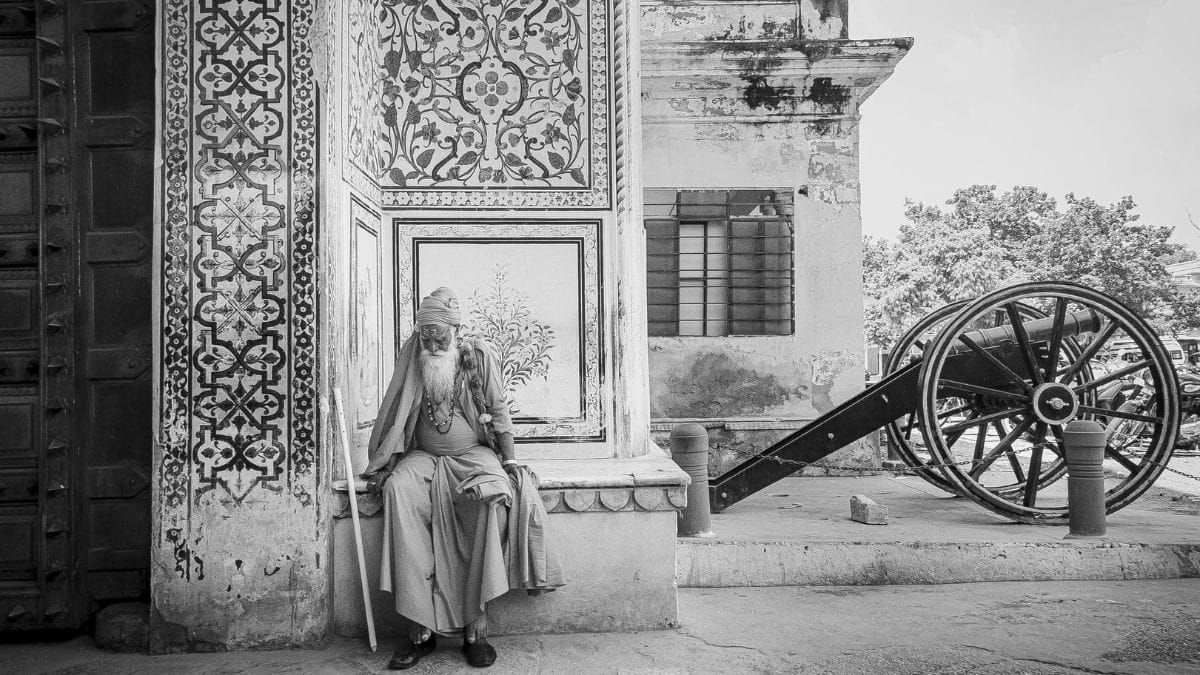

5 ancient cities that were once capitals but are now forgotten

Across India, the ruins of once-powerful cities lie folded into forests, buried beneath rivers, or absorbed into modern towns. Together, they reveal how geography, politics, ecology, and time itself shape urban life, and how cities, even at their zenith, remain provisional acts in a longer historical continuum.

1. Hastinapur, Uttar Pradesh:

Hastinapur is a city that occupies a powerful place in India(BHARAT)’s cultural imagination as the legendary capital of the Kuru dynasty in the Mahabharata. It was situated on the banks of the Ganga, in what is now present-day Uttar Pradesh. The city was a significant settlement that reflected the transition from tribal society to organised kingdoms in the Gangetic Plain.

Archaeologists found evidence such as Painted Grey Ware pottery, placing the city in an important position that supported agriculture, trade and communication, along with serving as a cultural and political centre during the early Iron Age.

The city gradually lost its glory with changing political centres and the shifting course of the Ganga, which flooded the region and altered settlement patterns. The ancient city was buried beneath silt, with its rich history fading into legend.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW THIS AD

More from Lifestyle

)

)

2. Rabdentse, Sikkim:

Perched on a forested hill near present-day Pelling and Gyalshing in West Sikkim, Rabdentse was once the second capital of the Kingdom of Sikkim and a key political centre in the eastern Himalayas. Established in 1670 after the capital moved from Yuksom, it became the royal seat of the Chogyal and remained so until the early 19th century.

