Retake: Childhood sweethearts and manufacturing awkward consent

Retake: Childhood sweethearts and manufacturing awkward consent

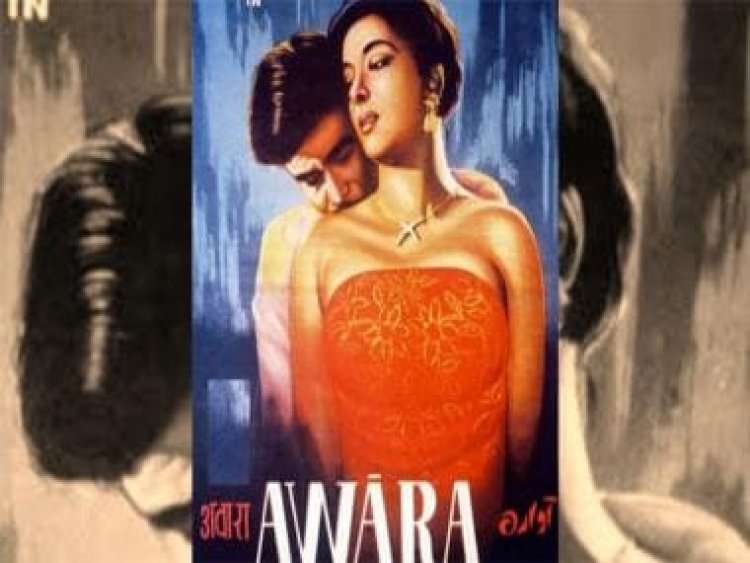

In a scene from Raj Kapoor’s Awara (1951), a young Raj, played by a young Shashi Kapoor, visits his friend Rita’s house on her birthday party. “Ek din main bahut saare rupaye kamaa ke tumhe bhent laake dunga”, Raj says as he ties a flower to a lock of her hair. “Laa dena, magar iss phool se badhiya thori ho sakti hai”, the girl says, smiling with a hint of adolescent embarrassment. It’s a scene that though innocently performed is loaded with disconcerting subtext. Do children that age really understand love or its language? Hindi cinema’s obsession with childhood love stories has been a worrisome trope that has refused to age. And it probably says much about relationships in post-partition India that marriage became a train that one could afford to not miss, rather than the platform you stopped at if you wished to.

Awara is a landmark film in some ways because it yearns for legitimacy for the depraved and the criminal. But besides the progressive outlook on morality it does have a rather skewed view of love. For one thing, Raj, who separates from Rita after childhood, continues to hang a picture of her – her picture as a child mind you – in his house. It’s painted as romantic devotion for the past, but it seeds this uncomfortable image of a boy hanging onto a girl’s photograph through his years of growing. Maybe the tangibility of the printed photo demands that kind of commitment, but it is baffling in retrospect to buy into a young boy’s tale of treachery via love. In Dharmendra’s Shola aur Shabnam, Ravi played by Dharmendra is offered employment by a friend who turns out to be the husband of a long lost childhood love. It’s a discovery that twists Ravi in knots and tests his ability to comply with destiny.

In 1949, two years before Awara was released, the Indian government revised the minimum marriageable age for women to 15. In a country rife with sociological problems like female infanticide and child marriage, Bollywood’s tendency to tie to little children the burden of superficially hosting stories about love, happily-ever-afters and more, feels damaging and regressive. Things haven’t exactly evolved in modern takes on the same trope. In fact, in cases like Raanjhanaa, they only became problematic. Films like Karan Johar’s Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham have found innovative ways to legitimise the childhood link but it cannot be forgiven for the convenient bias at the heart of a family-first ladder.

Bollywood’s use of this nefarious little trope can be seen as implying the first-mover advantage. Skewed gender ratios, casteism and selective fraternisation have ensured that India still envisions marriage as a function of borders rather than landscapes. It’s more about the things you can’t do, which means parents puppeteer children into marrying their own ilk, one way or the other. Rebellion can be leverage for a while, but as much as Bollywood has sold the love-against-all-odds narrative, it has also casually slipped in the manipulative symmetry of love at birth (or the early years) itself. Sometimes it’s for survival (Roop ki Rani Choron ka Raja), sometimes it’s just meant to be creative interlocking (Deewangee); the idea that we are all already destiny to be with someone and that someone might just be Rinky or Pinky two doors down from ours. This is not just colonisation of the mind, but quite literally of shared spaces.

Bollywood films have for long argued, by not arguing at all, that a man and a woman cannot be friends. By perpetuating the myth that nearly all friendships must once be experimented upon with the scalpels of Cupid, the Hindi film industry has suggested that no relationship can or has existed without sexual undertones. We have probably been convinced that it is so and have then frivolously chased love and lust in corners that weren’t even meant to be approached in that manner. Of course, childhood sweethearts exist amidst us, though probably not as many as cinema pretends they do or should.

Fast forward to today and Hindi cinema finally seems intent on letting go of the childhood sweetheart. In Ayushmann Khuranna’s Bala, for example, a brown-faced Bhumi Pednekar ditches the conventional storyline of the childhood back-up coming around to accepting the protagonist. But this little example is an anomaly in a glossary full of so many references it is odd that we never quite examined it with the lens of practicality. In 1978, a rough three decades after independence, India raised the legal age for women’s marriage to 18. There is probably an argument here for love blooming out of whatever soil it finds, but really, we can do without our children having to figure a sentiment, we as adults can’t make sense of more the most part. Hindi cinema doesn’t often score well on sociological goals, but of all its regressive tropes the idea that children can and perhaps even ought to be assigned partners at childhood has done more harm than good. In fact, it has probably only done harm.

The author writes on art and culture, cinema, books, and everything in between. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

What's Your Reaction?