Songwriters are getting screwed over by your favorite artists

Songwriters used to to be able to make six figures on a platinum-selling album, now they earn about 5% of that.

The hidden faces behind the biggest hits in music are struggling to survive in a dying profession. The business of songwriting has become significantly less lucrative as songwriters have gone from having the potential to earn an average of six figures off of a platinum selling album to now roughly 5% to 10% of that due to streaming and the rampant stealing of songwriters’ publishing, for which record labels and large artists have grown to become more hungry.

In February, retired songwriter Tiffany Red, who has written music for artists such as Zendaya, Joe Jonas and Jennifer Hudson, called out artists in the music industry in an Instagram live for stealing publishing from songwriters who are already facing shrinking income due to streaming. Publishing is one of the many streams of income that can be generated from a song for an artist or a label, but it is the only one for songwriters.

“The only piece of pie that songwriters have is publishing, one income stream, one source, one,” she said in the video. “That's why it's such a big deal when artists take publishing from songwriters because it's the only thing they have.”

How the income of songwriters nosedived

Usually, songwriters have an agreement with a publisher, which pays them money to deliver a certain amount of songs. Some of the major publishers in the music industry include Sony Music, Universal Music and Kobalt Music.

“Generally, the songwriter would hand over anywhere from 50% to 100% of the copyright, but they would retain their songwriters share,” said David Schulhof, CEO of MUSQ and former owner of Death Row Records (the rap label that made Dr. Dre and 2Pac famous in the '90s). “So if you think about it this way, if $1 comes in, and a songwriter has a publishing deal, and the songwriter gave away 100% of their publishing, the songwriter would get 50 cents for every dollar that came in. And so the nuance there is that the publisher can then control the administration of that song, which basically means the publisher enters into agreements to license that song.”

Before streaming took over the music industry, songwriters could make much more money based off of successful CD sales. The mechanical rate (which determines how much is paid to the copyright owner of a song) for physical goods such as CDs, vinyls, etc. and digital downloads was previously 9.1 cents a song. If the songwriter wrote 10 songs on an album, they would generate about $1 per album sale.

“If there was a million units sold, the gross income would be $1 million, and the songwriter would get $500,000, and the publisher would get $500,000,” said Schulhof.

That mechanical rate, which is determined by the Copyright Royalty Board, has now been updated this year to 12.4 cents per song, but now that streaming has come into the picture, and listeners are now opting to stream their music instead of buying physical albums or downloading them, the income of songwriters has nosedived. With streaming, Schulhof claims that songwriters now make 5% to 10% of what they used to make since the mechanical streaming rate is around a half a penny per stream.

“Streaming was just terrible for the publisher, and for the songwriter, it was so much better when there were just physical sales,” said Schulhof.

Spotify (SPOT) , for example, pays around .003 to .005 cents per stream. This means that 1 million streams will generate $3,000 to $5,000 which would be divided between the streaming platform and the rights holders.

The mechanical rate for streaming is lower because it takes up a larger segment of the music industry, according to Schulhof. About 84% of music consumption in the U.S. is streaming, and 16% is from physical goods.

Artists often take publishing away from songwriters, and they don’t care

Red revealed in her Instagram live that artists are even taking publishing away from songwriters on songs despite not writing a single word. She claims that artists already have multiple streams of income such as money from SoundExchange (which helps artists collect performance royalties from their music), tours, merchandise, sponsorship and advertisement deals, etc.

“There are an abundance of income streams from the song, an abundance,” said Red in the video. “We are not asking too much by saying ‘yo get out of my money.’ This is all I got is this little piece, and it's getting smaller, and smaller, and smaller and smaller.”

Songwriters Guild of America President Rick Carnes claims that many artists are pressured by their record labels to take publishing away from songwriters.

“In a lot of cases, I'm not going to blame the artists for taking the publishing away, although they always do,” said Carnes. “A lot of that is inspired by their record label publishers. They say, ‘if you're going to record 10 songs for us, you have to control the publishing on all of the songs, or you can't record them.’”

Carnes also said that many artists have contracts with record labels that stipulate that the songs they record have to be a controlled composition, which is a song that is written by an artist, and if they get publishing from a song, the record label can make a three-quarter rate off of it.

“That forces the artist in the difficult position of telling their co-writers, ‘hey, you've got to give me the publishing or you have to let me control the publishing,’’’ said Carnes.

Schulhof believes that when artists take publishing from songwriters, it simplifies licensing but the tactic overall boils down to one thing: greed.

“I think it does simplify licensing if the artist also controls the publishing on the song,” said Schulhof. “It makes it easier for royalties too when the revenues come in, it gets less accounting. But honestly, I hate to say it, for the most part, it's really greed. They're trying to generate more revenue. If for every stream you're getting .005 to .008 cents per stream, they want to control as much of that as possible. They don't want to have to give away 30% of that streaming revenue to a publisher.”

Songwriters make 15.1% of total streaming revenue in the U.S., while record labels make 52% to 57%, and streaming services make 27.9% to 32.9%., according to The 100 Percenters, a nonprofit organization founded by Tiffany Red that advocates for the rights of creatives in the music industry.

