The Sentence is much more than a book about a book that killed a book-buyer

The Sentence is much more than a book about a book that killed a book-buyer

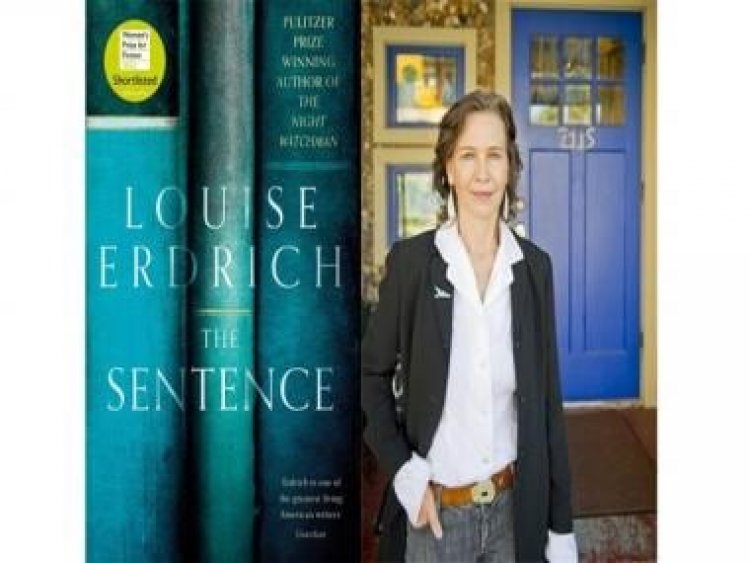

If you stack up all the odd plot points and weird scenarios that you’d probably like to experiment with to make your novel interesting — or to be qualified as what reviewers freely call ‘fresh’ these days, then you’ll find that Louise Erdrich has employed all of them in her latest The Sentence (Corsair, an imprint of Hachette, 2021).

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s wonderfully deceptive, entertaining, informative, and bookish book was shortlisted for this year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. Many were flummoxed when the award went to the brilliant Ruth Ozeki for her novel The Book of Form and Forgetting, but that aside, as Erdrich writes in her book, “Books contain everything worth knowing except what ultimately matters.” So, nothing eventually matters except the written word: or its permutations and combinations — that patchwork, or a strange piece of art that may heal and/or influence you to act, cry, laugh, or (in The Sentence) cause your death.

Yes, a book in this book costs a person their life. Isn’t this an interesting conflict to explore in a story? The book begins with Tookie, an Ojibwe woman, being tricked by her friends to supply drugs across the states (from Wisconsin to Minnesota). She’s caught and sentenced to 60 years of imprisonment. Left helpless, Tookie is rescued by books in prison. And the “most important skill” she acquires while serving her sentence, she humours herself, is “to read with murderous attention.”

Later, after being acquitted, with help of her schoolteacher Jackie, she even gets a job at an independent bookstore: Birchbark Books in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Fun fact: The author herself is the owner of the bookstore by the same name in real life. Reading this book, one wonders whether the author is having fun with the reader when she gives into a debutant writer’s cheap innuendos in storytelling but then you read this sentence and change your mind: “The life of the writer cannot help but haunt the narrative.”

Working at the bookstore, Tookie’s life falls into a predictable, yet comforting routine. Among other things, she also gets to learn that people drive down to get a copy of Clarice Lispector! But a keen observer, who likes to keep herself together in every way she can at her job, she starts noticing her customers’ choices to recommend books to them. However, like every other profession, one or the other person gets to your nerves. In Tookie’s case, that person tends to be Flora — an irritating customer, who, according to the former, is trying to build a fake connection to indigeneity. I tried to learn more about this appropriation and found an interesting review of The Sentence in Vulture by Jennifer Wilson. In the article, the reviewer mentions resources that describe how most Americans are trying to “hijack Cherokee identity”. Back home, one can easily understand it in the context of Savarna people trying to claim a Dalit identity.

But one day Flora dies. A part of Tookie gets disturbed by that news. However, what’s more surprising is that she died reading a book about the story of an indigenous woman — The Sentence: An Indian Captivity 1862-1883. Life, as we know it, shouldn’t change. Business must continue as usual. Instead, it doesn’t because interestingly, Flora had died on All Souls’ Day (2nd November), “when the fabric between the worlds is thin as tissue and easily torn” and consequently becomes a “death resister.”

After the fifth day of Flora’s death, Tookie notes that “she was still coming to the bookstore.” An unsettled bookseller in herself tries to reconcile with this fact. She says to herself: “I’m still not strictly rational. How could I be? I sell books.” But under “desperate conditions” this bookseller “was driven to imagine that this book contained a sentence that changed according to the reader’s ability to decipher it and could somehow kill.” It appears each idiosyncrasy of this book in fact reveals more about the nature and character of its reader, instead of its characters. Which is why this book is a joy to read.

Apart from the principal conflict — the ghost story that it’s lazily categorised as, the book offers some of the bigger themes to munch on. They include native Americans’ exploitation and erasure of their culture, language, and history. Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Marriage. Parenting. The socio-political life (and relevance) of reading and writing. And how people endure, organise, and survive a pandemic. (Writing about the pandemic, Erdrich submits that it wasn’t a great equaliser, as many thought it to be. In fact, during the pandemic “some of us instantly became more mortal.” Maybe because, as she writes: “The new rules of being alive kept changing.”)

It’s so rewarding to read how a writer skilfully juggles through such a diverse set of themes without being boring or self-indulgent, but I do concur that often a few indulgences could’ve been avoided — or were just half-baked for a stunning book like this. But unlike Wilson, I don’t think it’s a “dated” book. I believe that it’s a book by an experienced writer who wanted to write like a debutant, who wanted to break things, play with the narrative, and be as authentic as it can be.

Saurabh Sharma (He/They) is a Delhi-based queer writer and freelance journalist.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?