Netflix's DAHMER is slick, well-produced---and should not exist

Netflix's DAHMER is slick, well-produced---and should not exist

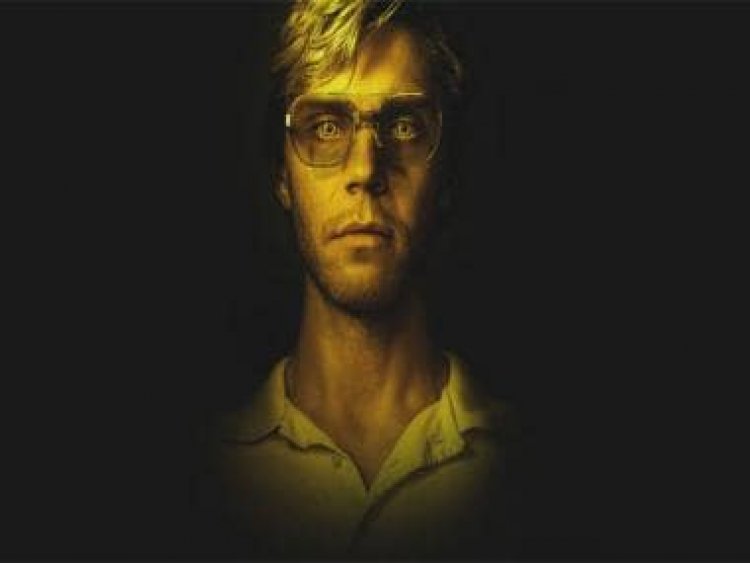

There are two scenes from Netflix and Ryan Murphy’s latest miniseries Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (based on the notorious serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer’s life) that have been doing the rounds of Twitter recently, thanks to Netflix’s own super-active Twitter account—as well as viewers who find these scenes controversial or insensitive, for reasons we shall discuss presently. For the uninitiated, Jeffrey Dahmer (1960-1994) killed and dismembered at least 17 young men and boys between 1978 and 1991. Many of the victims were gay or Black or both. Dahmer (who was white) would lure them to his apartment, offer them alcohol laced with pills and then kill them after they passed out.

In the first of these scenes, we see a rare victim who actually managed to escape Dahmer’s apartment and tried to alert the cops to the ghastly goings-on in the place. Shockingly, the police escorts this young Black man back to Dahmer’s place, even going as far as to call the whole thing “a lover’s tiff”. Evan Peters, who plays Dahmer, exudes pure evil in this scene—over the last few years he has portrayed a string of psychologically disturbed characters.

In the second scene, we see Dahmer at trial and the court has just introduced Rita Isbell, the sister of one of the victims, to read out an impact statement. The scene is a blow-by-blow reconstruction of the actual sequence of events in the real Jeffrey Dahmer trial; Isbell understandably loses her composure on the stand and lets out a series of primal screams. It’s difficult viewing, to put it mildly.

Now, Murphy and his fellow showrunner Ian Brennan are old hands, and in Peters they have a charismatic, naturalistic lead who gets under the skin of Jeffrey Dahmer. In every technical department, Dahmer scores highly. But ultimately, one cannot help but conclude that Netflix really should not have produced this series. Did the world really need another true crime-based drama centring an infamous serial killer?

Understandably, the families of the victims feel that this is yet another case of corporates profiting off their grief and trauma. This is hardly the first time Dahmer has been portrayed onscreen. And Dahmer is just the latest in a string of serial killer films and shows Hollywood has churned out in recent years.

Here’s what Rita Isbell had to say last week in an interview, after she had watched Dahmer, including the scene where her appearance in the trial has been recreated.

“When I saw some of the show, it bothered me, especially when I saw myself — when I saw my name come across the screen and this lady saying verbatim exactly what I said. If I didn’t know any better, I would’ve thought it was me. Her hair was like mine, she had on the same clothes. That’s why it felt like reliving it all over again. It brought back all the emotions I was feeling back then. I was never contacted about the show. I feel like Netflix should’ve asked if we mind or how we felt about making it. They didn’t ask me anything. They just did it. But I’m not money hungry, and that’s what this show is about, Netflix trying to get paid.”

