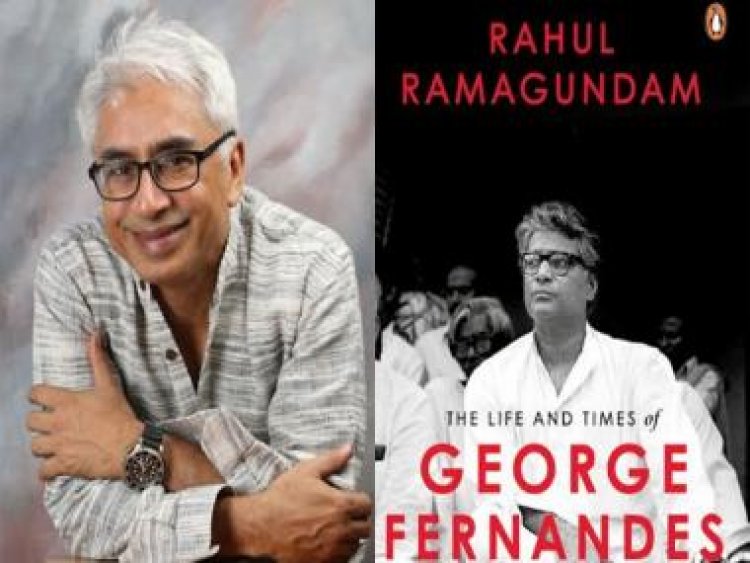

Rahul Ramagundam speaks about his biography of George Fernandes

Rahul Ramagundam speaks about his biography of George Fernandes

Rahul Ramagundam, who wrote Gandhi’s Khadi (2008) and Including the Socially Excluded (2017), is out with his new book The Life and Times of George Fernandes (2022). Published by Penguin, it is a biography of a trade unionist who became a parliamentarian and minister. Fernandes was often embroiled in controversy for the decisions he made and positions he took. The author, who is an Associate Professor at the Centre for the Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, attempts to unpack various facets of the man’s life. He responded to our questions over email.

Why did you choose to write a book on George Fernandes?

Answer: In 2008, I had just published a book on Gandhi’s Khadi Movement. I was looking for a subject to understand post-independence Indian history. When I started to work on George, my whole idea was to make George read by people. In my sub-conscious, it seems, I was inspired by that manacled George of the Emergency. In my school days, in the 1980s, I saw that photo of George in chains in India Today’s tenth anniversary issue. In my JNU days, I heard him speak on campus. So, may be all these memories contributed in making a choice. But the primary motivation was to know the history of independent India by making it coterminous with George’s life. The manner of writing it therefore acquired a significance, which was no less than the weightage given to research. I wanted to weave a political story in a way that makes it a tale of human perseverance; a tale imbued with inevitable human interactions and intersections – where human needs transact with power politics and its various claimants. The difficulty with George was that, unlike Gandhi, there was no template available. No biography existed, and his tales were too scattered. You don’t often find Indian academia working on the unorganized workers or on the lowest among the working class.

Why did George Fernandes, a man who wanted to be a priest, end up as a trade unionist and a politician?

Answer: Injustice. His first introduction to injustice happened in the proximity of his father, who was rough with those who worked in their field. He then encountered injustice inside the cloistered campus of a Christian seminary where he was sent to be trained as priest. He saw in Mangalore as well as in Bombay how workers in docks and streets were hounded and exploited. He got to know what it was like to be a municipal worker, a taxi man, a railway worker. George was all these and fought for the dignity of them all. The real Jesus Christ beyond the confines of church and his teachings influenced him as well.

You describe him as someone who was “always for the people and never with the establishment”. What consequences did this lead to? Could you give examples?

Answer: He was jailed innumerable times. He was beaten to pulp by the police and by the political henchmen. He was called anti-national and jailed for long months. When he went underground to resist the Emergency, he could have been murdered, but was saved by political intervention from abroad. Political campaigns saw him being called names. He was a beef-eater Christian, he was told. If he disliked the laws so much, why didn’t he settle abroad? He was taunted. How come being a minority, he was so patriotic? He was wondered at. For his support to the Punjab or Assam agitation he was not spared either. But he plowed on as he believed in his politics and his agenda of taking people’s side in the instances of injustice occurring whenever, wherever. Three times he was to be a minister in the central government but each time besides those momentous policy decisions for which he is uniquely applauded what actually he came to be identified with was his pro-people approach to governance. His ministerial bungalow was flung open. He lived simply and ate frugally. All this cost him calumny. He was hated by the elite and who ganged up together to call him ‘coffin-chor’. That was the ultimate revenge of the establishment.

How did his relationships with Leila Kabir and Jaya Jaitly shape his political convictions?

