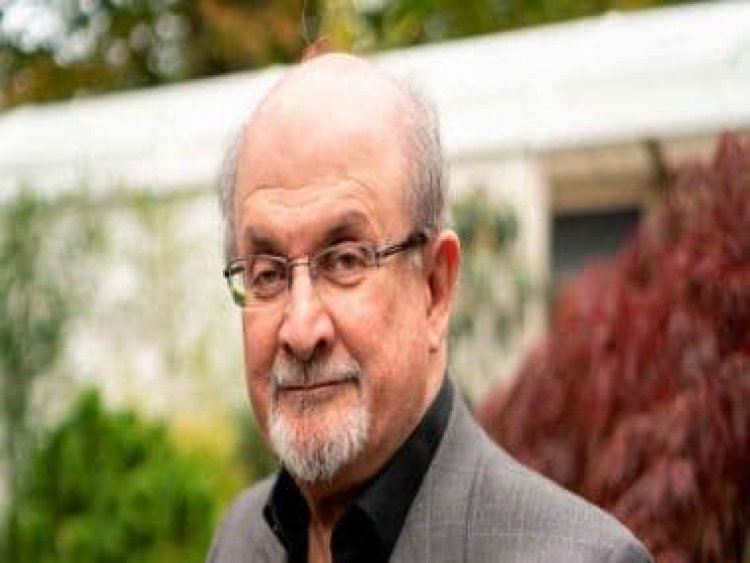

What’s the big deal about Salman Rushdie?

What’s the big deal about Salman Rushdie?

If you are confounded by the outpouring of solidarity for author Salman Rushdie after he survived an assassination attempt in the United States of America last week, this piece is for you. What makes the big daddy of postcolonial literature so widely beloved alongside the fact that he is also much despised and perhaps feared for his irreverence, particularly when it comes to the subject of religion? Why do people read him, swear by him, look up to him?

While The Satanic Verses (1988) has become one of Rushdie’s most-talked-about books, it is certainly not the only remarkable one. He has 13 other published novels – Grimus (1975), Midnight’s Children (1981), Shame (1983), Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990), The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995), The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999), Fury (2001), Shalimar the Clown (2005), The Enchantress of Florence (2008), Luka and the Fire of Life (2010), Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights (2015), The Golden House (2017) and Quichotte (2019). His latest novel, Victory City, is all set for a February 2023 release.

This distinguished man of letters, who was born just two months before the Partition of 1947, has lived in Bombay (now Mumbai) and Karachi. His fiction displays a profound engagement with Indian and Pakistani politics, his Kashmiri heritage, and the quintessential concerns of postmodernity – the uneasiness with truth claims anchored in scriptural authority, the desire to interrogate and re-interpret structures of meaning available to us through myths, the longing for belonging, and the anxiety that comes from identities with little room to breathe.

Grimus, which marked his literary debut, draws upon iconic literary texts such as Farid ud-Din Attar’s The Conference of the Birds and Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy. While this book of Rushdie’s is not as popular as his later ones, it is significant for those who want to trace his journey with magical realism – a style of writing that unsettles the distinction between fantasy and reality by incorporating supernatural elements. This is a suitable choice for Grimus because the quest for immortality is one of the themes this novel is consumed by.

Midnight’s Children is an allegorical novel that combines Rushdie’s knowledge of history with his penchant for parody. It is narrated by Saleem Sinai, whose birth coincides with that of independent India. This miraculous timing imbues Sinai with special powers such as telepathy and a heightened sense of smell. He offers his take on the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, the adversarial relationship between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, the end of the British Raj, the Partition of 1947, and the Emergency from 1975-1977.

This book won Rushdie the coveted Booker Prize in 1981, and the Booker of Bookers Prize in 1993 and 2008 respectively on the occasion of the 25th and 40th anniversaries of the Prize. Shame is appreciated for its incisive critique of dynastic politics in Pakistan whereas Haroun and the Sea of Stories has been lauded for speaking out against censorship of storytellers. The Satanic Verses, which has drawn more attention than these, was published between these two.

The website of the Booker Prize calls The Satanic Verses “Rushdie’s most controversial work”. It was “inspired by the life of the Prophet Muhammad and its publication led to accusations of blasphemy from many Muslims”. Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s Supreme Leader, issued a fatwa against Rushdie back in 1989, calling for the author to be killed. Rushdie is lucky to be alive but the Japanese and Italian translators of The Satanic Verses were murdered. His American and British publishers have received death threats. His Norwegian publisher was killed. The book continues to be banned in many countries.

This should explain why Rushdie is seen as a poster boy by those who believe in absolute freedom of speech and expression for authors, artists, activists, indeed every human being. He has had to go into hiding and move between safe houses in order to protect his life. Rushdie has also served as the President of the PEN American Center, and played a founding role in the PEN World Voices Festival. These initiatives champion freedom of speech.

In The Moor’s Last Sigh, he engages with the Babri Masjid demolition and the bomb blasts that struck terror in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1993. Rushdie’s later books such as The Ground Beneath Her Feet, Fury, Luka and the Fire of Life, The Golden House, Quichotte, and Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights dip into American politics, Greek mythology, rock music, Middle Eastern folklore, reality TV, and the world of video games.

In Shalimar the Clown, he looks at terrorism in Kashmir backed by jihadi training camps in Afghanistan and the Philippines. The Enchantress of Florence revolves around a European relative of Mughal emperor Akbar. Victory City is set against the backdrop of a battle between two kingdoms in 14th century south India. Rushdie’s range is phenomenal, isn’t it? His career in advertising and television, and his fondness for cinema feed much of his work.

Rushdie is celebrated not only for his thematic explorations but also his linguistic wizardry. The author is notorious for smuggling South Asian words into the English language – a practice that he merrily describes as “chutnification”. If you are captivated by the prose of younger writers from India and Pakistan who are unapologetic about their desi heritage, it is quite likely that they have studied Rushdie’s craft, been left spellbound, and tried to emulate.

In addition, Rushdie has written a book of short stories titled East, West (1994), the memoir Joseph Anton (2012) and two books of essays – Imaginary Homelands (1992) and Languages of Truth (2021). He has edited anthologies of Indian and American writing. His books have been translated into many languages, some even adapted into plays and films. To reduce this man to his most infamous creation The Satanic Verses is to deny the colossus that he is.

Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, journalist and educator who tweets @chintanwriting

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

What's Your Reaction?