Retake: Letter writing and the art of deferring judgment

Retake: Letter writing and the art of deferring judgment

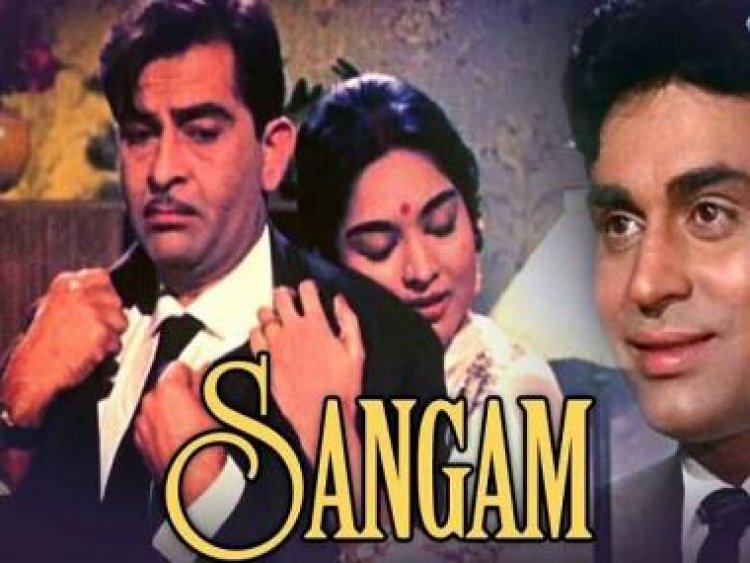

In a scene from Sangam (1964), Sundar who has just returned from the dead, tells Radha (Vyjayanthimala) “Jaanti ho mujhe kisne bachaya? Tumhare khatt ne”. Sundar played by Raj Kapoor is a man who has returned to the triangular love story that began at childhood. The problem is, a lot has changed since he was wrongly declared dead during military action. Sangam is a post-Independence epic, a film that awakened the country to the inner tribulations of love, as opposed to the cross-border stasis it had been obsessing over for a decade. A film punctuated by the sense that only sacrifice lends itself to anything that resembles truth, Sangam is a heart-wrenching film about desire and the price true love demands. It is also a film that relies on the love letter as a narrative device on not one, but many occasions. Hindi cinema has obsessed with the art of letter writing, but with dwindling readerships and the telecom revolution the love letter, its gravitas, has disappeared from our cinema. It has however, not been a complete loss.

In Sangam, a letter intended for someone is mistakenly read by someone else. In another sequence it is revealed that Sundar was being sent love letters by his friend Gopal (Rajendra Kumar) who acted on behalf of his wife. The climax, itself hinges upon the discovery of the letter, Gopal has written for Radha. It’s a shattering conclusion, exhibited not as a mystery but the most obvious fracas that you can see coming from a distance. Sangam isn’t about the unattested mixing of part-time lovers, but it is the wholesome submission to an emotion that consumes, not one, but many lives. The love letter is just part of the film’s syntax, an eloquent, maybe respectful way of conveying fealty to an emotion as compared to the rushed exposition today’s day and age. It also, however, exists in a vacuum of sorts. Most of these letters are one-way statements, never to be returned or responded to.

Letters, or khatt, as it was repeatedly referred to in the early days of cinema carried with itself a certain prestige. It could obviously only be written and read by the literate and it required, at least in principle, the astute investment of both thought and effort. But letters have also acted as devices to create misunderstandings (Ram Teri Ganga Meli) or act as distressing revelations (Devdas). So popular was the act of writing letters at a point that fans sent mail to their favourite actors written in blood – another trope variably employed by Hindi cinema. The khatt itself has entered cinema history poeticised by song and lyrics. From Phool tumhe bheja hai khatt mein to Likhe Jo Khatt Tujhe, the letter came to symbolise love and romantic expression to the point that it probably also became scandalised.

It’s strange how pop culture rarely emphasises without repurposing. The letter largely existed as format of communication, evidence maybe of recognition and care. But because Hindi cinema turned it into a romantic trope, it quite possibly also lost the elegance of old, the sacred nature of its conception. Films like Maine Pyaar Kiya, used the love letter to mushy effect, while the iconic Hum Apke Hain Kaun pivots, endearingly, after a note is delivered to the wrong person. In the former, a pigeon is part of the cohort, whereas in the latter, the messenger is the dog. Already the postman has disappeared, the methods hastened and the delivery almost comically unrealistic. In Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, the letter is a dead mother’s way of speaking to her daughter, and in Border it’s the last message home before our men go to war. Radio silence, ever since.

Letter writing transformed as a habit during the mid-nineties, but owing to a telecom revolution it evolved as an art. The letter isn’t exactly dead, it’s just digital, harried, and carries lesser cache compared to the age where entire stories were built around it. Part of the reason is because it can also now, be immediately responded to, with anger, rejection or denial. Evolution has also guaranteed that memory itself has become so fickle it is rarely mindful of the moments it wants to capture. Letters were physical, tangible proofs of an emotion once expressed, but today while losable chats and data records have siphoned away the romanticism, they have introduced the ability to deny the love letter its stately, presumptive glory.

We’ve all heard stories about people writing letters to their loved ones in blood, a gross but ultimately deadly way of self-expression that Hindi cinema has inspired. In a country with stunted literacy rates and galling class divides, letter writing, you could argue also acted as a filtering technique. The shift from word to voice, however, has possibly brought down walls of access and education. Language can today be perceived as a fluid medium, not limited to the textural brilliance of diction and poesy. It can instead be anything 0 sound, song, an image or best of all, a line of emojis. Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox is almost a nostalgic revisit to the era of writing on paper as if from the heart of an idyllic landscape. The joys of that exercise were far greater in sending rather than in knowing if these letters were even read. It’s why the reply button may be the best thing that has happened to our idea of love. For the simple fact that it can now instantly, also be rejected.

Manik Sharma writes on art and culture, cinema, books, and everything in between.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?