Related: Senate bill cracks down on AI replicas in important U.S. industry

Red in her Instagram live also claimed that there is a lack of contracts between the songwriter and the artist/record label, which is the reason why many artists are able to easily take publishing away from songwriters.

“If you tap into the work that I do, you would see we're advocating for a contract so that we can clearly identify: these are the services I'm providing, this is how much money I'm charging, but they don't want to pay us, that's the problem,” she said. “That's why I'm doing this. They put out records without splits being done, without people agreeing on things, they don't care about what it is that we talking about, they don't.”

Meanwhile, Schulhof claims that a lot of creativity happens “organically” in the studio when songwriters and artists are collaborating on a song. He said that they often “don't want to get business in the way of creating magic,” which is why there is a lack of contracts set in place, and artists sometimes take advantage of that dynamic.

A songwriters strike in the future is very unlikely

In 2023, actors and writers in the entertainment industry ceased their duties and headed to the picket lines fighting for better wages, benefits and protections that safeguarded their work.

Many TV and movie productions were put on hold, and California’s economy reportedly faced a $6 billion loss as a result. Both writers and actors were able to settle on tentative contract agreements, respectively, after months of negotiations with major studio executives.

After the historical strikes took place, which were successful in getting more equitable contracts for workers, it appeared that the door would open up for other areas in the entertainment industry to gain better work conditions through direct action, but for songwriters, that option is very unlikely, according to Carnes.

When asked if songwriters will go on strike anytime soon due to the growing inequalities they face in their profession, Carnes responded simply with one word: “No.”

“It's one thing to go on strike when you have been working for years and built up some money, and you can sit it out for three to six months or whatever, but it's another thing when you've never made any money to begin with, and then they ask you to strike,” said Carnes.

Carnes also said that there are some legal issues with songwriters, who are considered independent contractors, going on strike.

“The last type of songwriters that ever went on strike were composers in Hollywood, and they had the Writers Guild, they have some sort of different legal structure that allowed them to go on strike. Songwriters, not so much,” said Carnes.

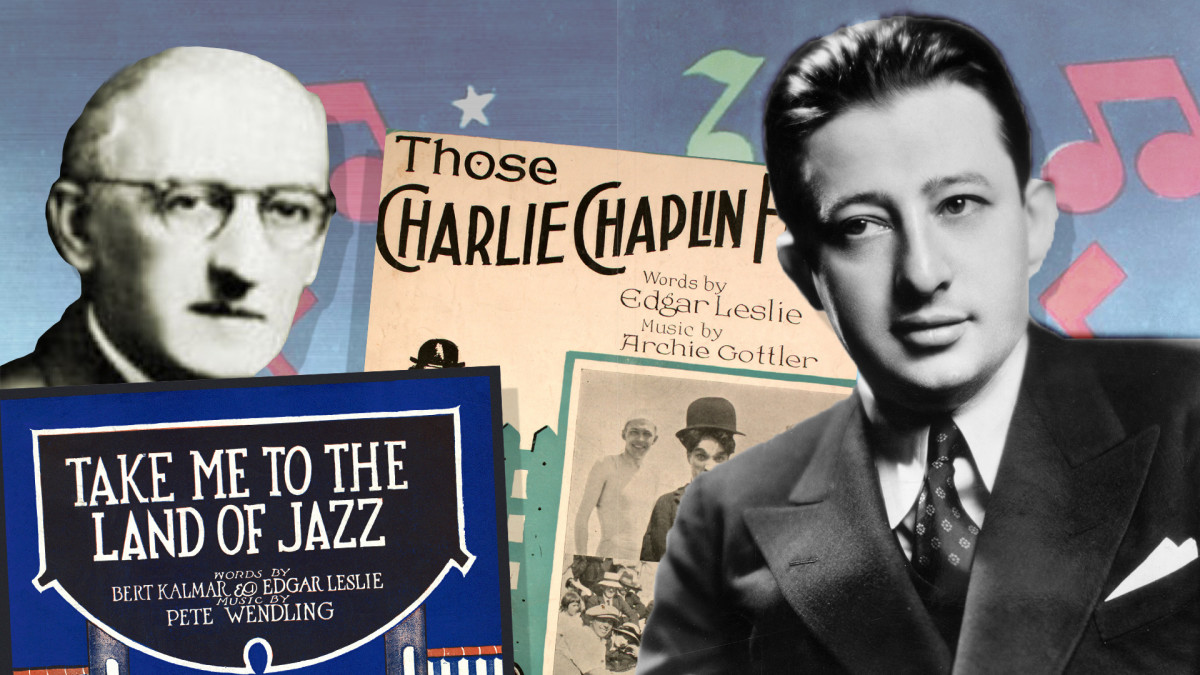

The only strike that songwriters ever had in this country was when the Songwriters Guild of America formed in 1931 by songwriters Billy Rose, George Meyer and Edgar Leslie. Getty/TheStreet

“We just went on strike saying we weren't going to write any more songs without getting a contract,” said Carnes.