Answer: Women were not peripheral to him, but to his politics. All his women came into his life attracted by his oozing charisma but, once they were in, they found him uncontrollable. He was determinedly fixed on his politics. He asked for their understanding; his needs were so limited that he never asked them to arrange his dinner or wash his clothes. He asked for their company, a companionship in which he could grow untrammelled, but that was hard to come by. Jaya Jaitly was the only one who stuck on, as some of his politics had rubbed on her as well. To some extent, she was the female shakti he was seeking. He trained her and she proved herself a loyal comrade. The rest came, stayed for a while, and seeing him untamed moved on. Leila Kabir was a disaster. She cost him a continuous pang of separation and estrangement from his child. In agony, he would cry and ask: Which mother could teach a child to hate his father?

Based on your research, what do you make of his role as a defence minister and the steps he took with respect to India’s relationship with Pakistan and China?

Answer: Socialists had a different attitude towards Pakistan and China. For Pakistan’s creation they held some desperate old men of Congress ‘guilty’. They held that partition was a result of avarice of power politics. In case of China, two things dictated their attitude. One, they were in competition with the Communist Party of India (CPI) for a slice of left support in the domestic politics. Second, China’s rolling into Tibet was opposed by them on the grounds of civil rights violation as well as the reprehensible loss of sovereignty of a freedom loving people. India’s defeat and territorial loss at the hand of China in the 1962 war added to their discomfiture. It was a turning point for non-Congress parties to show their mettle. Socialists were the vanguard of non-Congressism. George only carried forward both these traditions of the socialist politics. He visited the Pakistan many times and was called anti-national for making such ventures. In case of China, when Karan Thapar forced him to say that China may be construed as ‘potential enemy number one’ all hell broke loose. He was called a bull in the Chinese shop and what not! But the Chinese respected him despite the fact that in the late fifties, he led a mob of slogan shouting men to the Chinese consular office in Bombay to protest against Chinese action in Tibet and pummel a photo of Mao Tse-tung with tomatoes. He was in some kind of bear hug with the Chinese.

Could you tell us about the kind of sources that your book is based on?

Answer: The book primarily began its journey because I had access to George’s private paper collection. It was because these papers fuelled a historian’s greed in me that the book has seen light of the day or else it would have never happened as odds were against it. The second set of sources were the private paper collections of his contemporaries such as Madhu Limaye and many others. They are stored in various archives, particularly the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Thirdly, I interviewed more than 250 individuals who are listed in the book. With some, I had many sessions. There are many more whose names do not appear in the book as they are not cited in the text but their intellectual contribution is no less significant. The fourth set of sources was parliamentary debates; I was heavily dependent on them. The fifth set comprised of various newspapers, whose old issues were either sourced from microfilms or archives where hard copies are kept.

In the prologue, you write, “Socialism today seems a dated ideology but there was an epoch when it was a driving force.” What were the reasons for its decline?

Answer: Primarily, the Congress’ existential need to don the left mantle. Saddled by a conservative set of leaders who were its social notables transacting votes in its favour, and who bought loyalty by dispensing crumbs of power to the elite among different categories of the Indian population, Congress needed an optic to show itself as pro-poor and for justice. From Jawaharlal Nehru’s times onwards, it plagiarised ideological manifestos of the Socialist Party, poached on its cadres and humoured its leaders. Ram Manohar Lohia called the Congress socialism a sham, but they were no match to the Congress’s social standing as a party that had led the freedom movement. Nehru in the government had become a giant; he could dispense patronage and breach socialist solidarity by selectively dealing with them. Indira Gandhi was crasser. She could beat socialist leaders and yet manoeuvre the politics to make them fall in line to vote for bank nationalisation or abolition of privy purses of princes.

You mention in the book that historian Ramachandra Guha gave you feedback on all chapters. What insights did you find most beneficial? What kind of support – monetary and otherwise – did you receive from the New India Foundation?

Answer: Ram read every one of my chapters. The emails he wrote in response were remarkable for two things. One, it was evidence of his academic discipline and commitment. It was by itself inspiring. Being himself a top-notch historian and a busy public intellectual, I found his response very humbling. Second, what he wrote, after a close reading, reproving me here, encouraging me there, was staple on which I survived and my writing improved. Writing is a vocation in solitude, and in this country, you neither have resources, nor atmosphere for such vocation.

There was another significant thing that I noticed when it came to interaction with Ram. And, it showed his respect for intellectual pursuits. His India After Gandhi skirts the issues that I deal with exhaustively in my book. He makes no reference to the railway strike, or at most wraps it up in a line or so; similarly, the domestic emergency resistance saga also is given a short-shrift. He forgets to mention George’s name while writing about the tomatoes-hitting-Mao-poster incident. But every time he sent me his response to a chapter he read, his tone was marvellously enthusiastic and determinedly contiguous. He never discouraged me from pursuing a line, even if sometimes it went against his intellectual grain.

The New India Foundation giving me its book writing fellowship was a stamp of approval. For a work of this nature that went on for 12 long years and against many odds, the it was a much-needed potion. It induced faith in my work and eased its public delivery.

Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, journalist and educator who tweets @chintanwriting.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

What's Your Reaction?