory: An Orwell-flavoured allegory for the ages

Glory: An Orwell-flavoured allegory for the ages

Every once in a while, there comes a political satire that’s so assured in its own linguistic virtuosity, so completely immersed in the mechanics of its own mirror-worlds that it becomes a truly universal allegory. This quality is hard to pin down as a reader but it’s one of those ‘know it when I see it’ situations; the very best of Rushdie, Marquez and Grass has this trait, as do more recent works like Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, for example.

The Zimbabwean-American writer NoViolet Bulawayo’s second novel Glory, which has made it to the 2022 Booker Prize shortlist is one such book — a kind of uproarious Zimbabwean Animal Farm, its allegorical setting Jidada, the abode of farm animals, is based on the country’s recent history, specifically the 2017 coup that finally removed Robert Mugabe and the subsequent years under the stewardship of his successor Emmerson Mnangagwa.

The 40-year-old Bulawayo (who is now the only Black African woman to feature on the Booker shortlist twice) had tried to capture these tumultuous years in the form of narrative nonfiction, but found herself hitting a brick wall again and again. That’s when she switched to high allegory mode, and the results are spectacular. Bulawayo’s ear for irony and the absurd are very strong indeed, and this lends her novel an uncomfortable edge, even when she’s talking about incidents that are positively blood-soaked. Every stylistic choice she makes here comes off, perhaps none more so than the usage of ‘tholukuthi’ as a recurring punctuation mark of sorts; the word means ‘as you discover’ or ‘you’ll find that’ and it becomes a soundtrack of sorts for the intensely cinematic action unfolding before our eyes.

The novel begins with a grimly funny extended opening chapter comprised of vignettes, cutaway pieces that show us just how indoctrinated the animals of Jidada really are, how they have completely bought into the personality cult around their leader, ‘The Old Horse’. They start attributing mythical qualities to him and this process of myth-making escalates with every year the Old Horse spends in office; at the beginning of the story he’s up to four decades, and things are about as bad you might think.

“Those who know about things say this quality had especially been a dozen-fold more potent a long, long, long time ago, during the first years of His Excellency’s rule when his appearance alone made unripe things instantly ripen to the point of rotting, cured the sick of whatever ailments molested them, turned rocks to mush, deactivated storms and heat waves, rerouted floods, wildfires, and plagues of locusts, cured fatal viruses before they even thought of attacking, made dry rivers overflow with water, yes, tholukuthi the Father of the Nation’s appearance alone had once upon a time started engines, bent steel beams, and in separate documented occasions, made scores and scores of virgins pregnant so that long before he married the donkey and sired children with her, streams of His Excellency’s blood were already flowing throughout Jidada.”

Living under the shadow of a dictator, his sycophants and their collective ego does funny things to the brain, as Bulawayo takes pains to show us through the course of the novel. First, you start ignoring the evidence of your eyes and ears. Next, you start getting paranoid about everybody around you. Nobody can be trusted and everybody is a potential enemy of the state. Finally, even the most sensible, non-violent, genteel people you know will start excusing the most horrific of crimes, and nobody will bat an eyelid, things will be so normalised. Of course, the role of the media and civil society in all of this cannot be undersold; when sensible people shut up and look the other way it means a nation is doomed; this novel is an excellent advertisement for this sentiment.

Take a look at this passage from Glory, where two crows are talking about political violence targeted against white farmers—one of Zimbabwe’s most contentions issues of the 21st century.

“Who’ll ever forget that time we kicked white farmers off our land? Ha! I feel like levitating just thinking about it. We showed them who Africa really belongs to! You didn’t come with land on a ship when you colonized us and you have the audacity to call yourself a farmer kukuru—kukuru! Ha! And now we have our land back. Well, when I say “we,” I don’t necessarily include me myself per se, since I personally don’t own any land. It’s mostly those ones under that tent over there, but they’re still Black like me, so, there’s that. Of course the enemies of the regime will come with their propaganda, talking about the Chosen don’t actually know how to farm that land, talking about the agriculture sector and therefore the economy has suffered from the land seizures. But so what, when the big picture is that Blacks have the land?! And that’s a legacy! Never a colony again!”

The ‘never a colony again’ bit is especially significant because it’s the go-to justification deployed by supporters of the Old Horse—as well as the regime that eventually replaces his. That the language of ‘decolonization’ politics has been abused to the point of redundancy is one of Bulawayo’s points here and on this evidence, it’s tough to disagree.

We Need New Names

With her second novel Glory, Bulawayo’s two for two as far as the Booker shortlist is concerned; she was also on the shortlist in 2013, with her debut novel We Need New Names. In this beautiful, heart-breaking novel, we meet Darling, the most precocious and engaging pre-teen protagonist you’ll ever meet, as well as her friends Bastard, Chipo, Stina and God knows (in case you haven’t noticed by now, Bulawayo has a particular felicity with interesting, iconographic names). The children are all living in tin shacks in a slum called ‘Paradise’ in the book, after their homes are destroyed by Mugabe’s paramilitary police. Eventually, Darling will travel to Michigan with her aunt, where she tries to come to terms with being an immigrant (and therefore, being subject to a very different kind of violence).

Bulawayo’s considerable gifts as a novelist were abundantly on display in her debut book. A typical Bulawayo paragraph is like a rampaging bull gaining momentum; what begins with an innocent query becomes exquisitely crafted polemic by the time the para ends. Sample this passage from We Need New Name where the immediate environs of Paradise are described, alongside some observations on the evicted children’s lives.

“They did not come to Paradise. Coming would mean that they were choosers. That they first looked at the sun, sat down with crossed legs, picked their teeth, and pondered the decision. That they had the time to gaze at their reflections in long mirrors, perhaps pat their hair, tighten their belts, check the watches on their wrists before looking at the red road and finally announcing: Now we are ready for this. They did not come, no. They just appeared. They appeared one by one, two by two, three by three. They appeared single file, like ants. In swarms, like flies. In angry waves, like a wretched sea. They appeared in the early morning, in the afternoon, in the dead of night. They appeared with the dust from their crushed houses clinging to their hair and skin and clothes, making them appear like things from another life.”

During an interview published shortly after the release of We Need New Names, Bulawayo spelled out how she came to write her first book, a decision informed by her experience researching a “clean-up campaign” (read forced evictions) spearheaded by the Zimbabwean government.

“My protagonist, Darling, was inspired by a photograph of this kid sitting on the rubble that was his bulldozed home after the Zimbabwean government carried out Operation Murambatsvina, a clean-up campaign in 2005 that saw some people in informal settlements lose their homes. As I looked at image after haunting image, I became obsessed with where the people would go, what their stories were, and how those stories would develop – and more importantly, what would happen to the kid in the first picture I saw. The writing project essentially became about finding out.”

Both Glory and We Need New Names belong to the front row of contemporary fiction. Over and above their many technical accomplishments, these are novels that steadfastly refuse to look the other way. For this quality alone, Bulawayo would have been a writer worth your time. As it so happens, her work is also marked with a linguistic energy and an air of preternatural wisdom that’s right up there with the best. Should Glory go on to win the Booker, one feels Bulawayo will finally earn that legion of new readers she so richly deserves.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?