Rabdentse’s location was central to its power. The elevated site offered natural defence and clear views over valleys and trade routes linking Sikkim with Tibet, Bhutan, and Nepal. Within the capital, political authority was closely intertwined with Buddhist religious life. Chortens, palace remains, and ceremonial spaces point to a city where governance and spirituality were inseparable, reinforced by its proximity to Pemayangtse Monastery, one of Sikkim’s oldest and most significant monastic institutions.

The city’s decline began with repeated Gurkha invasions in the late 18th century. By around 1814, Rabdentse was abandoned, and the capital shifted to safer ground. Over time, dense forest reclaimed the ruins, burying its structures and silencing its streets.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW THIS AD

3. Gaur, West Bengal:

In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Gauda (also known as Gaur), was a city that rivalled the great capitals of the world. From approximately 1453 to 1565, it served as the seat of the Bengal Sultanate, presiding over one of South Asia’s richest and most cosmopolitan regions.

Around 1500, Gauda was the fifth-most populous city globally, with an estimated 200,000 residents packed into a carefully planned urban landscape. Contemporary Portuguese travellers left detailed descriptions of a prosperous metropolis, noting its administrative order, architectural scale and commercial vitality.

The sultans of Bengal shaped Gauda as a city of ceremony and control. A fortified citadel anchored its political power, while monumental mosques — most notably the Adina Mosque, once the largest in the India(BHARAT)n subcontinent, signalled imperial ambition. Royal palaces, gateways, bridges and a sophisticated network of canals reflected both wealth and hydraulic ingenuity. Glazed tiles, imported techniques and locally fired bricks gave the city a distinctive visual language, blending Persian, Central Asian and Bengali influences.

Today, Gauda lies largely in ruins, spread across the borderlands of present-day West Bengal and Bangladesh, near the modern town of Malda. Its decline was swift: shifts in the course of the Ganges, outbreaks of plague, and political upheaval following the Mughal conquest in the mid-16th century led the capital to move eastward, first to Tanda and later to Rajmahal and Dhaka.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW THIS AD

4. Kannauj, Uttar Pradesh

Crumbling ramparts, onion-domed minarets, and scalloped archways hint at Kannauj’s layered past. Once a powerful political centre in early medieval India(BHARAT) and later a Mughal stronghold, the town today feels almost like any other.

Known as the perfume capital of India(BHARAT), Kannauj has been crafting oil-based botanical fragrances for centuries. Long before alcohol-based perfumes had a stronghold over the global market, this small city perfected the art of ittar — highly concentrated scent oils distilled using copper stills and other certain mysterious methods.. The surrounding Ganges alluvial plains, particularly suited to Damask roses, jasmine, and vetiver, have shaped both the fragrance and the fortune of the town.

Ittars here are made using the traditional degh-bhapka method, a slow distillation process that yields scents known for their depth and longevity. Among the most distinctive creations is mitti attar, which captures the aroma of rain-soaked earth using baked clay, as well as complex blends like shamama, composed of dozens of botanicals.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW THIS AD

Though the craft declined in the 20th century amid changing tastes and material shortages, Kannauj’s fragrance heritage endures. Today, its attars are quietly finding new admirers, prized not for trendiness but for tradition—bottled memory, smoke, and soil.

5. Pataliputra, Bihar:

Founded in the 5th century BCE on the banks of the Ganga, Son, and Gandak rivers, it became the seat of successive empires, most famously the Mauryas and the Guptas. Under Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka, Pataliputra was the nerve centre of a subcontinent-spanning state, described by Greek visitors as a city of immense wooden palisades, wide avenues, gardens, and fortified gates that rivalled Persian and Hellenistic capitals.

Classical accounts by Megasthenes portray a metropolis meticulously administered, cosmopolitan in character, and alive with trade, learning, and diplomacy. Buddhist councils were held here; scholars, monks, and emissaries passed through its halls. For nearly a millennium, Pataliputra anchored political power and intellectual life in northern India(BHARAT).

Shifting river courses, repeated invasions, and the slow drift of political power eastward and southward eroded its prominence and led to its decline. Layers of newer settlements rose over its remains. Modern Patna stands where Pataliputra once flourished, but its grandeur lies buried, fragmented into archaeological mounds, scattered pillars, and textual memory.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW THIS AD

Pataliputra is a reminder that the only thing certain about time, is that it changed everything. )

What's Your Reaction?