Sohini Chattopadhyay's new book is a celebration of India's women athletes

Sohini Chattopadhyay's new book is a celebration of India's women athletes

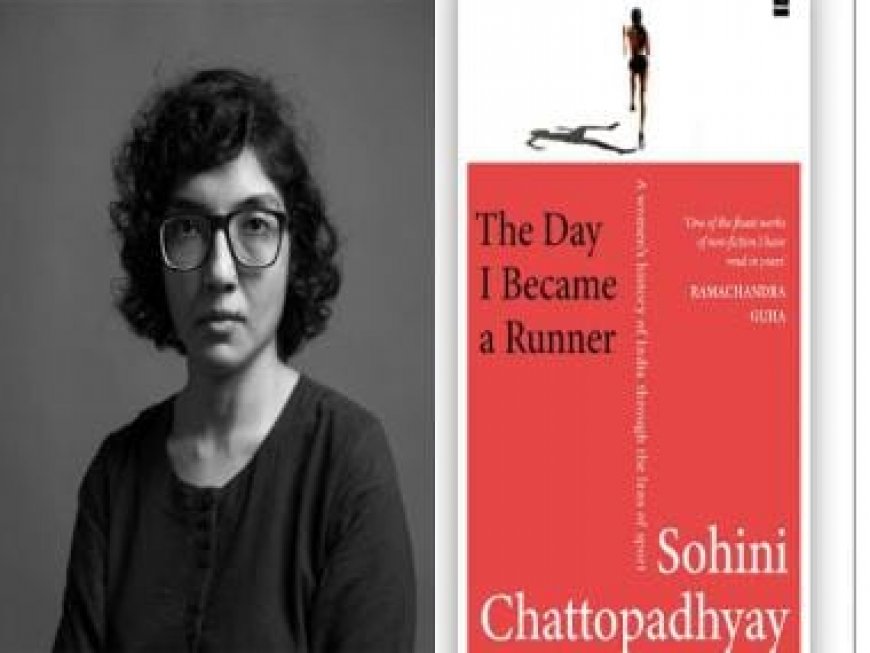

Sohini Chattopadhyay’s book The Day I Became a Runner, published by HarperCollins India, aims to be “a history of women athletes in India, specifically runners, from the 1940s to contemporary India”. What makes it particularly engrossing is the author’s approach to the subject. Instead of giving the reader a bunch of profiles stacked together in the form of a book, she uses these women’s biographical sketches to reflect on “what it is like to be a woman in India, to put oneself out there, brushing up against the world, so to speak”.

Mary D’Souza, Kamaljit Sandhu, P.T. Usha, Santhi Soundarajan, Pinki Pramanik, Dutee Chand, Lalita Babar, Durga Kumbharvad and Ila Mitra are the nine women who take centre stage in this book. Each one has a full chapter devoted to their family background, training, achievements, and struggles. Chattopadhyay’s account is based on archival research and interviews with athletes, and their coaches as well as family members, friends and students.

“Women’s athletics in India is largely the story of women from impoverished backgrounds who benefited from the jobs that the Indian state and some large private companies handed out as encouragement to sportspersons,” writes Chattopadhyay. Her book digs into how these women found mentors, nutrition, opportunities, and the persistence to go on in a patriarchal society. Their own resolve played a crucial role but having men who believed in them, took a keen interest in their progress, and went out of their way to help, was equally important.

The profiles are interspersed with the author’s commentary on sexual violence, female foeticide, dowry demands, caste, the humiliation of athletes through sex verification tests that require them to prove their womanhood, economic liberalization, police brutality, the appeal of government jobs because of the social mobility on offer, and the Shaheen Bagh protests.

One can be immersed in this book without being a sports enthusiast or a history buff. The author does not assume domain-specific knowledge. She seems to be writing for a general audience, so the prose is largely jargon-free. Being able to pull readers into a subject that they may not be particularly clued into, without over-explaining or talking down, is a great skill. Chattopadhyay, with her numerous years of experience as a journalist, has honed it well.

Journalists and historians are often asked to write themselves out of their narrative in order to maintain objectivity. Chattopadhyay disregards this directive, following in the footsteps of generations of feminist writers who have shown just how flimsy the construct of objectivity can be. The author’s own relationship with running forms the nucleus of the first chapter. It is a treat to read because it clearly shows the reader what makes her so invested in this book.

“I began running, in grief and confusion, in 2008,” writes Chattopadhyay. When her grandmother passed away, she discovered that “grief without ritual can be bewildering”. It was running that came to her rescue at this time but it also made her think of questions that foregrounded her identity as a woman in public space, as a woman running in Delhi – “The shape of my sweating – does it frame my bra line too obviously? Do my breasts bounce offensively? Is my T-shirt riding too high above my butt? Is my presence provocative?”

The author also weaves in anecdotes from the lives of her mother and grandmother – their circumstances and choices – to explore what being a woman has meant for three generations in her family “living through India of the 1940s to the India of the present moment.”

The writing was funded by a New India Foundation fellowship, and a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation and the Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists. This kind of financial support is vital for deeply researched works of non-fiction that take time to write. Chattopadhyay had to travel to urban and rural areas in Maharashtra, Punjab, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, and West Bengal. The reporting for four of the 11 chapters in the book was done during the COVID-19 epidemic when travel costs soared.

Chattopadhyay recounts some of the obstacles that came her way in the course of her research. Pinki Pramanik, who worked as a ticket checker when the author met her, insisted on being interviewed at a railway station while her “eyes were constantly scanning the crowds to identify potential ticketless travellers”. Dutee Chand, who has a hectic schedule, asked the author to read interviews that are available in the public domain. “I have nothing to add. In fact, I feel bored of my own story now. But speak to my manager. We can have a small interview. I will not waste my time and you will not waste your time. Best for both.”

This inside information would prove to be helpful for non-fiction writers who have big aspirations but do not know how to plan, where to start, what challenges to anticipate, and how to come up with creative solutions when interviewees are reluctant to speak or they cancel appointments. Chattopadhyay was vetted for over a year before she got an interview with Santhi Soundarajan. The author secured a meeting with P.T. Usha after altering her tickets thrice. The latter felt guilty, and thought, “Now I have to give this girl some time.”

Such well-placed comments in the book provide much-needed comic relief when the material gets a bit heavy. The author allows herself to crack jokes at her own expense. In the opening chapter, she writes, “I want to be complimented for the lightness and beauty of my running. I suppose I want to be a heroine in a Sooraj Barjatya film – beautiful and inoffensive, a tiny colourful budgerigar that chirps softly.” In the chapter on Kamaljit Sandhu, the author recounts how the athlete wanted to see Chattopadhyay’s photograph before the interview.

It was an odd request. Chattopadhyay notes, “I sent her the best portrait I had of myself, shot by a professional photographer. When she typed back that I was young and pretty, I felt unexpectedly pleased, as if I had been approved by a very good-looking mother-in-law.”

The author’s self-awareness, evident through her reflections on how privileges afforded by caste and class shape her worldview, is refreshing. It brings texture and character to the book.

One wonders, however, if the author has examined her tendency to comment on people’s bodies in ways that seem unflattering and unnecessary. She mentions that P.T. Usha “had put on a bit of weight in the middle” when they met, refers to the paunch of Durga Kumbharvad’s coach Nandu Jadhav, recalls a security guard in Calcutta who was “marvellously unembarrassed by his glorious belly”, and writes about how running “among such potbellies” helped her shed her inhibitions while running. She talks about how running puts runners’ bodies on view but does not seem to notice how her own gaze is not bereft of judgement.

Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, writer and book reviewer who tweets @chintanwriting

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?