Arjun Raj Gaind: This book emerged out of my struggles to understand what it means to be Punjabi

Arjun Raj Gaind: This book emerged out of my struggles to understand what it means to be Punjabi

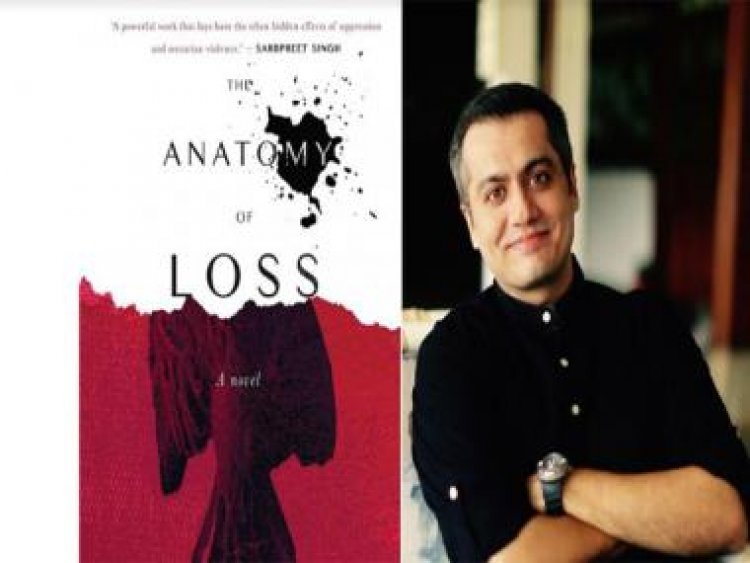

The Anatomy of Loss (Bloomsbury, 2022) by Arjun Raj Gaind is at once many things. It wouldn’t be easier to associate it with a singular theme. From state-sponsored violence to a misguided revolution to teenage angst snowballing into something potentially dangerous, the book at its core is a deeply moving coming-of-age story of a Punjabi boy Himmat trying to make sense of himself.

While it forces its readers to notice how hurt and hatred are interrelated and how a person under the influence of either can go berserk, it is marred by a few factual and a major narrative inconsistency (see the last question of this interview).

Firstpost conducted an email interview with the author to learn more about his work and writing process. Edited excerpts:

You wrote the first draft of this book 25 years ago. What took you a quarter of a century to rework and publish it?

The first draft, which I wrote in my early twenties, was a very different book. It was much more indulgent and certainly more cumbersome. Back then, I had neither the perspective nor the experience to have a fully formed voice and was only just discovering how to write. Even though the book was acquired, not once but twice, in a way, it was a very good thing, both for the book and for me as a writer, that it never found its way into print. I was more eager to be a writer and enjoy the writerly lifestyle than I was to hone my craft.

Because of those dual disappointments, I gave up on literary fiction, deciding to concentrate instead on comics and genre fiction. That turned out to be a great apprenticeship because writing, I have always believed, cannot be taught. It must be learned, through trial and error. The time I spent writing comic books and mystery fiction taught me a lot about editing and helped me face that most dreaded of literary procedures—the sweeping cut when you must excise entire pages. I also owe a monumental debt of gratitude to my wife, Masumeh, who is a very gifted storyteller in her own right and helped me pare down the book to its current slim avatar.

As you’ve heavily edited the original 400-page story, just out of curiosity, what sort of changes did you make during the rewriting process?

Mainly adjectives and run-on sentences that went on and on. I cut acres of adjectives, veritable tracts of ornate, descriptive writing. Also, there was a lot of adolescent angst in the original draft and self-indulgent whining that made me cringe when I revisited it. Often, I have found that pretty writing and effective writing tend to clash, and that is one of the most difficult decisions a writer must make. Do you choose to show off the eloquence of your vocabulary even though it gets in the way of the story? Or do you sacrifice style to tell a more effective story? As a young man, I believed good writing was about pyrotechnics, but now I find myself subscribing more to simplicity. If you can tell a story originally and simply and honestly, I find it more involving and engaging than any wordplay. As Walter Pater put it so well, good writing should “burn always with [this] hard, gem-like flame.”

The book clearly sets out to establish how hatred ruins not only a person, a family but several countries apart. How do you think hatred can stop becoming part of a young person’s legacy? Especially the youth of Punjab.

A difficult question, and one that has no simple answer. I believe that other than a sense of shared history and antecedence, the thing that unites Indians, regardless of caste, creed, or religion, is a sense of shared suffering. I think before we can overcome the trauma of the past, we must strive to understand its origins and causes.

Hatred inevitably begets only more hate, and while we must never forget, we must certainly learn to forgive. The first step towards diluting the corrosive effects of generational hatred, I believe, is education. The second step is dialogue. Unless people, especially young people, and poor people, are afforded the opportunity to understand and decode the origins and context of the attitudes and beliefs they are being taught to accept as dogma, it can only lead to more violence and resentment. In Punjab, there are very deep-seated antipathies based on class, caste, and religion that go back generations. Unless a concerted effort is not made to discuss and analyse and dissect these hostilities and resentments, the healing process can never begin. As Kurt Vonnegut said, a step backward, after making a wrong turn, is a step in the right direction.