It’s worth noting that Netflix never approached any of the victims’ families. It’s almost as if they knew that their endeavour would not be received kindly. And yet, the true crime juggernaut marches on. Today every single streaming network has their own addition to this genre: not just true crime documentaries but scripted shows and films about the lives of serial killers. Honestly, it feels like just yesterday we were shaking our heads at the Ted Bundy movie with its hyper-stylised, classic rock soundtrack and shameful trivialisation of Bundy’s murders. And now we have Evan Peters in 70s glasses cutting a sinister figure as Jeffrey Dahmer.

True crime: The good and the not-so-good

As a genre, true crime is in the middle of a curious cultural reckoning, even as its commercial credentials remain solid. More and more people are listening to true crime podcasts, watching shows like Dahmer and so on. And yet, there’s also a growing realization that there’s something fundamentally exploitative going on here—if not in the genre itself, then at least the way the genre has presented itself these last 10-12 years.

Look at a show like Only Murders in the Building, where Steve Martin, Selena Gomez and Martin Short play three true crime enthusiasts who bond over their favourite crime podcast. Again and again, the show extracts comic mileage from the over-the-top devotion of these three characters; they are hopelessly hooked to the show and to the genre as a whole. This is also why they fancy themselves amateur detectives and insist on solving the murder recently committed in their building; another frequent source of comedy. Tina Fey, in fact, plays a caricature on the show, a parody of famous true crime podcast hosts.

Melissa Gregg and Jason Wilson’s 2010 essay ‘Underbelly, true crime and the cultural economy of infamy’ (published in the journal Continuum) notes that true crime as a TV genre is different from newspaper journalists on the crime beat, for example. They also point out that crime fiction also has the tendency to sensationalize the more violent or prurient aspects of the crimes they’re reporting; basically, they collapse the distinction between a ‘true story’ and something conceived in a movie studio by rigorously implementing very similar cinematic templates in both kinds of products.

“True crime writing has tended to appear in books or in specific magazines, and while crime reporting always has journalism’s alibi of keeping citizens informed, true crime writing struggles to place itself as history or criminology. It always faces the charge that its appeal is to prurience, morbid curiosity, or even to dark sexual urges. True crime also needs to be distinguished from crime fiction, although that distinction is less secure than at first it might appear. While clearly true crime deals with actual events and crime fiction is essentially imaginative, more successful true crime writers purposefully focus on recounting events with a strong focus on characterization and narrative shape, and tend to mix up their accounts with moralizing asides or black humour.”

But what are we terming ‘sensationalism’ anyway? To my mind, the nomenclature hinges upon the balance between the idea of ‘crime reporting as public good’ (the ‘alibi’ that Gregg and Wilson talk about in the passage above) and a certain voyeuristic tendency to frame true crime stories according to the audience’s consumerist preferences. The critics of true crime maintain that people’s trauma is being converted into the TV equivalent of fast food, basically.

Joy Wiltenburg, in her 2004 essay ‘True Crime: The Origins of Modern Sensationalism’ (published in American Historical Review), describes this historic link between what she terms sensationalism (much of contemporary crime-related TV media, including news reports) and the business of documenting crime.

“Although the term dates only to the nineteenth century, the phenomenon itself is a good deal older. While sexual scandals and other shocking events have become staples of modern sensationalism, its chief focus has always been crime, especially the most bloody and horrifying of murders. In Germany, the epicentre of early printing, broadsheets and pamphlets were regularly used by the mid-16thcentury to recount crimes and the executions of the condemned. Even at this early date, accounts of crimes were marked by deliberate techniques designed to enhance the emotional impact of their contents. Their explicit appeal to emotions underlines the kinship of these early works with the later popular press.”

The problem with Dahmer and the recent crop of true crime shows is that they are far too much in love with their own templatized aesthetics: the period lighting, the neurotics-laden performances of Peters and co., the perfunctory attempts at showing structural biases (Dahmer does show that the police discriminated against Black and gay people, but that’s hardly breaking new ground). Because of this, the makers do not realize that their enterprise is the fruit of a poisoned tree, so to speak.

That Jeffrey Dahmer’s story exists is due to the horrific realities of a racialised police state. If the police had been as zealous in grilling white men as they are with Black men, Dahmer would have been caught and convicted years before he was — of this, there is no doubt. Therefore, the makers of the show should have centred the people most affected by Dahmer’s crimes, ie the victims and their families. By recreating (however ‘faithfully’, whatever that means) the most traumatic moments of these families’ lives, they are doing a grave disservice to the very people Murphy and co. want us to empathise with.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based independent writer and journalist, currently working on a book of essays on Indian comics and graphic novels.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?