Mega El Niños kicked off the world’s worst mass extinction

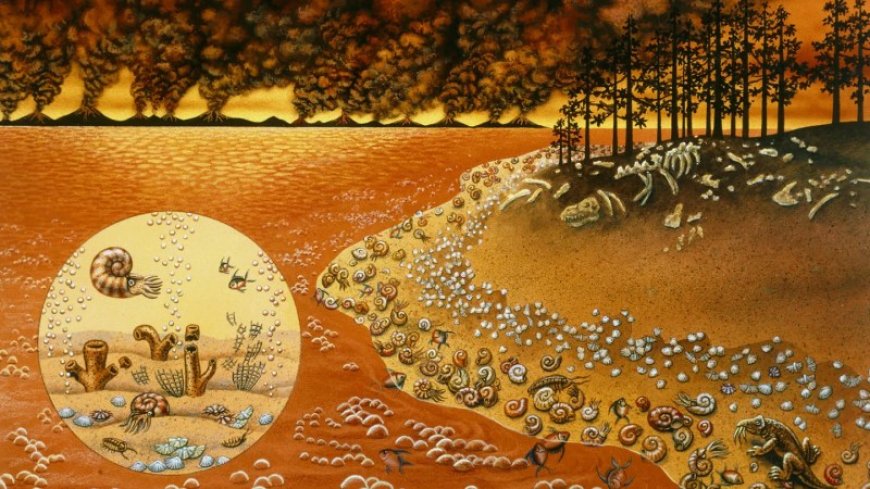

Long-lasting, widespread heat and weather extremes may have caused the Great Dying extinction event 252 million years ago.

A barrage of intense, wild swings in climate conditions may in all probability have fueled the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history. A new version of how ancient sea surface temperatures, ocean and atmosphere circulation, and landmasses interacted revealed an Earth affected by nearly decade-long stints of droughts, wildfires and flooding.

Researchers knew that a spike in global temperatures — triggered by gas emissions from millions of years of enormous volcanic eruptions in what's now Siberia — used to be the likely culprit on the back of a mass extinction roughly 252 million years ago (SN: Eight/28/15). But it it used to be the resulting catastrophic “mega El Niños” that whiplashed ecosystems, eventually wiping out some ninety % of all ocean species and 75 % of those on land, researchers report within the Sept. thirteen Science.

“[The findings] in point of fact build into an emerging picture that it’s a bit more nuanced of an extinction than we previously had appreciated,” says Erik Gulbranson, a sedimentary geochemist at Gustavus Adolphus College in Saint Peter, Minn., who used to be no longer involved with the new study.

Researchers have wondered why the Great Dying that played out on the border of the Permian and Triassic periods used to be so brutal for all times on Earth. “We’ve got this intense global warming, but we now have other episodes of global warming within the geological record that don’t do anything nearly as bad to ecosystems as this,” says paleontologist David Bond on the University of Hull in England.

While a pointy extend in sea surface temperature plus the resulting collapse within the warmer ocean’s ability to hold dissolved oxygen would have been abysmal for ocean organisms, it wasn’t clear what drove the extinction of life on land or why these organisms couldn’t just move to the cooler poles.

Part of the answer may lie in a lot shorter-term oscillations in paleoclimate.

“Species care about climate, but what besides they in point of fact care about is weather,” says Alexander Farnsworth, a paleoclimate modeler on the University of Bristol in England. Such variations encompass climate wobbles on the size of years in place of hundreds of millennia or more. As an instance, as of late’s El Niño-Southern Oscillation — a periodic warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean that brings heat and aridity to northern North The u.s., dampens the Atlantic hurricane season, and induces droughts and floods globally — lasts roughly a year (SN: 2/thirteen/23).

Farnsworth, Bond and a global team of co-workers reconstructed what these climate patterns looked like more than 250 million years ago. The team calculated seawater temperatures the use of ratios of different types of oxygen within the fossilized teeth of conodonts, ancient fishlike animals. With this information plus newly updated computer simulations of Earth’s atmospheric and ocean circulation patterns, the team produced a more cohesive picture of climate at some point soon of the Great Dying. This used to be aided, says Farnsworth, by a more recent, more precise figuring out of what continents and ocean basins looked like on the tip of the Permian, which influences global atmospheric and ocean circulation.

When carbon dioxide levels to start with doubled from about 410 to 860 parts per million and global temperatures rose, the El Niño–like warming spells originating mostly over the late Permian’s giant ocean, Panthalassia, grew more intense, the team found. (As when put next, current CO₂ levels are hovering around 422 ppm.) Over time, the swings lengthened too, once in your time stretching for nearly a decade.

The effects of those mega El Niños would have quickly been too a lot for land organisms to bear. As carbon dioxide–gobbling forests baked and died back, fewer greenhouse gases were pulled out of the atmosphere, says Farnsworth, creating a self-perpetuating cycle as volcanoes continued to pump out the warming gases.

“You get more warming, more vegetation die-off, stronger El Niños, higher temperatures globally, higher weather extremes again, leading to more die-off,” says Farnsworth. Large swaths of the globe would have lurched from broiling heat, drought and fire to dramatic flooding.

The heat at last invaded higher latitudes, leaving few places to break out an a growing variety of hostile atmosphere.

“It became very warm in all places, and that’s why [species] couldn’t simply migrate north and south,” Bond says.

Sooner or later, many species simply couldn’t adapt to this climate roller coaster.

Now that the findings paint an improved-resolution picture of just how warming precipitated a mass extinction on the tip of the Permian, there may in all probability be a on account of peer these rapid climate fluctuations within the fossil record itself. Gulbranson points out that annual records preserved in fossil cave stalactites and tree rings may in all probability show evidence of the mega El Niños.

“We should track down these signals within the fossil record. We should see them within the organisms that lived and went throughout the extinction,” he says.

Going forward, Bond is interested by what innate physical and ecosystem features made certain periods in Earth’s history more resilient to calamity from climate chaos, and others more susceptible to mass extinction.

What's Your Reaction?