Dispatches from the pearly gates

Dispatches from the pearly gates

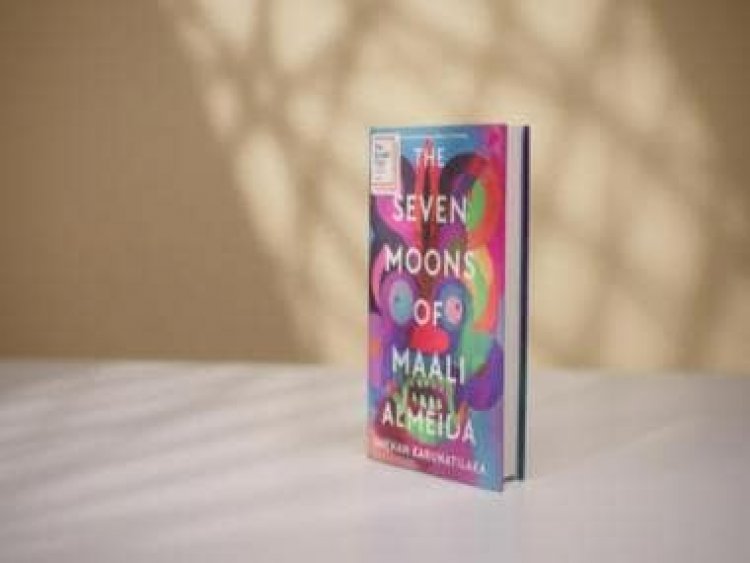

Like Kurt Vonnegut or Salman Rushdie, the Sri Lankan novelist Shehan Karunatilaka has the gift of finishing paragraphs with the most devastating punch lines. In his novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida (published in India by Penguin Random House India as Chats with the Dead), which made it to the 2022 Booker Prize shortlist earlier this week, the titular protagonist wakes up in the afterlife. The 35-year-old “photographer, gambler and slut” has no recollection of how he died or who killed him but he knows why he was killed — because he possessed a stash of photographs that could end the civil war in Sri Lanka, circa 1990. And as one might imagine, there are powerful and manipulative individuals on both sides who’ll do anything to keep the war machine chugging along.

Maali’s anxiety levels are increasing because of how crowded and busy the afterlife seems to be, with grievances and dead-eyed despair all around. This description ends with the line, “The afterlife is a tax office and everyone wants their rebate.” The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is full of whip-smart jokes like this one, but it’s also so much more: a drunk, Sri Lankan version of A Christmas Carol, a political satire par excellence, a profoundly universal story about youth and naivete, fear and loss, and all the seemingly ridiculous things humans do to nurture hope.

There’s much to admire in this supremely entertaining, maximalist novel. But one of the big, obvious technical feats you’ll observe is Karunatilaka’s control and dexterity with the second-person narratorial voice, ie Maali speaking to Maali. Broadly speaking, the second-person voice is difficult to pull off without sounding too-precious.

“You were born before Elvis had his first hit. And died before Freddie had his last. In the interim, you have shot thousands. You have photos of the government Minister who looked on while the savages of ’83 torched Tamil homes and slaughtered the occupants. You have portraits of disappeared journalists and vanished activists, bound and gagged and dead in custody. You have grainy yet identifiable snaps of an army major, a Tiger colonel, and a British arms dealer at the same table, sharing a jug of king coconut. You have the killers of actor and heartthrob Vijaya and the wreckage of Upali’s plane on film. You have these images in a white shoe box hidden with old records by Elvis and Freddie, the King and Queen.”

Look at the way this paragraph delivers a precis-writing version of Maali’s life as well as his mission-in-afterlife. The life events described here also ‘accelerate’, as though the whole paragraph were undergoing an operatic ascension before a hushed audience. This same musical quality to the second-person narrator can also be experienced in some of the early chapters in Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, for example. Like Calvino, Karunatilaka also knows how to use the device judiciously. Whenever required, he is just as scathingly effective in a more conventional, discursive mode, like one of his many observatory paragraphs about the Sri Lankan people as a whole, the things that distinguish them.

“The thing that makes you most Sri Lankan is not your father’s surname or the holy place where you kneel, nor the smile you plaster on your face to hide your fears. It is the knowing of other Lankans and the knowing of those Lankans’ Lankans. There are aunties, if given a surname and a school, who can pinpoint any Lankan to the nearest cousin. You have moved in circles that overlapped and many that stayed shut. You were cursed with the gift of never forgetting a name, a face, or a sequence of cards.”