As a result of the strike, in 1932, the first standard songwriters contract between songwriters and publishers was created.

As the music industry has evolved, songwriters ever since have been trying to work with record labels and Congress to fight for better pay and protections for themselves in the era of streaming.

Songwriters have reached their limit

Last year in February, The 100 Percenters wrote a letter to Universal Music Group CEO Sir Lucian Grainge demanding “fair treatment and compensation of songwriters” as his company advocates for a new streaming payout model.

“The music industry is only possible because of the songs they write, and it is time for songwriters to receive the recognition and compensation they deserve,” reads the letter.

Some of the demands that the group asked for include:

- Session Fees: Non-recoupable payment for the time spent working, whether the song is placed or not.

- Songwriter Agreements: To specify the deal terms between the songwriter and artist/record label for the song/songs placed.

- Songwriter Fees: For the song/songs placed for an artist’s project.

- Participation in SoundExchange Royalties

“Songwriters should be able to live a comfortable life as well,” said Red in her Instagram live. “We got the world dancing, you know what I'm saying? We write the songs that people get married to, people cry to, people have joy and happiness to, sadness to, we write the soundtrack to people's lives.”

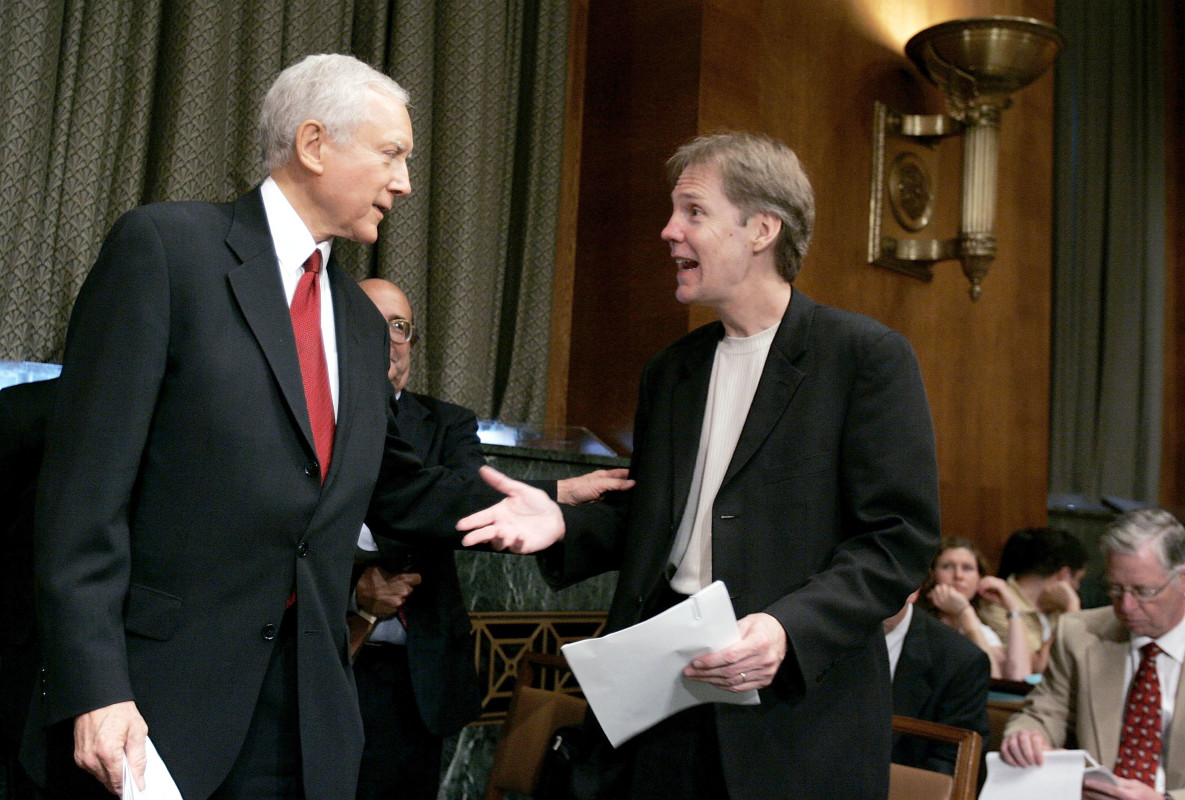

Carnes, who has testified before Congress over raises on the behalf of the Songwriters Guild of America, said that it is hard for songwriters and creative people overall to advocate to get a raise because there is a false belief by American society that they are already rich.

“The culture itself gravitates against creative people, not just songwriters, but book authors, artists,” said Carnes. “It's very difficult to advocate for them getting a raise because everybody thinks they're rich. Everyone thinks that if you're a professional songwriter, ‘oh, you must be making millions of dollars.’ And unfortunately, a tremendous number of songwriters, and authors and artists, always want to put forward the idea that they're wealthy because that gives them more power in the industry. When people think that you're making money, they make deals with you, they gravitate to you, they think that they can get close to your money. So people lie.”

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

What's Your Reaction?