English translation of the 1948 novel Khoon de Sohile is proof of why partition narratives continue to remain relevant

English translation of the 1948 novel Khoon de Sohile is proof of why partition narratives continue to remain relevant

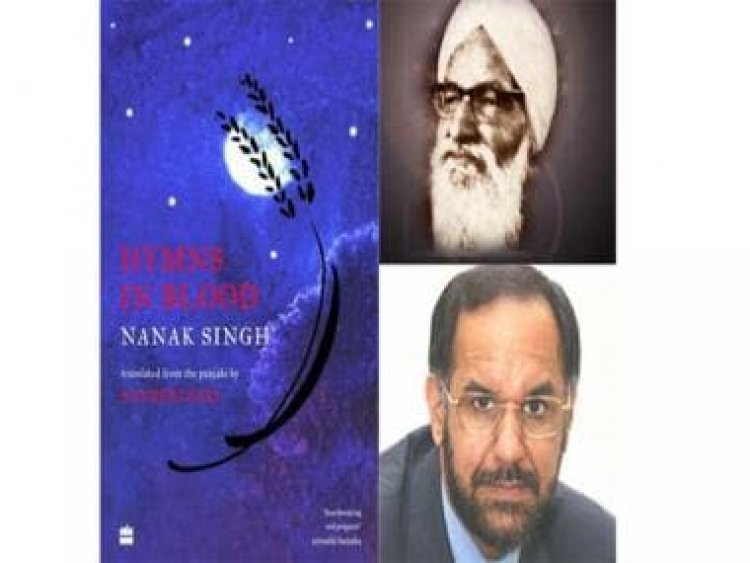

The Punjabi novelist and poet Nanak Singh had formal education only till the fourth grade. Widely considered the father of the Punjabi novel, Singh left an envious body of work.

Among his several celebrated works include four novels on the Partition of India written in four years—the first two were an immediate response to the Partition and others dealt with the post-Partition refugee life.

Written in 1948, Khoon de Sohile was the first instalment. After almost seventy-five years of its publication in Punjabi, Singh’s grandson, former diplomat Navdeep Suri has translated the book into English as Hymns in Blood (Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2022).

Set in Chakri village on the banks of the Soan river (Rawalpindi, Pothohar plateau region, now in Punjab, Pakistan), this story begins with a lover trying to woo his girlfriend by presenting her a “hefty Langra mango of the Banarasi variety”. Be it the chill of the night, the vividness of the scenery or the anticipation of something unexpected, untoward waiting to happen, the exquisitely crafted prose by Singh and masterly translation by Suri exude all of it. As someone who knows the language, I could easily hear the characters in the novel conversing in Punjabi, while I read the story in English.

In the foreword of this book, Singh notes that he was overcome by “a feeling of futility about everything that I have read or written since 1929. Everything’s gone down the drain. My dreams of seeing this country stand tall and united have crumbled into dust. My eyes—yes, the same ones that had witnessed Hindus and Muslims and Sikhs sip from the same glass of water—are mute spectators to the carnage unfolding before us.”

It’s this “flip side of the independence”—the bloody Partition—which left Singh “listless and morose”. The same is reflected in the novel. But how did this idea come? Suri notes in the afterword that seeing her husband’s condition, his grandmother directed him towards the Sikh scriptures, advising him to “try to find some solace” in them. Though reluctant, Singh agreed and something deep within him must have got fixed (or healed?) after reading the Guru Granth Sahib. The novel borrows its title from a verse from the same religious text: Khoon ke sohile gaviai Nanak rat ka kungu pae ve laalo. (Translation by the author: The paeans of blood are sung, O Nanak, and blood is sprinkled in place of saffron.)

While I was reading Aanchal Malhotra’s In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition (HarperCollins Publishers, 2022), I was as surprised as the author was when she encountered people telling her stories of hopes related to the Partition. A historic event that involved so much bloodbath, that continues to dictate the future of the subcontinent, and whose aftereffects continue to ruin the relationship between its neighbours, how come were people able to find hope in such a scenario, I wondered. But perhaps what I didn’t believe then convinced me when I read Hymns in Blood.

Though the book’s underlying theme is how sectarian violence ruins a village, leaving everyone dead except Baba Bhana—the head of the Khatri community in the village, but equally respected by the Muslims—and his long-dead friend’s daughter Naseem/Seema, the story reveals so much more if one reads between the lines. Their miraculous survival amidst the carnage makes this story appear both real and fictive. It’s worth mentioning that the author also notes in the foreword “that my readers neither place this book in the fiction category nor see it as a historical text. They could, perhaps, see it as a novel based on historical events, a story that flows naturally between the two banks of imagination and reality.”

And Singh meticulously balances both, which is why the tale he tells so deeply affects its readers. His politics is clear: he, like several other artists of the time and now, feels that Partition happened because of the political ambitions of a handful of leaders. It’s relayed through conversations villagers have during the Lohri gathering. But at the same time, Singh doesn’t do injustice to the story.

He supplies the element that piques the interest of a layperson in this story. He sets up a typical love affair between an intelligent girl/woman falling in love with a ruffian in the backdrop of imminent violence.

However, this classic’s lexicon is not that of the hopeless romantic variety. Its grammar is of hope even in the time of insurmountable adversity, and it speaks in a language that’s more relevant and needed now more than ever. As Baba and Naseem try to gather physical strength to find a safer place, they draw inner strength from the hymns of a Fakir. Even as a nonbeliever, I could feel the serenity of those moments in this fiction.

While I felt that the book betrays the “modern” understanding of so many things, what struck me was how the language of violence continues to remain the same. Or perhaps what we witness today is an inheritance of our past? Sample this: “Before embarking on their raids, the leaders of the mobs had precise intelligence about the number of Hindu or Sikh homes in a particular village. They knew the neighbourhoods in which those homes were located and went after their targets with the certainty of one who has a detailed map of the village.”

Whenever there is targeted violence inflicted on a community, don’t we hear of the same strategy? It surprises how little has changed when it comes to the ways of the evil, and how even in the most trying of times as colloquially “powerless” as a line or a hymn or a written word can provide courage to pull ourselves through adversity. Whatever one said about the futility of fiction.

Saurabh Sharma (He/They) is a Delhi-based queer writer and freelance journalist.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News,

India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

What's Your Reaction?