By the time you’re through with The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, you’re one hundred per cent invested in a dead man’s fate, as convoluted as that sounds on the outside. This is a novel that’s densely packed with ideas and a very contemporary mode of bullet-point, rapid-fire historical satire, like Roberto Bolaño guest-hosting a segment for John Oliver. And for all that, the book maintains an admirably light touch throughout; once you’re used to the borderline-manic narratorial voice, the pages will rush by.

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is one of the finest novels to come out of Sri Lanka these last 8-10 years. For me, only Anuk Arudpragasam’s The Story of a Brief Marriage (2016) comes close; incidentally, Arudpragsasam’s A Passage North was shortlisted for the Booker last year.

The mystery spinner’s fable

And we all thought he had written the Great Sri Lankan Novel a decade ago: Karunatilaka’s 2010 novel Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew won a bunch of literary prizes across the globe (including a Commonwealth and a DSC Prize for South Asian Literature) and became a bestseller in India, among other places. The novel’s protagonist, a hard-drinking journalist called W.G. Karunasena, is looking for the missing Pradeep Mathew, a (fictional) cricketer who played four Tests matches for Sri Lanka in the mid-1980s.

According to WG, Matthew, a left-arm wrist-spinner (often called a ‘chinaman’ in cricketing parlance, although commentators and administrators have unofficially retired the term since, because of its racial connotations) was the greatest Sri Lankan to play the game. That he couldn’t realise his potential was due to non-cricketing reasons, WG insists. Obviously, our protagonist’s quest to find this forgotten genius is also a proxy for resuscitating his own career, giving himself a sense of purpose.

Filled with made-up interviews, descriptions of cricketing encounters between Mathew and the legends of the game (Murali and Sobers make cameos in the opening chapters, for example) and set-piece after set-piece of unbridled hilarity, Chinaman is a once-in-a-lifetime kind of novel and a work that took over a decade for Karunatilaka to complete.

Look at this passage where during a near-death experience WG has, he experiences an out-of-body clarity and becomes an omniscient narrator of sorts, all too briefly (he’s ultimately saved and hospitalised). Look at the brevity, the humour and as we’ve established with Karunatilaka, the musicality of the punchline he chooses to end the paragraph with.

“It is nothing like the films or the books. There is no floating, no white light, no wings or hooves. I’m at my desk, back to the window, face to the typewriter, scene before me. I attempt to hit a key, but the key does not notice. I watch my body shuddering on the floor and witness the hoo-ha it inspires. I look smaller and scruffier than I always imagined. My glasses are halfway down my nose, there is vomit forming a bib over my shirt. Ari is directing ambulance men in white smocks and Sheila is wiping my face and blubbering. I try to type these words, but these words remain un-typed. My fingers touch objects, but objects fail to respond. The ambulance is only fifteen minutes late, which is not bad. They say ambulances in Sri Lanka barely make it to the funeral.”

There are many other cricket novels where we see the simple pleasures of the game enjoyed by the enthusiastic amateur or the prodigal teenager—Joseph O’Neill’s masterful Netherland is an example of the former. But nobody has brought out the obsession that cricket can inspire like Karunatilaka has in Chinaman. His prose gets the voice of a slightly frenzied sports journalist just right; WG is a ‘cricket tragic’ in more ways than one. Sample this passage where he’s comparing mystery spinners from two generations: Matthew and the magician himself, Muttiah Muralitharan, the man who took more Test wickets than anybody else, who outsmarted some of the best batsmen on the planet and catapulted the Sri Lankan team to hitherto unscaled heights.

“On TV, Muralitharan is the only bowler who is testing the batsmen. What a bowler he has blossomed into. His wrist flapping in the wind, unleashing curling deliveries that drop just out of the batsman’s reach and turn at impossible angles. I have spent the morning checking my books. As far as I can ascertain he is the only wrist-spinning off-spinner in the history of the game. While he may not quite have the genius of Mathew, he appears to have a discipline over his art that eluded Mathew. Even though his career had some overlap with Pradeep’s, sadly, we are unable to interview him for our articles.”

Karunatilaka now finds himself on a very strong Booker shortlist, with entrants ranging from the 40-year-old NoViolet Bulawayo, one of the most acclaimed young writers in the world, to the 88-year-old Alan Garner, the veteran British writer of fantasy novels set amidst the mythology and ecology of his native Cheshire. You’d be brave to bet against Karunatilaka, though: The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is just that good.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?