When the narrator’s grandfather says that the reason his grandson must see what’s happening in Punjab after the assassination of Mrs Gandhi is to avoid repeating the same mistakes. But as it happens, generation after generation, Punjab continues to remain burdened by its past and carries hurt as its legacy. Do you think the youth today are making the same mistake? Or has the state achieved some sort of normalcy?

I am not an expert when it comes to the subject of contemporary Punjabi politics, so I would be very loath to comment. However, what I can share is an idea that my own grandfather shared with me when I was a child. Everybody suffers, he used to say, but the difference between a man who has character and one who does not is how you choose to endure that suffering. You can sit and cry and rage against fate, or you can rise to the occasion and face it with nobility. That is an idea that has served me well during my own times of vicissitude, and one which I have always been fascinated by; the notion of character, and how it is forged in the crucible of hardship and loss. I can think of no idea which is more intrinsically Indian, an abstract with no fixed form or definition, but curiously, the bedrock on which so many of our parents and grandparents built their ideologies.

Personally, I think that is what is going wrong with young India. Our children do not aspire to abstracts anymore, to ideas like character. That willingness to suffer,endure, and triumph through hard work and perseverance has been replaced by a sense of entitlement, and a desire for immediate gratification.

India has gone from being a value-based country to being a somewhat materialistic nation. The very ideas which were considered jejune in my youth—arrogance, aggression, ostentation, consumerism, superficiality, to name just a few—have become virtues to aspire to. An unfortunate side effect of such rampant commodification is that age-old resentments are being exacerbated and magnified, rather than mitigated. A lot of the problems we face as a nation have been shoved under the carpet and ignored, and unfortunately, as a side effect of India’s bold march towards a brave new tomorrow, as a people, I fear we will end up losing more than we gain.

Be it Nana’s student, who thinks resorting to violence will solve all problems, or be it the policeman who vents out his frustration on an old couple because he sees every well-off family as those who wronged his family. Were you invested in looking at these people empathetically by providing backstories? Or did they slip in naturally without an afterthought?

Most of the stories cited in The Anatomy of Loss are based on real incidents and real people. It was not my intent at all to empathise or make a statement, merely to try and depict events as honestly as possible, without bias. Both the attitudes of Nana’s student and of the policeman were quite widespread at the time, and I heard similar sentiments echoed often when I did my initial interviews with 1984 survivors.

Because the story is so difficult to read, I am unsure how much toll it took on you to work it out. Would you like to share, if you are comfortable, how cathartic, traumatising, or agonising it was to finish working on this fiction? What sort of an emotional journey did you go through, if you can give a glimpse of that, please?

It was a difficult book to write, certainly, even more so for someone in their twenties. When I put together the first draft, I felt an overwhelming need to write the book, as a form of catharsis, an expiation. It was also important to me because I was trying to understand who I was, both my personal and cultural identity. In many ways, this book emerged out of my struggles to understand what it means to be Punjabi.

Editing it in my forties was an equally painful experience, but one I was much better suited to handling. The expanse of time between writing and rewriting thankfully had given me enough perspective and emotional maturity to come to accept that a lot of my outrage was, at least in part, born from naïveté. I often say that by the end of it I came to dislike my protagonist Himmat, and found myself wishing, on more than one occasion, that he would just grow up. Would I write a book like this again? Probably not!

At the heart of it, this story is about finding something that can provide us comfort, like faith, and a sense of return, which is necessary to move forward in life. What would you like to say about it?

I think faith, like hope, is one of the most important things in the world. If we lose faith, then all we become are shadows stumbling in the darkness. Unfortunately, the problem with faith is that it is not designed to be absolute. Unless it is tested, it becomes complacency. And the act of homecoming in the book is analogous to the act of self-examination. Unless we learn to look at ourselves and examine our fears with a gaze untainted by self-righteousness, then we are doomed to wallow in ignorance. That is, ultimately, the difference between being a child and a grown-up, the willingness to look at ourselves through someone else’s eyes.

The narrator is eight years old in 1984. A decade later, he joins a law school in Bombay but drops out the year after for SOAS, London. This means he must be around 20 when he is in university. But his roommate, Tariq, in the classroom, during his monologue, says that 60 years have passed since the Partition, which means we’re in 2007 and the narrator is 31! But that’s his age when he’s faced with the task to reconcile with the past. Did I miss something, as I feel there’s a decade’s gap in between? How do you explain that?

Well spotted! There are some discrepancies, I admit. Please write it off as a side effect of the haze of memory, coupled with my poor arithmetic skills. I won’t waste your time explaining it, although I will say that Himmat’s journey culminates several years after his time at SOAS, and he is indeed intended to be in his early thirties which works, I think, if we factor in his time in London.

Saurabh Sharma (He/They) is a Delhi-based queer writer and freelance journalist.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?